These are quotations for the year 2022. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2021, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2022 |

Below are quotations for the year 2022. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

- For 2022, see below.

- 2021

- 2020

- 2019

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

- 2015

- 2014

- 2013

- 2012

- 2011

- 2010

- 2009

- 2008

- 2007

- 2006

- 2005

- 2004

Quotations of the Month for the year 2022

Click on a link to read each quotation

2022

- For Women's Month: Queen Artemisia of Halicarnassus at the Battle of Salamis (Hertodotus Histories Book 8).

- February, 2022: Ancient Populations of Ukraine: the Cimmerians in Homer.

- January, 2022: Ancient Supply-Chain Problems: The Gates of Hercules.

Quotation for March, 2022

For Women's Month: Queen Artemisia of Halicarnassus at the Battle of Salamis |

Above: The Battle of Salamis, illustration by Walter Crane, for Mary Macgregor, The Story of Greece: Told to Boys and Girls, early 20th century, via Wikipedia.Top: Coin of Kaunos, Caria, ca. 470-450 B.C., from the end of the reign of Artemisia and the beginning of the reign of her son, Pisindelis. Obverse: running winged female figure; reverse: sacred baetyl, or meteoric stone. Image from CNG Coins, December 7, 2018, via Wikipedia.

Artemisia of Halicarnassus, woman warrior

For Women's History Month, we celebrate one of the great women warriors of antiquity, Artemisia I of Halicarnassus, who commanded one of the Persian Xerxes' ships at the Battle of Salamis of 480 B.C., in the Second Persian War. In that great sea battle, the Persians were defeated by the remarkable Athenian general Themistocles.

The Persian Wars, as told by Herodotus

Our most complete account of the wars between the Greek states and the Persian Empire comes to us from the Histories of Herodotus (ca. 484 - ca. 425 B.C.), and our Quotation of the Month comes from Book 8 of the Histories.

In 491 B.C., the army of Darius, ruler of the Persian Empire, which was already expanding into Europe, invaded Greece. They were driven back by the Greeks on the plains of Marathon, on the coast northeast of Athens, in a famous battle in 490 B.C. Darius' successor, Xerxes, tried again in 480 B.C., with a bigger invasion force, coming overland through northern Greece, by way of the pass at Thermopylae, a narrow route between mountains and sea. (The name "Thermopylae" means "Hot Gates," from its hot sulphur springs, said to be an entrance to Hades.) A Greek force under King Leonidas of Sparta held off the Persians for a week, until most of the Greeks departed or surrendered, and the remainder, mainly Spartans, died fighting bravely. Simultaneously, a sea battle was being fought off the coast at Artemisium, which ended more or less in a draw.

Themistocles and the "wooden walls"

The Athenian general Themistocles, who had been in command at Artemisium, withdrew his forces to the island of Salamis, off the Athenian coast, and the Persians sacked and burned Athens. The Delphic Oracle had advised the Greeks that "a wooden wall would keep the Athenians safe," and Themistocles cleverly interpreted this to mean the wooden ships of their navy, which was the Athenians' greatest strength.

The Greeks were well organized and all spoke the same language, whereas the Persians had a hodge-podge force from all over their empire, and in the ensuing sea battle off Salamis, the Greeks won a resounding victory. Xerxes left, never to return, but he left a small force under Mardonius, who was defeated by the Greeks in a land battle at Plataea in Boeotia, which ended the Greek dreams of Xerxes forever. Artemisia, who had advised Xerxes not to engage in a naval battle with the Greeks, played an important role in the fight, which she survived.

Artemisia's advice ignored at the definitive Battle of Salamis

Artemisia was the ruler of the port city of Halicarnassus, capital of the region of Caria, now the city of Bodrum in Turkey. She was the daughter of a Cretan mother and and a father from Halicarnassus. She became queen upon the death of her husband, and although at the time of the war she had a grown son, she was still in control.

At Salamis she commanded ships from Halicarnassus, and also ships from Cos, Nisyrus, and Calynda. All were cities that were originally Dorian Greek colonies, but had become part of the Persian Empire. She alone of Xerxes' commanders counseled him not to engage the Greeks in a sea battle, knowing the odds against him, but while he greatly esteemed her, he ignored her advice, following instead the sycophantic opinions of the other leaders.

"My men have become women and my women have become men"

During the battle at Salamis, Artemisia could see that the fight was going badly for Xerxes' disorganized fleet. Pursued by an Athenian trireme and hemmed in by ships of her own fleet, she escaped by ramming a Calyndian ship which stood in her way. The Greeks, recognizing that her ship had sunk a Persian ally, assumed either that hers was a Greek ship or a Persian vessel that had deserted and come over to their side. Xerxes, on the other hand, watching from his seat on the shore, learned that it was Artemisia's ship and, thinking that she had sunk a Greek vessel, praised her valor. Since, as Herodotus tells us in Book 8, paragraph 88, there were no survivors, there was no one to testify against her. Xerxes is said to have uttered the famous words,

"My men have become women and my women have become men."

By now Xerxes was listening to Artemisia's advice. She advised him to leave and go home, "After all, she said, you achieved your objective of burning Athens." He could leave Mardonius to fight on — no big deal if he lost, according to Artemisia! Mardonius stayed, and was defeated by the Greeks at Plataea. Xerxes entrusted his sons, who had accompanied him, to Artemisia to take back to Ephesus. The Athenians, on the other hand, incensed that a woman should take up arms against them, had proclaimed a bounty for Artemisia's capture, and were indignant when they found that she had escaped.

Herodotus himself was a Greek from Halicarnassus, and while Artemisia was on the opposing side in the Persian Wars, he obviously takes pride in this resourceful leader from his home town.

Quotation of the Month, Herodotus 8.88

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Greek and English, the passage in which Xerxes, fooled by Artemisia's bold action, praises her, Herodotus Histories 8.88. The text is that of the Oxford Classical Text, third edition, 1927. The translation is my own.

Herodotus VIII.88

|

Xerxes praises Artemisia's bold tactics |

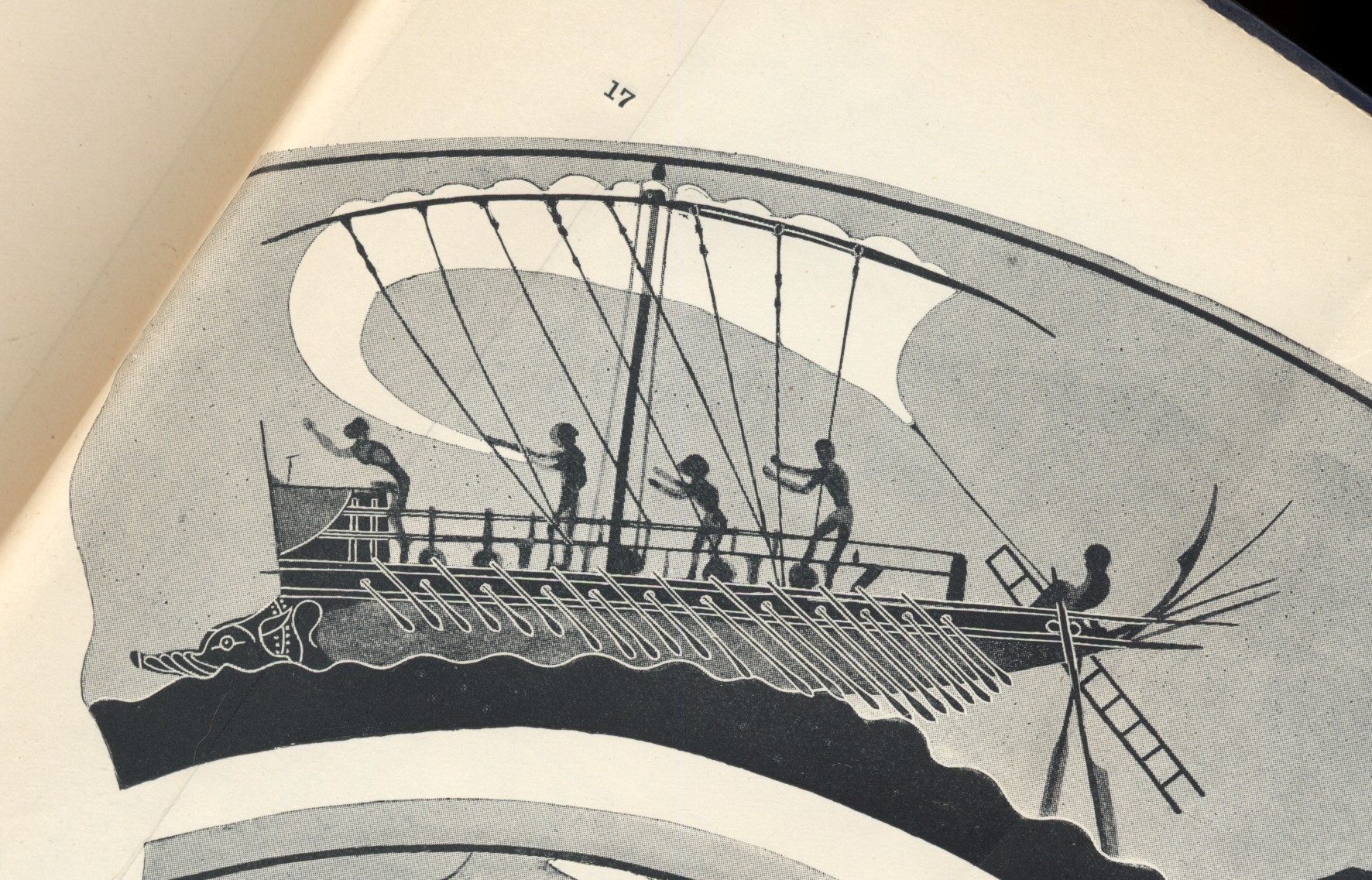

Two war ships in action, about 550 B.C. From a painted vase by Aristonophos found at Caere in Etruria, in the Capitoline Museum in Rome. Copied from Monumenti dell' Instituto, vol. ix, plate 4, in Cecil Torr, Ancient Ships, 1895, Plate 3.

Quotation for February, 2022

Ancient Populations of Ukraine: the Cimmerians in Homer |

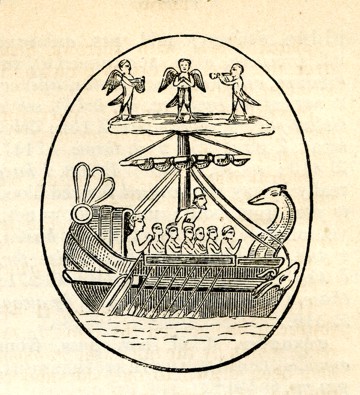

Above: A war ship, about 500 B.C. From a painted vase found at Vulci in Etruria, in the British Museum. Drawing in Cecil Torr, Ancient Ships, 1895, Plate 4 detail.Top: Odysseus' ship, with the Sirens singing to him from the rigging. Illustration from Autenrieth's Homeric Dictionary, 1876. The comment is made: "The cut, from an ancient gem, represents them as bird-footed, an addition of later fable; for Homer, they are beautiful women." The Sirens sang a lovely song to lure sailors to wreck their ships upon the shore. Odysseus stuffed wax in the ears of his crew so that they could not hear the song, then had himself bound to the mast so that he could listen but not escape and be killed.

Fight for domination in Ukraine

The news has been dominated by Russia's invasion of its neighbor, the sovereign state of Ukraine. The Ukrainians have been fighting back heroically to repel what is an unprovoked attack.

Over the millennia, the steppes north of the Black Sea, now home to the country of Ukraine, have seen many great movements of different peoples sweeping across the land, invading, conquering, intermarrying, and settling in its fertile plains. At the archaeological site of Molodova, Ukraine, Paleolithic settlements have been found, dating from perhaps 40,000 B.C., with remains of huts made from mammoth bones, stretched like a frame covered with skins. In Greek and Roman times, the land was inhabited by the Scythians, a nomadic people of perhaps Iranian origin, famed for their gold jewelry, by the Sarmatians, and perhaps by the enigmatic Cimmerians.

The mysterious Cimmerians

Little is known about the Cimmerians, who they were, where they came from. Homer, in the Odyssey (11.13-19) placed them in the dark, foggy, and inhospitable lands on the edge of Ocean, the vast river that flowed all around the disk of Earth. Herodotus, in his Histories (1.15-16) described them as inhabiting the lands north of the Black Sea, from which place they were driven by the Scythians. According to Herodotus, they then went south, where they attacked the Lydians, seizing their capital of Sardis. They were eventually driven out by the Lydians.

Modern scholarship has cast doubt on the usual description of the Cimmerians, in the light of discovery of Assyrian tablets that describe a Cimmerian homeland of Gamir, located near Urartu, to the south of the Caucasus, in the Armenian Highlands. The Cimmerians remain enigmatic, but the legends endure, and Homer's narrative supplies us with our Quotation of the Month.

Odysseus, traveling to the gates of Hades, encounters the Cimmerians beyond the stream of Ocean

In the Odyssey Book 10, the goddess Circe, famous for turning Odysseus' men into pigs, sends Odysseus and his crew on their way (the men having now been returned to their human shape). But first, she tells him, he must go to the realm of Hades, and ask advice of the shade of the great Theban seer Teiresias regarding his journey home. To get to Hades, he must cross the river of Oceanus, where there is a lovely garden of Persephone, but beyond is dark and dank. There he must dig a trench and pour libations, first of milk and honey, then of wine, and finally of water. Then he must sacrifice a ram and a black ewe. The blood will immediately attract the ghosts, but he must not let anyone drink the blood until he has inquired of Teiresias.

Odysseus' journey to the land of Hades in Book 11 is one of the most famous episodes in the Odyssey, but it has been remarked that he never actually enters the Underworld, the ghosts come to him. He follows Circe's directions, sailing to farthest Oceanus, on whose banks is the land and city of the Cimmerians, "wretched mortals" on whom the sun never shines; they live in a land of perpetual mist and cloud. The Sun rises from the Ocean each day, but the Cimmerians seem to live even farther than his place of rising.

Crowds of gibbering ghosts

Odysseus performs his sacrifices, and is immediately surrounded by crowds of gibbering ghosts, all eager to tell their stories, but he holds them all back until he has inquired of Teiresias. From the seer he learns of the Suitors' attempts to marry his wife Penelope and his need to exact vengeance, as well as the future course of his life and eventual peaceful death.

Having learned his fate from Teiresias, Odysseus meets the ghosts of all the famous heroes and heroines, as well as the pathetic shades of ordinary people, many cut down in the prime of life. He meets the ghost of the luckless Elpenor, the youngest of his crew, "neither particularly brave in battle nor very smart," who had drunk too much and fell off the roof as they were preparing to leave. Most poignantly, he meets the ghost of his mother, who had died in his absence. Three times he tried to embrace her, but three times "she flitted from my arms like a shadow or a dream.'

Quotation of the Month, Homer Odyssey 11.1-22

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Greek and English, the beginning of Odysseus' voyage to the land of Hades across the Ocean, where the city of the Cimmerians is located. The text is from the Loeb edition by A.T.Murray, 1919, revised edition 1998. The translation is my own.

Homer Odyssey 11.1-22

|

A voyage to a shadowy landwe first of all dragged the ship into the divine sea waters, and set the mast and sails on the black ship. Taking the sheep we put them on board, and we ourselves embarked, sorrowing and shedding strong tears. Behind our dark-prowed ship, a fair wind that filled our sail, a good companion, was sent by beautiful-haired Circe, dread goddess of human speech. But when we had taken care of all our gear aboard the ship we sat down. The wind and the helmsman kept her on her course. All day long her sail was stretched as she made her way across the sea. The sun set, and all the ways became dark. Our ship arrived at the bounds of deep-flowing Ocean. There is the land and city of the Cimmerians, wrapped in mist and cloud. The radiant sun never looks down on them with his rays, either when he ascends to starry heaven or when he turns back again from heaven to earth, but deadly night stretches over these wretched mortals. Arriving there we beached the ship, and took out the sheep. We ourselves went along beside the stream of Ocean until we came to the place of which Circe had told us. |

An interpretation of the Shield of Achilles as described in Book 18 of the Iliad, ca. 1820, by Angelo Monticelli (1778-1837). Source: "Le Costume Ancien ou Moderne," by Jules Ferrario, via Wikipedia. Note the stream of Ocean, represented in wavy blue around the circumference of the disk.

Quotation for January, 2022

Ancient Supply-Chain Problems: The Gates of Hercules |

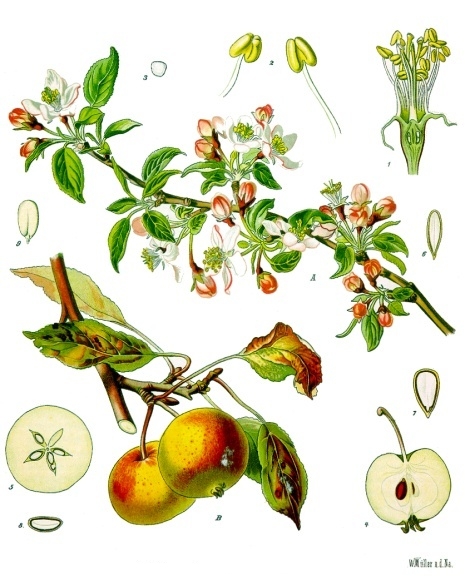

Above: Heracles fighting three-headed Geryon, with Eurytion dying on the ground. Side A from an Attic black-figured amphora, ca. 540 B.C. Musée du Louvre, photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen, 2006, via Wikimedia.Top: Blossoms, fruits, and leaves of the apple tree (Malus domestica). From Franz Eugen Köhler, Köhler's Medizinal-Pflanzen, 1897, via Wikimedia. One of Heracles' Labors was to steal three apples from the Garden of the Hesperides. .

Today's interrupted global supply chain

We have become all too aware, in the past two years, of the concept of the supply chain, the interlinked flow of raw materials, parts for finished products, workers to assemble and transport the products, and the products themselves, that keep us fed, clothed, transported, and entertained. A break in that chain disrupts our lives and can even endanger our lives and our family relationships. One obvious example is the humble microchip, typically imported from China, needed for automobiles, cell phones, medical devices, and a myriad other uses. A disruption in their supply, caused by a shortage of containers and container ships, of dockworkers, truck drivers, and other workers due to the COVID pandemic, has thrown lives into confusion. The same is true of our fruits and vegetables and other produce, which could once be brought to market in days, but now require weeks or month, leading to shortages and price inflation.

We may think of this as a new problem, but it is as old as life on earth, where the products of one species of plant or animal or one tribe of humans becomes the life blood of another.

Ancient supply chains: the Tin Islands and the Port of Cadiz

Amber and tin were two products imported by the ancient Mediterranean civilizations from the farthest reaches of Western Europe. Beads made of amber from the Baltic coast have been found at Troy and in tombs of the Egyptian pharoahs. Tin mixed with copper makes bronze; without it there would be no Bronze Age. It came from the farthest coast of Europe, much of it from Cornwall and Devon on the southeastern tip of England.

The Phoenicians, whose ships sailed back and forth across the Mediterranean, passing beyond what we call the Strait of Gibraltar, mined tin as well as other metals in western Europe. Ingots of tin have been found in ancient Pheonician shipwrecks. The Phoenicians had mines in Spain, but whether they mined British tin is a subject of controversy, as their tin for the most part does not match the type of tin found in Cornwall. The Phoenicians established a post at Gades, the modern Cadiz, off the southwestern coast of Spain, still a flourishing port for both cruise lines and commercial freighters.

Herodotus mentions the amber trade and a place called the Tin Islands (Kassiterides), but doubts their existence, as he did not believe there was any sea on the other side of Europe! (Herodotus Histories 3.115).

The Gates of Hercules: Importing cattle and apples

The narrow entrance to the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean (or the exit from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic), which separates Spain from Morocco, is known today as the Strait of Gibraltar, but was called in antiquity the Pillars of Hercules or the Gates of Hercules. It was the site of two of the Labors of Heracles, imposed on him by King Eurystheus of Tiryns, the theft of the Cattle of Geryon and the taking of apples from the Garden of the Hesperides, both supposed to have happened on the island of Erytheia, which lay beyond the Gates. One version of the story, which, like all myths, had many different versions, had Heracles smashing through a mountain that stood in his way, to create the strait. Not surprisingly, the ancient trade route became mythologized. Cattle and apples, after all, were common commodities, and so we find Heracles importing them, with gods, goddesses, and monsters added to make the story interesting. The location of the island of Erytheia is uncertain, but may have been the sea-encircled ancient port of Cadiz, where Heracles was conflated with the Phoenician god Melqart, to whom there was a temple on the south end of the island.

The three-headed monster Geryon

Geryon is depicted as a monster with three heads and one body, or three heads and three bodies, or three bodies and one head. His fine herd of red cattle was guarded by the two-headed dog Orthus and the herdsman Eurytion. According to genealogies in Hesiod and other sources, Orthus the dog was a cousin once removed of Geryon, and brother of Cerberus, the three-headed hound of the Underworld. Heracles slew Geryon, along with Orthus and Eurytion, and drove the cattle back to Tiryns. The fullest account of the story is found in the Bibliotheke of Pseudo-Apollodorus (first or second century A.D.), but it was told in a poem by the lyric poet Stesichorus (sixth century B.C.) in his poem Geryoneis, which exists today only in fragments. It presented Geryon as a sympathetic character, including a poignant description of his death, "and Geryon bent his neck over to one side, like a poppy that spoils its delicate shapes, shedding its petals all at once" (Denys Page's translation). In a popular version of the story, Heracles trekked across the Libyan desert, but was aided by the Sun God Helios, who lent him transport in the the golden cup in which he usually made his nightly return journey from west to east, to rise anew each day.

The Garden of the Hesperides

Another Labor imposed by Eurystheus finds Heracles back in the lands beyond Ocean, this time to bring back three apples from the orchard belonging to the goddess Hera, which was tended for her by the Hesperides, the "Evening Nymphs." These were, in some versions daughters of the Titan Atlas. The name of one of the Hesperides was Erytheia, the same name given the island that was the home of Geryon. The location of the garden of the Hesperides was sometimes identified as Tartessos, an area of southwestern Spain near Cadiz. Heracles was aided in his theft of the apples by Atlas, who was holding up the celestial sphere, and who tried to trick the hero. Atlas promised to get the apples for Heracles if Heracles would temporarily hold the sphere for him. When Atlas returned with the apples, he offered to take them to Greece for Heracles if Heracles would continue to hold the sphere. Heracles agreed, but said he had first to adjust his cloak. Heracles, of course, did not take back the sphere.

Hesiod's catalog of monsters in the Theogony

Hesiod, in his Theogony, names the Hesperides among the offspring of Night, but fatherless: ". . . the Hesperides, who tend the golden apples beyond storied Ocean, and the trees that bear the fruit" (Theog. 215-216). Geryon is named as part of a catalog of monsters and other prodigies, all descendants of Ceto and Phorcys, both children of Pontus ("Sea") and Gaia ("Earth") (Theog. 270-336). Among these interlinked family members we find several who are connected to Heracles' Labors.

One of the descendants of Ceto and Phorcys was the Gorgon Medusa, When Perseus cut off Medusa's head, there sprang up Pegasus the flying horse, who immediately flew up to the home of the gods, where he brings Zeus's thunder and lightning to him, and Chrysaor ("Golden Sword"). Chrysaor mates with the Oceanid Callirhoe ("Beautifully Flowing") to become the father of Geryon, slain by Heracles. Callirhoe also gives birth to Echidna, half nymph and half snake, who mates with the monster Typhaon and gives birth to Orthus, Geryon's dog, and Cerberus, dog of the Underworld, as well as the Hydra of Lerna, who would also be slain by Heracles as one of his Labors. Echidna (or perhaps Hydra, the pronouns are ambiguous) gives birth to Chimera, part lion, part goat, part snake. Chimera (or perhaps Echidna again) mates with Orthus the dog to produce both the Sphinx and the Nemean Lion, whose slaying was another of Heracles' Labors.

Importing gypsum from Cadiz today

The ancient port of Cadiz, Heracles' mythic Island of Erytheia, still preserves the old trade route, now extending across the Atlantic. Periodically ships can be seen bringing another mineral, gypsum, from Cadiz up the Hudson River, to furnish raw material to a wallboard plant in Montrose, New York. One such vessel is depicted in the photo at the bottom of this article.

Quotation of the Month, Hesiod Theogony vv. 270-294

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Greek and English, part of Hesiod's genealogy of monsters, The text is from the Loeb edition by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, 1914, revised edition 1936. The translation is my own.

Hesiod Theogony 270-294

|

A genealogy of monstersgray from birth, who are called Graiae both by the immortal gods and by men who walk upon the earth, well-dressed Pemphredo and Enyo dressed in saffron, and also the Gorgons, who live beyond the storied Ocean at the edge of Night, where the clear-voiced Hesperides are. They were Sthenno and Euryale and Medusa who suffered a mournful fate. For she was mortal, the others immortal and ageless, both of them. With her lay the Dark-haired One (Poseidon) in a soft meadow among the spring flowers. When Perseus beheaded her, cutting through her neck, out leaped great Chrysaor and the horse Pegasus. The latter was named eponymously, because it was by the springs (pegae) of Ocean that he was born, the former for the golden sword (aor) he held in his hands. Pegasus, flying away and leaving the earth, mother of flocks came to the immortal gods. He lives in the house of Zeus and brings to wise Zeus the thunder and lightning. Chrysaor begot three-headed Geryon, lying in love with Callirhoe, the daughter of the storied Ocean. Mighty Heracles slew Geryon beside his rolling-gaited cattle, in sea-encircled Erytheia, on the day that he drove the wide-browed cattle to holy Tiryns, crossing the ford of Ocean, after also killing Orthus and the cowherd Eurytion in the cloudy farmstead beyond the storied Ocean. |

The bulk cargo ship Spar Apus, owned by the Spar Shipping Company of Norway, photographed on the Hudson River on March 6, 2021. She is low in the water, carrying a heavy load of gypsum from Cadiz, Spain, up the river to a wallboard manufacturing company in Montrose, New York. Photo by C.A. Sowa.

<---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2021 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: