These are quotations for the year 2021. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2021, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2021 |

Below are quotations for the year 2021. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

- For 2021, see below.

- 2020

- 2019

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

- 2015

- 2014

- 2013

- 2012

- 2011

- 2010

- 2009

- 2008

- 2007

- 2006

- 2005

- 2004

Quotations of the Month for the year 2021

Click on a link to read each quotation

2021

- December, 2021: For the Holiday Season of 2021: Lucretius Explains a Tornado.

- November, 2021: For the End of Autumn: Time for Fall Plowing and Planting (Hesiod Works and Days 448-478).

- October, 2021: For Halloween: Horace Apologizes to the Enchantress Canidia (Epode XVII).

- September, 2021: The Anniversary of the Destruction of the World Trade Center Suggests the Destruction of the Temple of Athena by Xerxes: Herodotus Book 8.53.

- August, 2021: A Chorus of Modern Frogs Sugggests Their Ancient Cousins; Aristophanes Frogs 209-249.

- July, 2021: For the Olympic Games 2021: Panhellenic Games at Nemea, Isthmia, Delphi: Pindar Nemean Ode 6.

- June, 2021: Warnings of Disasters That Go Unheeded: Aeschylus Agamemnon 160-183.

- May, 2021: Dolphins' Friendship With Other Species: Homeric Hymn 7 to Dionysos.

- April, 2021: What is Infrastructure? Vitruvius De Architectura.

- March, 2021: For Pi Day, Archimedes of Syracuse: Plutarch, Life of Marcellus.

- February, 2021: For Valentine's Day, a Soldier's Wife Writes to Him: Propertius Elegies 4.3.

- January, 2021: Eagles, Lords of the Skies: Pindar's First Pythian Ode.

Quotation for December, 2021

For the Holiday Season of 2021: Lucretius Explains a Tornado |

Above: Sculptor's conception of Lucretius' appearance, from Wikimedia.

Interrupted holidays

This is the season for fall and winter celebration, with Christmas and New Year's and other festivals around the Winter Solstice. But the expected joy has been interrupted for many. There is the ongoing pandemic of COVID 19, and military conflicts in various parts of the world. We keep those afflicted in our thoughts and prayers. There has also been a series of devastating natural phenomena, wild fires, floods, and deep snow storms. Most surprising and ominous was a late gigantic tornado that swept through parts of the state of Kentucky just before the holidays, wiping out entire towns in its 200-mile path.

Tornados in Greece and Italy

We think of tornados as happening in the mid-Western prairies of the United States, but not in ancient Greece and Rome. But tornados occur in Greece and Italy, and there are mentions of them in our ancient writers. Usually words like vertex and turbo are translated by the less threatening word "whirlwind," so the reference to actual tornadic events is bypassed as a poetic expression.

Two Roman poets who have left us descriptions of what are obviously tornados are Vergil and Lucretius. Vergil, in his First Georgic, describes the effects of destructive winds, including those that sweep across the farmlands in a turbine nigro "a black whirlwind" (Georgic I.321). Vergil is concerned with the loss to the farmer and his crops, and he advises his reader to say prayers to the goddess Ceres. Lucretius' description serves a different purpose. His depiction has the aim of illustrating his scientific theories about the construction of the universe.

Lucretius' scientific explanation of tornados, illustrating his atomic theory

Lucretius (ca. 99-55 B.C.), in his De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) expounds the atomic theories of the Greek Epicurus (341-270 B.C.), which were preceded by those of Leucippus and Democritus (5th cent. B.C.), who held that everything is composed of invisible atoms. Nothing, they say, comes from nothing, but the atoms that make up the universe kept being recycled, even though we cannot see the process.

Just because we cannot see atoms doesn't mean they don't exist. In Book I vv. 265-297, he illustrates this concept by describing the devastating effects of violent winds, including those that whirl around, picking up huge trees and tossing them around. He compares the effect of the wind to the effects of water, when it, too, is swept along, carrying with it mighty boulders as well as strong bridges. We can see the water, but not the wind, yet they act the same.

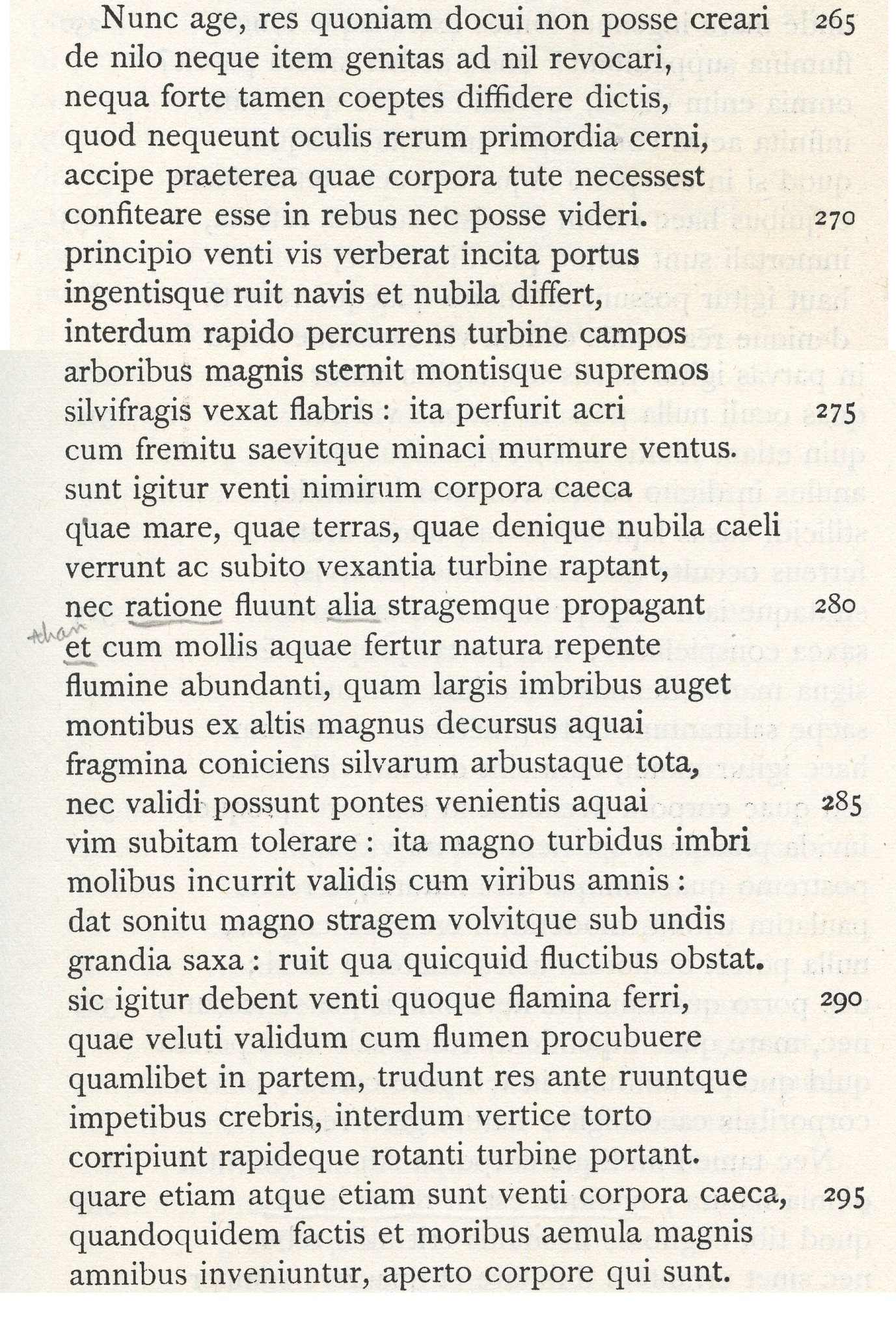

Quotation of the Month, Lucretius De Rerum Natura Book I vv. 265-297

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Latin and English, Lucretius' description of a tornado as illustrating his atomic theory. The text is from the edition by Francis W. Kelsey of 1892. The translation is my own.

Lucretius De Rerum Natura I.265-297

|

You cannot see the wind that creates the swirling vortexfrom nothing, nor, once born, can they be brought back to nothing, so that you may not by chance begin to distrust my words, since the first beginnings of things cannot be discerned by the eye, learn furthermore of bodies which you must confess exist among things, but which cannot be seen. First, there is the might of the wind, which when stirred up strikes the harbors and overwhelms huge ships and scatters the clouds. At times racing through the plains with a tearing whirlwind, it strews them with great trees and shakes the topmost mountains with forest-breaking gusts. Thus the wind shows its fury with its piercing howl and rages with its menacing roar. There are, therefore, doubtlessly unseen bodies of wind which sweep the sea, the lands, and also the clouds in the sky, and shaking them, seizes them up in a whirlwind. Nor do they flow and propagate devastation in any other way than does water, although it is soft, when it is suddenly carried in overwhelming stream, as a great rush of water from the mountain heights swells it with huge amounts of rain, throwing together wreckage of woods and entire trees. Nor can strong bridges withstand the sudden force; so does the river, turbulent with enormous rains, rush against the piers with mighty force; it delivers devastation with great uproar and rolls huge rocks beneath the waves, and sweeps away whatever obstructs its flow. Thus, too, must the blasts of wind be carried, when, like a strong stream they have borne down in some direction, they shove everything before them and sweep it away with frequent attacks, and at times snatch them up in a twisting vortex and carry them off in a whirlwind. Therefore, again and again, there are invisible bodies of wind, since in deeds and habits they are found to be similar to great rivers, which have visible bodies. |

The title page from an edition of the work of Lucretius, Paris, 1570. From the BEIC digital library (Biblioteca Europea di Informazione e Cultura).

Quotation for November, 2021

For the End of Autumn: Time for Fall Plowing and Planting (Hesiod Works and Days 448-478) |

Above: Four-wheeled ox cart in Turtucaia, at the time in Romania, now in Bulgaria. Photo by Kurt Hielscher, 1933, from Wikimedia.Top: Diagram of a plow, according to directions for its construction described by Hesiod in Works and Days 427-436. The farmer would be walking on the left in this diagram, holding onto the echetle or plow-handle. The oxen would be on the right, with the plow-pole attached by the endruon or oaken pin to the yoke of the oxen. Illustration from Leonard Whibley, A Companion to Greek Studies, 3rd ed. 1916, p. 637.

Time to prepare for winter

Fall is a time to prepare for winter, and eventually spring. In urban gardens, bulbs can be planted in fall, which will bloom in spring as daffodils, crocuses, or tulips. In rural areas, wheat can be planted in the fall which will come up in the spring. In places where there are comparatively mild winters, such as the Middle East, spring wheat can be planted in either fall or spring. Where there are severe winters, true hard winter wheat can be planted, which actually requires a period of cold in which it remains in a vegetative state, until it resumes growth in the spring.

Hesiod warns the farmer to get his wagon and plow ready

Hesiod (floruit ca.750 B.C.), in his Works and Days, offers a variety of advice to the farmer on farming techniques, on activities appropriate to each season, and how to live one's personal life. Presented as a poem in heroic hexameters, it is addressed to his brother Perses, depicted as a lazy man who wasted his patrimony.

In Works and Days 448-478, Hesiod gives directions for plowing in the fall, as rainy weather is about to begin. Most imprtantly, get your plow, wagon, oxen and other tools ready in time. The sign for fall plowing is the cry of the migrating crane, who arrives around mid-November.

Don't try to borrow your neighbor's wagon, he needs it himself!

One of Hesiod's themes is self-reliance. The irresponsible man isn't ready in time, and asks his neighbor to provide him with a wagon (an amaxa, a type of four-wheeled cart) and a yoke of oxen. The neighbor, of course, has his own need for cart and oxen, and can't spare them. The lazy man doesn't have time to build his own, not knowing that "there are a humdred timbers in a wagon." (Directions for building a plow were provided in vv. 427-436, see the diagram at the top of this article.) The farmer himself must guide the plow behind his animals. A slave follows, planting seed in the furrows. If the farmer misses the fall planting, he will get another chance in the spring. If he follows these directions, he will live well, and it will be his neighbor, not himself, who must ask for help!

Quotation of the Month, Hesiod Works and Days 448-478

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Greek and English, Hesiod's advice on fall plowing and planting in Works and Days 448-478. The text is from the Loeb edition of 1914, revised edition 1936. The translation is my own.

Hesiod Works and Days 448-478

|

Don't try to borrow a wagon from your neighbor!uttering her yearly cry from the clouds above, she brings a sign of plowing time and indicates the season of rainy winter, but she stings the heart of the ox-less man. Then is the time to feed indoors your curve-horned oxen. For it is easy to say, "Give me a pair of oxen and a four-wheeled cart" and it is just as easy to refuse: "I have work for my oxen." The man who is wealthy in his imagination says his wagon is already built. The fool! He doesn't know that there are a hundred timbers in a wagon, which you should take care to make ready at home. When first the season of plowing is manifest to mortal men, then it is time to get moving, both your slaves and yourself, in dry and wet weather, plowing in the season to plow. Make haste at morning, so that your fields will become full. Plow early in the day; summer fallow will not cheat you. Sow fallow fields when the soil is still light. Fallow fields are a defender from harm and a soother of chldren. Pray to Underground Zeus and pure Demeter that Demeter's holy grain be ripe and heavy, when you first begin plowing, taking the end of the plow handle in your hand and bringing down the goad on the backs of the oxen, as they pull the plow-pole against the yoke straps. A little behind, let a slave holding a mattock make trouble for the birds by hiding the seed. Good management is best for mortal men, bad management is worst. In this way your ears of grain will nod earthward with fullness, if the Olympian god grants you a good result, and you will sweep the cobwebs from your storage containers. I expect you will rejoice as you partake of your stored livelihood, and having plenty you will arrive at gray springtime, nor will you look to others, but another man will have need of your help. |

The famous "Harvester Vase" from Hagia Triada, Crete, Late Minoan, 1600-1450 B.C., now in the Archaeological Museum, Heraklion, Crete. Made of black steatite, it is only about 9 inches high. Only the neck and carved shoulder are original, the bottom part a modern reconstruction of black plaster. A rhyton, a drinking or libation cup, it would have had a small hole in the bottom for pouring liquids. The part we see here depicts a procession, possibly at a harvest festival, of men carrying what may be winnowing fans. Photo by ArchaiOptix, 2019, from Wikimedia.

Quotation for October, 2021

For Halloween: Horace Apologizes to the Enchantress Canidia (Epode XVII) |

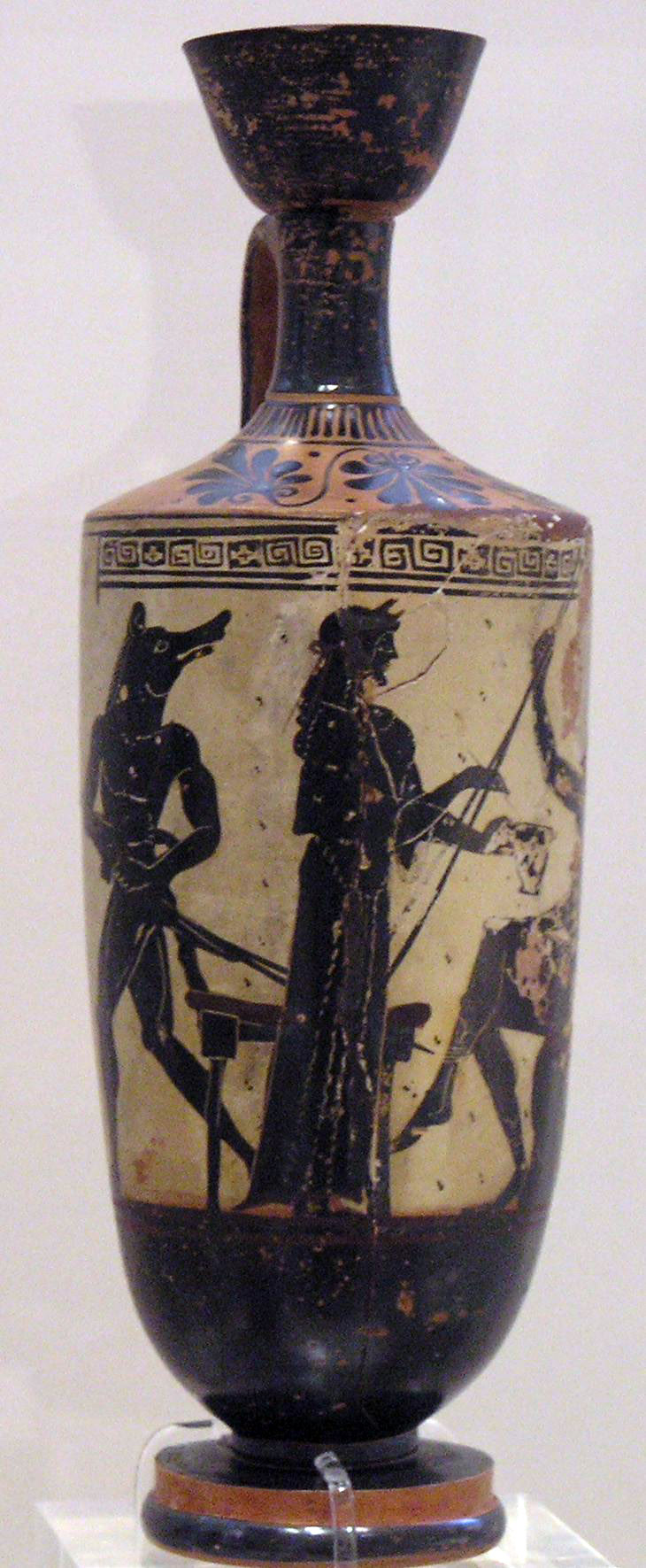

Above: Circe and Ulysses (Odysseus), on a lekythos (oil flask by the Athena Painter, from Eretria, 490-480 B.C., in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. (Photo by Marsyas, image from Wikipedia.)Top: Guy Noir and Cleopatra. Black cats are traditionally associated with Halloween, but these two are quite laid back and relaxed. (Photo by C.A. Sowa, May 2, 2018.)

Halloween, a time for witches and sorcery

Halloween, or All Hallows Eve, is celebrated on the last day of October, and is followed by the Mexican holiday of El Dia de Muertos, or Day of the Dead, which can actually last for several days, even up until November 6 in some localities. Halloween is associated with ghosts and with witches, whose spells and potions were thought to be able to call up the spirits of the dead. During El Dia de Muertos, families honor family members who have died.

The Greeks and Romans were particularly interested in magic, and two of the most famous prototypes of Classical enchantresses were Circe and Medea. We find Circe in the Odyssey, where she turns Odysseus' men into pigs. (See the pictures at the top and bottom of this article.) Medea of Colchis is most famous today for the story of her killing her own children out of revenge for their father, Jason, who had deserted her, after she helped him in his quest for the Golden Fleece, as depicted in Euripides' play Medea. Medea, a descendant of the Sun God Helios, and a niece of Circe, was, however, more than just a wronged woman. She was a powerful enchantress, with a knowledge of spells and magic potions, including those that could make the old young again.

Horace's "Canidia" poems

The Roman poet Horace wrote several poems in which he describes a woman whom he calls "Canidia," supposedly a witch, who uses her powers for malevolent purposes. He describes her in Satires 1.8 and in Epodes 5 and 17. Porphyrius tells us that her real name was Gratidia and that she was a perfumer from Naples, and that Horace had been in love with her, but this may be pure conjecture.

Epode 5 is a particularly gruesome poem, describing how Canidia and her fellow witches bury a young man up to his neck and let him slowly die, so that they can harvest his liver to use in their potions.

Epode 17 is a mock apology, in which Horace "surrenders" to Canidia after she has made him turn from a young man to a decrepit old man, "burning up" and unable to rest or sleep. It is from this Epode that our Quotation of the Month is taken.

Horace's Epode XVII, a recantation

In Epode 17 Horace appeals to Canidia for mercy. He points out that even Circe allowed Odysseus' men to turn from pigs back into men, and refers to several other acts of mercy. In one episode, Telephus, king of the Mysians, wounded by Achilles (whom Horace calls "the grandson of Nereus," since his mother Thetis, was the daughter of the sea god Nereus) was told by the oracle of Apollo that he could only be healed by the rust from Achilles' spear. Achilles graciously assented.

Horace invokes the name of Proserpina (Persephone, queen of the Underworld) and Diana (Artemis, goddess of the moon, whom he identifies with her alter ego Hecate, who is often associated with the dark arts of magic). He now acknowledges what he once denied, namely the powers of the Sabellians (Sabines) and the Mysians, who were known for their magic spells.

Canidia is unmoved. She claims that Horace divulged and made fun of her secret rites, and says that she will make him want to kill himself. She says, "I will ride upon your hated shoulders like a horseman" "vectabor umeris tunc ego inimicis eques).

Quotation of the Month, Horace Epode XVII 1-35

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Latin and English, the opening lines of Horace's Epode XVII. The text is from the Loeb edition of 1929. The translation is my own.

Horace Epode XVII 1-35

|

Canidia, I give up! You have punished me enough!and as a supplicant I pray by the kingdom of Proserpina, and by Diana's inviolable divinity, and also by the books of incantations that have the power to detach the stars and call them down from the sky, Canidia, at last cease your sacred spells and let the magic wheel whirl back, whirl back! Telephus moved to pity the grandson of Nereus against whom he had marshaled the ranks of Mysians and at whom he had hurled his sharp spears. The matrons of Troy anointed the body of man-killer Hector, given over to wild birds and dogs, after the king, leaving the fortified walls, fell, alas! at the feet of headstrong Achilles. The oarsmen of hard-laboring Ulysses put off their limbs bristling with tough hides at the wish of Circe, and their minds and voices returned, and to their faces the familiar dignity. I have paid enough and more than enough penalty to you, you who are beloved of sailors and peddlers. My youth has fled and my modest blushing complexion. My bones are covered with yellow skin, and my hair is white from your fragrances, No leisure releases me from my suffering. Night pushes against day and day upon night, nor can I relieve my strained breast by taking breath. Therefore, I, unfortunate, am forced to believe what I once denied, that Sabine spells can rattle the heart and by Marsian incantations the head will fly apart. What more do you want? O sea and earth, I am burning as neither did Hercules when smeared in the black blood of Nessus, nor the vigorous Sicilian flame in blazing Aetna. But you, until I am dry ashes carried off by noxious winds, are a glowing workshop of Colchian drugs. . . . |

.jpg)

Circe surrounded by Odysseus' crew, whom she has turned into pigs. Painting by Briton Rivière, 1896. (Image from Wikimedia.)

Quotation for September, 2021

The Anniversary of the Destruction of the World Trade Center Suggests the Destruction of the Temple of Athena by Xerxes: Herodotus Book 8.53 |

Above: Statue of Athena, wearing a cape fringed with snakes, from the West Pediment of the Old Temple of Athena on the Acropolis. From Wikimedia, photo December 29, 2014 by Fcgsccac.Top: The Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, when they were young and beautiful.

The anniversary of the fall of the Twin Towers

September 11, 2021 marked the twentieth anniversary of the destruction of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in Manhattan by Middle Eastern terrorists. A total of 2,763 persons are known to have died when hijackers flew two planes into the towers, leading to their collapse. These included those working in the buildings and the firemen and other first responders attempting to save the occupants.

The Towers were a true work of living sculpture. Their construction was unique. Lacking the steel skeleton common to modern skyscrapers, the towers designed by Minoru Yamasaki were supported by an exoskeleton of steel grillwork, in order to maximize floor space on each story. The vertical edges of the buildings, instead of being squared off, were beveled, and contrasting bands one and two thirds of the way up relieved their stark verticality. Moreover, the two structures were offset from each other, so that they changed aspect when seen from various directions and at different times of day.

The World Trade Center as a sacred place

In their short life (1970-2001) the Twin Towers were iconic in every sense. The site is now called a "sacred space" because of the great loss of life, but, as I describe in an essay written at the time, The World Trade Center as a sacred place, the place was always sacred. Lower Manhattan was the sacred land of the Lenape Indians, who made their community and buried their dead there. The Towers, reaching for the sky like a giant tuning fork, were a symbol of aspiration known all over the world, greeting the immigrant like the Statue of Liberty, a symbol of New York and of American possibility. The terrorists knew this. The site is not sacred because it and its inhabitants were destroyed, it was destroyed because it was sacred.

This month's Quotation of the Month describes the destruction of another sacred structure, the Old Temple of Athena on the Acropolis of Athens in 480 B.C. by the Persians. Unlike the Twin Towers, which were never rebuilt (the footprints of the Towers are now occupied by a pair of reflecting pools), the temple of Athena was rebuilt. The rebuilt structure is the one we know as the Parthenon, which itself has a long and varied history.

The destruction of the Old Temple of Athena on the Acropolis

We tend to think of the Parthenon, the iconic symbol of Athens and indeed of the ancient world, as always having been there, dominating the city as it sits on the Acropolis mesa. It seems frozen in time, and even the addition of a disabled-accessible walkway is criticized for disturbing the sanctity of the place. But it was only one in a series of temples built on the site to honor Athena Polias, "Athena Protector of the City," and even in more modern times, it was rebuilt and refashioned to suit the needs of various occupiers of the city.

The Acropolis was always a place of power and meaning. Parts of a Mycenaean fortification wall of the 13th century B.C. survive, on a site that had been inhabited since Neolithic times. The first structure that we could call a predecessor of the Parthenon was the Hekatompedon, or "Hundred-footer," built around 570-550 B.C. It was demolished by the Athenians after the defeat of the Persians at the Battle of Marathon in the First Persian War in 490 B.C. so that a larger temple, known as the Older Parthenon, could be constructed. This Older Parthenon or Pre-Parthenon was still under construction when the returning Persians, under Xerxes, destroyed the temple and other structures and massacred those seeking shelter there.

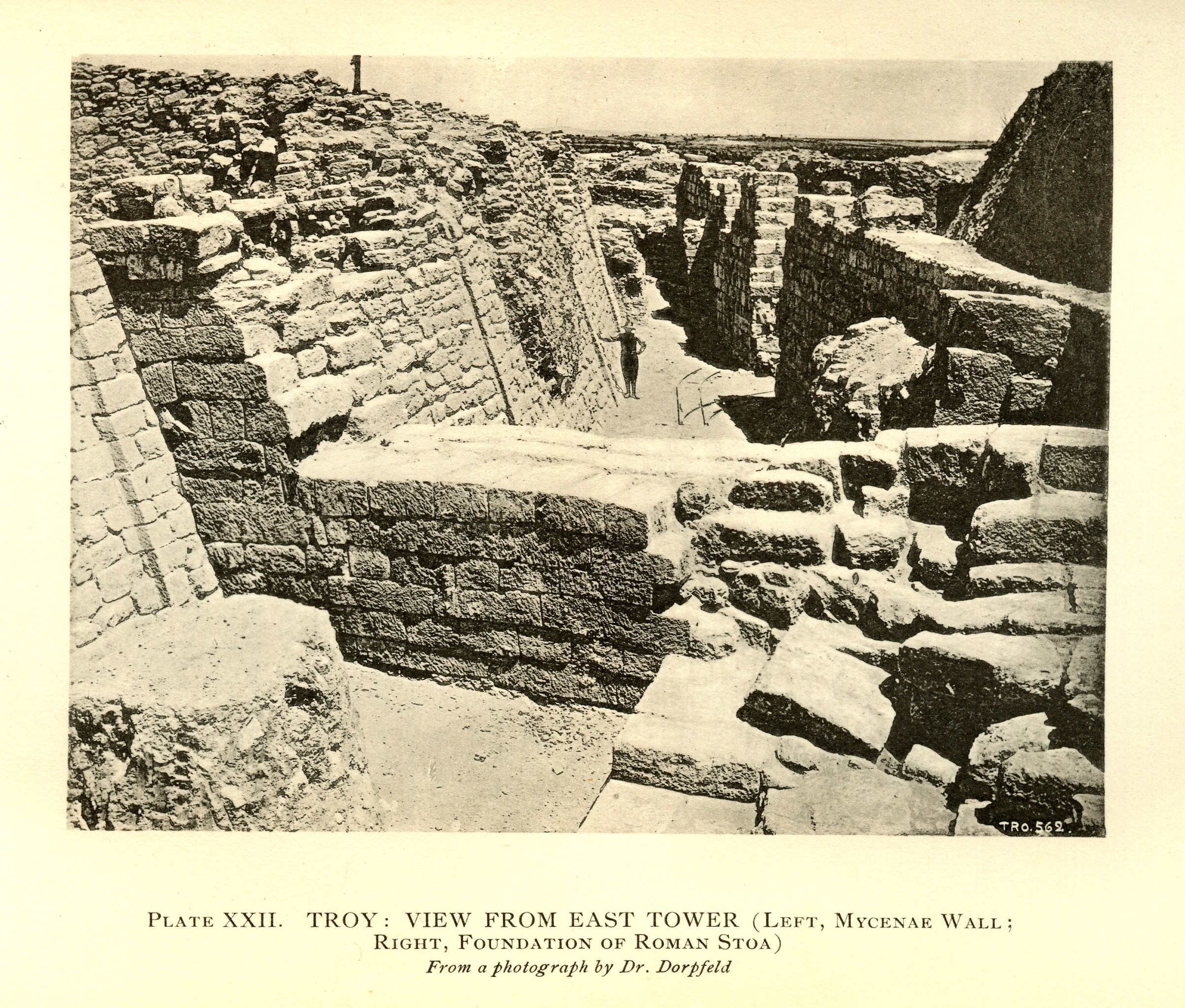

Dörpfeld's discoveries on the Acropolis, and the Parthenon rebuilt

In 1885, Wilhelm Dörpfeld discovered foundations believed to be those of the Old Athena Temple, next to the Erechtheion, a temple famous for its porch of the caryatids, female statues holding up the roof instead of columns. A picture of these foundations appears at the foot of this article. Sculpture from this old temple has been found, including the statue of Athena shown at the head of the article.

The present Parthenon was built near the site of the old temple, at the height of the Athenian Empire under Pericles, as a temple and as a treasury. In the sixth century A.D., it was converted into a Christian church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. After the Ottoman conquest in the 15th century, it was turned into a mosque. In 1687, a Venetian bombardment caused an ammunition dump stored in the building to explode, reducing it to the splendid ruin that we see today.

Herodotus and Themistocles' "wooden walls"

Herodotus, in Book 8 of his Histories, describes how the Persians discovered an unguarded way up the rocky outcrop, thought to be impregnable. An oracle had told the Athenians to seek shelter behind the "wooden walls," and some said that this meant a wooden palisade (although the oracle also said that all of mainland Greece would fall to the Persians). However, Themistocles, a great promoter of the Athenian navy, cleverly interpreted the oracle to mean that the Athenians should rely upon their wooden ships. Themistocles led the Athenians to defeat the Persians at the Sea Battle of Salamis, and the invading army finally met defeat at the land battle of Plataea and a further sea battle at Mycale.

A clash of powers with many sides

To our modern eyes, considering the wary relationship between Western powers and those of the Middle East, we often see the Persian Wars as a battle between "Good" (Greeks) and "Bad" (Persians). But the relationship was more complicated than that. Not every Greek city was hostile to the Persians. Several cities, including Argos and Thebes, were sympathetic to the Persians. Themistocles himself, embroiled in later life in Athenian politics, went into exile and lived out his life as governor of Magnesia under the Persian king Artaxerxes I. Herodotus, Greek historian of the Persian conflict, was born in Halicarnassus in Asia Minor, then part of the Persian Empire, and was accused by Plutarch of being too sympathetic to the Persian side. And Aeschylus, one of the greatest Athenian dramatists, who had himself fought in the Persian War, perhaps at Salamis, created his tragedy The Persians as a picture of the ill-fated invasion by Xerxes from the Persian point of view.

Quotation of the Month, Herodotus Histories 8.53

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Greek and English, Herodotus' account of the sacking of the Acropolis by the Persians. The Oxford text has been used, third edition, 1927. The translation is my own.

Herodotus Histories 8.53

|

The Persian forces find a secret way onto the Acropolis |

The foundations of the Old Athena Temple, next to the Erchtheion. From Martin Luther D'Ooge, The Acropolis of Athens, 1909.

Quotation for August, 2021

A Chorus of Modern Frogs Sugggests Their Ancient Cousins; Dionysos Contends With their Cacophony in Aristophanes Frogs |

Above: Bacchanalian procession, in a red-figured vase painting. From a lithograph, ca. 1840, in my collection.Top: A frog riding on a horse. Cartoon by Christine Cooper Angier (my mother), 1950's.

Frogs in my garden

Brekekekex koax koax!

Throughout August, a night chorus of tree frogs has carried on a constant conversation. And they are LOUD. They drown out almost everything else. (Although now the crickets are starting to mount a countersong.)

A chorus of frogs, did you say? There is only one possible Quotation of the Month, and that is the frog chorus from Aristophanes' Frogs, who annoy Dionysos so much on his journey to the Underworld.

Athens in a time of exhaustion needed a lift

Aristophanes' play The Frogs (Greek: Batrachoi) won first prize at the Lenaia, one of the festivals of Dionysos, in January 405 B.C. It was a time of disillusionment and exhaustion at Athens. The Peloponnesian War, which had been going on for more than thirty years, was dragging to its conclusion (in which the Spartans would ultimately prevail). The Athenian fleet had just won the naval battle of Arginusae, but a bitter taste was left by the prosecution of the generals in charge, for neglecting to save sailors on the floating wrecks. A few years before, in 411 B.C., democracy itself was temporarily overturned by the oligarchic party of The 400. The great political leaders of an earlier time were gone, men like Pericles, dead of the great plague of 430-429 B.C., which itself had sapped the morale of the Athenian people.

The great Athenian dramatists were also gone. Aeschylus, whose grand plays like the Oresteia trilogy make him the father of classical Athenian tragedy, had died fifty years before, in 456 B.C. Euripides, who had introduced a quality of emotion and human feelings into plays like The Trojan Women, had died just recently, in 406 B.C. (Sophocles, the third great master of tragedy, would die during the preparation of The Frogs for production.) Where could the Athenians look for inspiration and moral courage?

Dionysos visits the Underworld so that he can bring back Euripides

The god Dionysos, having fallen totally in love with Euripides and his plays, decides to go to the Underworld to bring back his beloved playwright. He and his slave Xanthias first visit his half-brother, the hero Heracles, to ask his advice on the best way to get to the realm of Hades, since Heracles went there himself to bring back the three-headed dog Cerberus. Heracles first suggests various ways of committing suicide, but then tells them a better if more difficult way. So then we see Dionysos, improbably dressed as Heracles, and Xanthias, on the shore of a lake. There they hire Charon, who is ferrying a corpse, to take them across. They also make a deal with the corpse to carry their baggage. Charon, however, will not take the slave, Xanthias, who has to walk around the lake. He will only take Dionysos, who has to help row the boat, unathletic as he is, despite the Heracles getup.

A chorus of spirit frogs

It is on the Acherusian Lake that we encounter the Frogs who give the play its name. Charon assures Dionysos that he will hear "the loveliest songs" — of "frog-swans." Dionysos gets a rude shock, hearing the very loud croaking of assertive amphibians. The frogs are actually ghosts of frogs who died, who formerly inhabited the reedy marshlands. They sing, er, croak nostalgically about their old lives. Just as Odysseus saw Orion, the great hunter, still vigorously hunting game in the afterlife, so the frogs still dive among the water plants and sing their loud "Brekekex koax koax!" But it infuriates Dionysos, who is already suffering from blisters on his hands and backside from rowing. If he leans too far forward, he says, his arse will soon yell "Brekekekex koax koax!"

Finally Dionysos and Xanthias get to the other side, and we see no more of the frogs. Dionysos encounters the main chorus of the play, made up of Eleusinian initiates, who also pursue their rites in the Underworld. Meanwhile, a contest has broken out between the two deceased dramatists Aeschylus and Euripides, as to whose plays are better. The winner will be invited to sit at Pluto's side at dinner in the assembly hall. (Sophocles, recently died, politely defers to Aeschylus.) Aeacus, one of the three mythic judges in the Underworld (the others are Rhadamanthus and Minos) decrees that they will bring out a set of scales, in which the "weightiness" of each contestant's poetry will be determined. Dionysos, as god of drama, will be the judge.

Surprise! Aeschylus wins the contest against Euripides

Aeschylus and Euripides takes turns reciting lines from their dramas, often interrupting each other with silly remarks and criticisms of each others' styles. Dionysus is asked to make his choice, and he gives his opinion that the poet chosen to return to the land of the living should not only be the best dramatist, but the man who can best advise the city on political and moral questions which trouble it. Finally he says "This is my decision; I shall choose the one my soul delights in" but when Euripides reminds him of his oath to take him, not Aeschylus, home with him, Dionysos replies "It was my tongue that swore — but I choose Aeschylus!" (vv. 1466-1471). This line parodies a famous quote from Euripides' Hippolytus in which Hippolytus has sworn not to tell his father Theseus of his stepmother Phaedra's illicit love for him "My tongue swore, not my mind."

Aeschylus, by Dionysus' choice, will return to the land of the living for a time, in order to save Athens by his noble counsel. He, in turn, chooses Sophocles, not Euripides, to hold his place in Hades while he is gone.

This final scene, like the entire play, is full of political and topical comedy bits that would instantly strike a chord in Aristophanes' Athenian audience.

Quotation of the Month, Arisophanes' Frogs vv. 209-249

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Greek and English, the opening verses of the Frogs' chorus. The text is from the Loeb edition of 1924. The translation is my own.

Brekekekex koax koax!

Aristophanes Frogs 209-249

|

The frogs describe their bubbly song-filled lifeFROGS: Brekekekex koax koax, DIONYSOS: Well, I am beginning to feel sore FROGS: Brekekekex koax koax. DIONYSOS: May you and your "koax" perish. FROGS: Well said, busybody. DIONYSOS: Well I have blisters FROGS: Rather, then, |

One of our tree frogs, who somehow got into our upstairs hallway. It may have hatched over the winter in one of our flowerpots. I caught it in a jar, photographed it, and released it into the garden. (Photograph by C.A. Sowa, Feb. 24, 2016.)

Quotation for July, 2021

For the Olympic Games 2021: Panhellenic Games at Nemea, Isthmia, Delphi: Pindar Nemean Ode 6 |

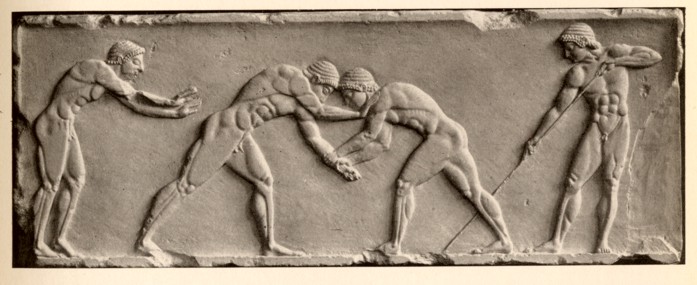

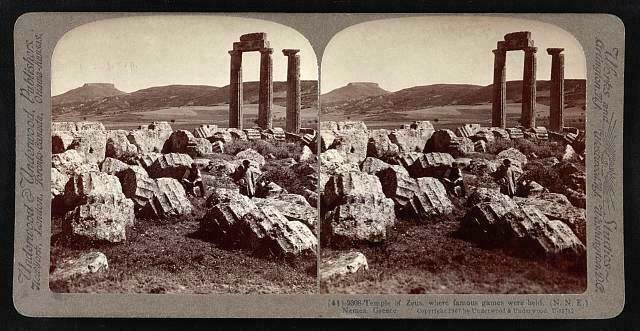

Above: Temple of Zeus, Nemea, in an old stereo view, 1907.Top: Wrestlers, depicted on one side of the base of a funerary kouros, built into the Themistoklean wall, ca. 510-500 B.C. National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

Olympics in an off year

The Olympic Games are in full swing in Tokyo, Japan. They were supposed to be held in the year 2020, but because of the Covid pandemic were postponed until 2021. Unlike the ancient Olympics, which were held only in Olympia, a town on the banks of the Alpheus River in southern Greece, on the peninsula of the Peloponnese, the modern Olympics move from one location to another around the world.

This, however, tells only part of the story, as the Olympics were not the only major sports festivals held in ancient Greece. The Panhellenic Games, that is, contests open to participants from all over the Greek world, were held every year in one or another of a set of different locations, on a rotating basis. These were, in addition to the Olympics, the Nemean, Isthmian, and Pythian Games.

Panhellenic Games in a rotating circuit

The Olympic Games were the oldest, founded, as tradition has it, in 776 B.C. They were held in honor of Zeus every four years, and the four year period between games, called the Olympiad, was an important means of dating events. The year of the Olympic Games was considered year one of an Olympiad.

The Nemean Games, played at Nemea, near Corinth (also in southern Greece) in honor of Zeus and Heracles, and the Isthmian Games, played in honor of Poseidon at his temple at the Isthmus of Corinth, were played twice as often as the Olympics, being held in the second and fourth years of an Olympiad (but at different times of year). The Pythian Games, held on the rocky mountain ledges of Delphi (also called Pytho) northwest of Athens in the third year of every Olympiad, was the only event not held in southern Greece. All three of these games were probably founded in the 6th century B.C.

The main events at all the games were chariot racing, wrestling, boxing, pankration, stadion, and pentathlon. The stadion, a foot race, was the oldest and most prestigious event. The pankration or "all strengths" was a combination of boxing, wrestling, kicking, etc. with few rules, similar to today's mixed martial arts. The pentathlon consisted of wrestling, stadion, long jump, javelin throw, and discus throw. The prize in all of the games was a leafy wreath, for the Olympics an olive wreath, for the Pythian, one of laurel, for the Isthmian, one of pine, and for the Nemean the wreath was of wild celery.

There were also music and dance performances, with victory odes composed by poets like the great Theban lyric poet Pindar, whose Nemean Ode 6 provides our Quotation of the Month.

The site of Nemea

Because the 2020 Olympics were postponed until 2021, we shall exercise some poetic license in assuming that since we are in the second year of an Olympiad, we are now celebrating the Nemean Games!

The site of Nemea has been known for centuries, recognized for the starkly dramatic columns of the Temple of Zeus standing amid a ruin of fallen column drums in the hilly plain south of Corinth, as seen in the antique stereo view at the top of this essay. Nemea was said in legend to be the home of the Nemean Lion, the terrible monster defeated by Heracles as one of his Twelve Labors.

The earliest excavations at Nemea were made briefly in 1766 by the society of the Dilettanti of London, and the French did some excavating in 1884 and 1912. Serious work at the site began in 1924-1926 by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and the University of Cincinnati under Bert Hodge Hill and Carl W. Blegen. Among their discoveries was the location of the ancient Stadium (from whose measurements the dsignation of the ancient stadion foot race is derived). In 1962 Charles K. Williams of the American School of Classical Studies began a process of publication of the Temple of Zeus, and in 1964 restarted what was described at the time as "cleanup excavation" of the entire site. The most thorough excavation and study of the site has been done from 1973-1986 by a group from the University of California at Berkeley under the aegis of the American School of Classical Studies, led by Dr. Stephen G. Miller, who has also helped revive a modern version of the Nemean Games.

Some personal recollections of Nemea

I myself played a small part in the 1964 excavations at Nemea. I was a student at the American School of Classical Studies in 1963-1964, and had hoped to join in an excavation in the spring semester. It was my bad luck that there was no excavating being done that year at Corinth, where the ASCS has been excavating, so I got a job archiving the objects in the School's little museum at Corinth. Then the campaign at Nemea arose, but the glass ceiling was firmly in place, and Charles Williams told me that girls were not welcome on his excavation! But in my persona as archivist I was able to wangle a few days' visit to the site, with the purpose of identifying a group of old photos from Blegen's 1926 excavations. When the site was abandoned, all the trenches had been filled in, and there was no way of telling where unlabeled photos had been taken. However, by matching up existing trees, columns, hills, and anything else that appeared in the pictures, I was able to identify the locations of most, if not all of the photos. And I at least got to hang around the excavation for a few days.

Pindar's Nemean 6

Pindar's Sixth Nemean Ode was composed in honor of Alcidamas of Aegina, winner of the boys' wrestling contest, possibly in 463 B.C. Pindar would have composed not only the words, but the music and also the choreography of the performance.

The ode begins with a famously ambiguous statement: "One is the race of men, one the race of gods; both take their breath from the same mother." The "mother" is unquestionably Gaia, "Earth," but is Pindar saying that men and gods are the same race, or that they are separate? Arguments have been made on both sides, but grammatical evidence seems to point to identity, rather than diversity. Despite their likeness, men and gods differ in the course of their lives, for the gods live eternally in heaven. Yet there are similarities, although humans can never know what their fate portends. Pindar goes on to compare the family of Alcidamas to a farmer's field, which alternates between years of fruitfulness and years of fallow while it recovers its strength. Alcidamas' father won no prizes in any of the Games, but his grandfather won contests in the Olympian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games. Likewise, Alcidamas' great-grandfather was unsuccessful, but his three brothers were winners. The rest of the poem goes on to describe the successes of various members of the family, descendants of the famous clan of the Bassidae. Although any Greek could take part in the Games, only the aristocratic or the wealthy had the resources for the training, not to mention the ability to travel, required to take part in these festivals.

Quotation of the Month, Pindar Nemean 6 vv. 1-15

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Greek and English, the opening stanzas of Pindar's Sixth Nemean Ode. The text is from the Oxford edition of 1935 (reprinted 1958), edited by C.M. Bowra. The translation is my own.

Pindar Nemean 6 1-15

|

A grandson repeats his grandfather's exploits:FOR ALKIDAMAS OF AEGINA, BOY WRESTLER One is the race of men, |

Hercules wrestling the Nemean Lion, detail of a mosaic depicting the Twelve Labors of Hercules, Roman, from Lliria (Valencia), Spain, between 201-250 A.D. Museo Arqueológico Madrid, Photo by Luis Garcia, March 12, 2006, via Wikimedia.

Quotation for June, 2021

Warnings of Disasters That Go Unheeded: Aeschylus Agamemnon 160-183 |

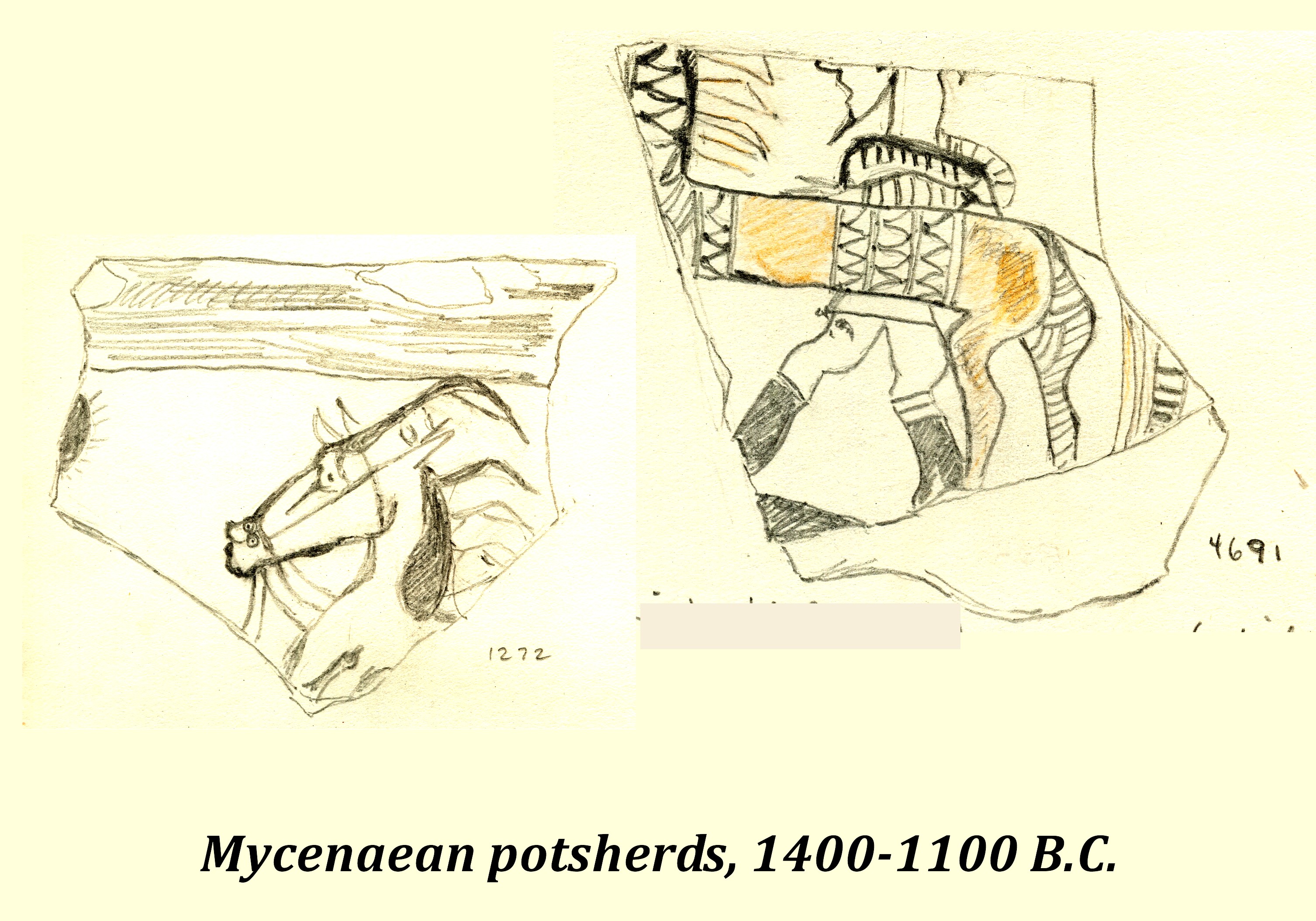

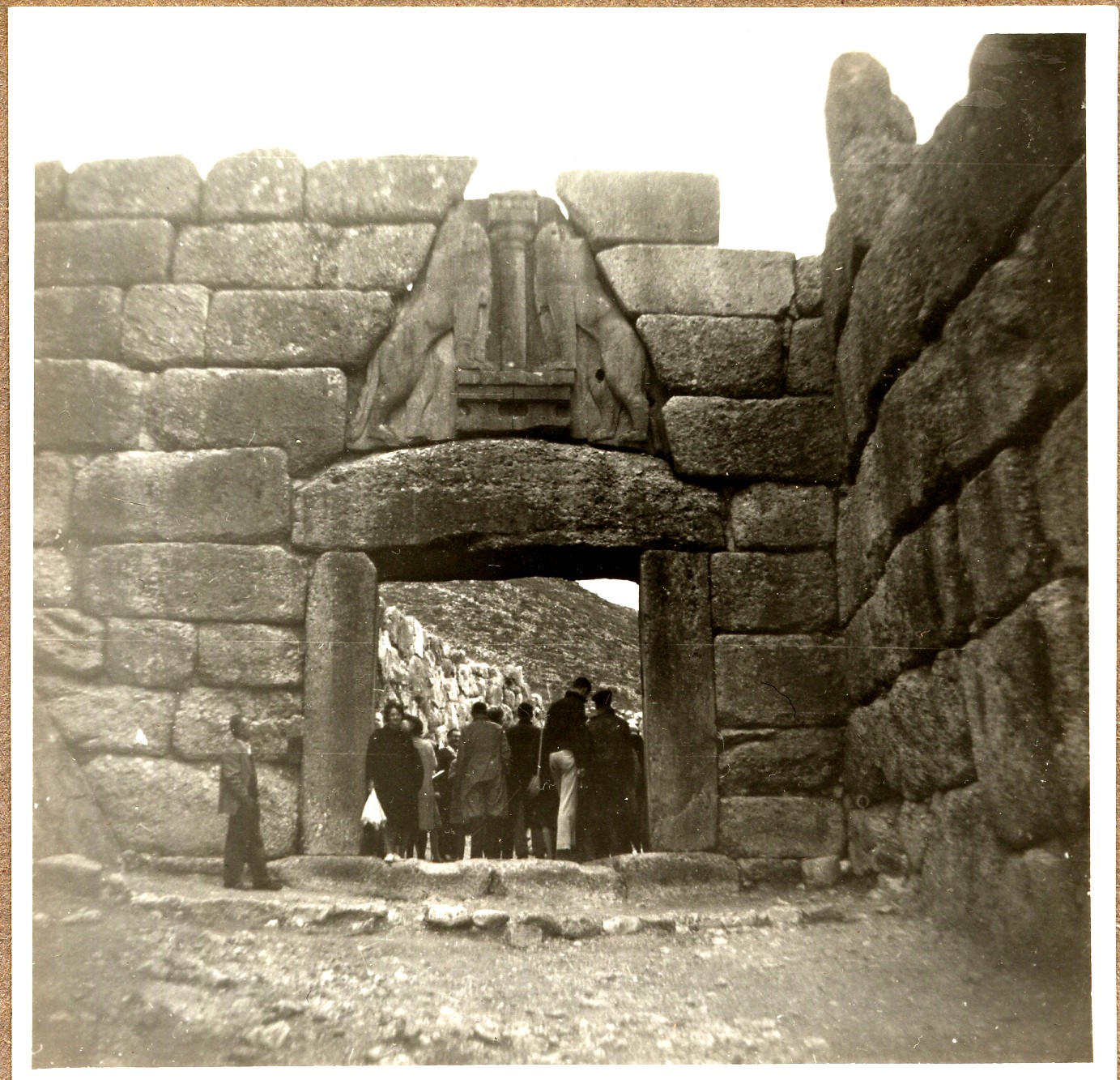

Above: The Lion Gate at Mycenae, with students and faculty from the American School of Classical Studies entering, 1964. I, in my student days, am standing against the left side of the doorway holding an unbrella, in a photo taken by Fr. Edward Bodnar, using my camera. It is from this location that King Agamemnon would have gone forth to fight the Trojans, and where, following the war, he would enter, only to be murdered by his wife Clytemnestra, having ignored the warnings of Cassandra. The lions' heads, which were carved separately, are unfortunately gone.Top: Mycenaean potsherds, depicting a horse and a man with his horse, 1400-1100 B.C., Athens, National Museum. From drawings that I made in 1964.

Disasters strike when warnings are ignored

The news is dominated by two tragedies that could have been averted, the global COVID pandemic and, in the past week, the collapse of the Champlain Towers condominium in Surfside, Florida. In both cases, warnings were ignored which could have prevented devastation. In the case of the pandemic, scientists and physicians had warned for years that a disease of some kind could sweep over the world, taking millions of lives, and that medical and social preparations should be planned for. It was a hundred years since the influenza epidemic of 1918-20, but there were more recent episodes, including the AIDS crisis, Ebola, and the swine flu. Yet funding was cut for basic medical research, and even after cases appeared, politicians and conspiracy theorists downplayed the threat, and derided science in general.

In the case of the building collapse, engineers had warned at least since 2018 of safety deficiencies in the structure. Here, too, warnings were dismissed as insignificant.

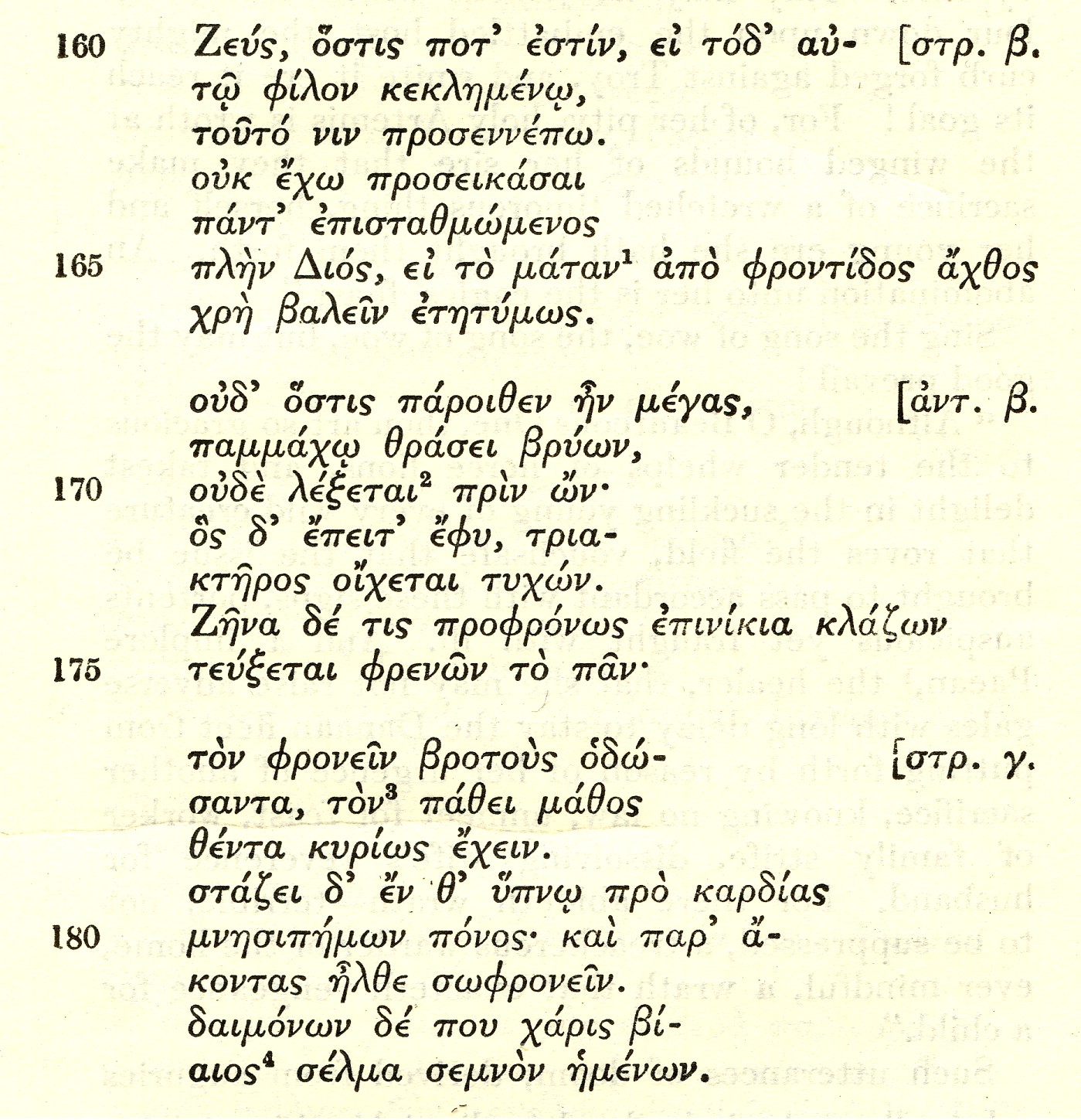

We are reminded of the fate of Cassandra, the Trojan princess and prophetess who could foresee the future, but was cursed with never having anyone believe her. A war captive brought back to Greece after the Trojan War, she and her story appear in Aeschylus' tragedy Agamemnon, the first play of the trilogy known as the Oresteia. That play contains the famous phrase pathei mathos "knowledge through (sad) experience," or, more colloquially, "learning the hard way" or "the school of hard knocks."

Aeschylus' Agamemnon: an accursed family

The Agamemnon tells of the homecoming of Agamemnon, king of the city of Mycenae and leader of the Greeks in the war against the city of Troy. The war, according to legend, was an act of revenge because the Trojan prince Paris had run off with Helen, wife of Menelaus, king of Sparta and brother of Agamemnon. (Helen was also the sister of Clytemnestra, Agamemnon's wife.) The play opens with the watchman watching for the signal flares relayed from Troy that will announce the defeat of Troy.

A chorus of elders, men who were too old to be sent to fight, enter and recapitulate the story of the Greek army's departure for Troy ten years ago. A failure of a favoring wind, which prevented the army from departing was attributed to a curse which could only be lifted if Agamamnon sacrificed his daughter Iphigeneia. Clytaemnestra has not forgiven her husband for the killing of their daughter. She has taken as her lover Aegisthus, son of Thyestes, brother of Agamamnon's father Atreus. Aegisthus has his own reasons for hating Agamamnon, as Agamamnon's father Atreus had murdered Thyestes' other children.

Pathei mathos in Agamemnon

The chorus sings "a song of anguish," extolling Zeus, king of the gods, while recapitulating Zeus' own accursed family, in which each generation, sons and grandsons, had conquered the previous generation of rulers. It is the law established by Zeus that "from experience comes knowledge" (pathei mathos v. 172), a phrase whose meaning has been debated by psychologists and theologists. A simple, literal meaning seems most appropriate: sometimes people learn only by having something horrible happen to them. The Chorus repeats the phrase again at v. 250 in slightly different form as "Justice (Dike) inclines her scales so that those who suffer learn (tois pathousin mathein)."

The Chorus does not yet know the full scale of the violence to come, but is fearful. By the end of the play, Agamemnon is murdered by Clytaemnestra. In the second play, The Libation Bearers, Agamemnon's son Orestes murders both Clytaemnestra and Aegisthus, and in the final play of the trilogy, "The Eumenides" ("The Kindly Goddesses," i.e. the Furies), Orestes is on trial in a court in Athens for the murder of his mother. He is acquitted, thanks to a vote by the goddess Athena, who claims, improbably, that the mother is not the true parent of a child, but merely a caretaker of the seed of the father, who is the true parent.

Cassandra's warnings to Agamemnon

Once again, we see warnings that were ignored. Agamemnon, on his return, brought with him as a captive (and concubine) the Trojan princess Cassandra (another reason for Clytaemnestra to hate him). Cassandra had been given the gift of prophecy by the god Apollo, but because she spurned him (the exact details differ in various accounts) he decreed that no one would ever believe her. Her warnings to the Trojans about their own impending doom at the hands of the Greeks had already been ignored. Cassandra foresees the disaster to come, and cries out hysterically. Her warnings are not believed, and she is killed along with Agamemnon.

Quotation of the Month, pathei mathosin Aeschylus' Agamemnon

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Greek and English, Aeschylus' Agamemnon verses 160-183, in which the Chorus of Elders ponders on the person of Zeus, and recounts the terrible history of the god, culminating in the famous words concerning the wisdom that comes from tragic experience.

Aeschylus' Agamemnon 160-183

|

Learning from tragic experienceZeus, whoever he is, if by this name |

The ruins of ancient Troy, with its many layers, in an illustration from Chrestos Tsountas and J. Irving Manatt, The Mycenaean Age,, 1897. The book was written not long after the pioneering excavations of both Mycenae and Troy by Heinrich Schliemann, and Schliemann's rediscovery of the actual location of ancient Troy, leading to the realization, now generally accepted, that the Trojan War was real.

Quotation for May, 2021

Dolphins' Friendship With Other Species: Homeric Hymn 7 to Dionysos |

Above: Boy playing the flute while riding on a dolphin, detail of red-figure stamnos, 360-340 B.C. from Etruria. Grupo de Alcesti, National Archaeological Museum, Madrid, Spain. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen, via Wikimedia.Top: Dolphins cavorting in the indoor pool and amphitheater at the Shedd Aquarium, Chicago. The Adler Planetarium and Lake Michigan are visible in the background. Photo by C.A. Sowa, Nov. 20, 2017.

A dolphin adopts a young whale

On May 17, 2021, scientists at the Far Out Ocean Research Collective in New Zealand reported seeing a female bottlenose dolphin caring for a pilot whale calf as if it were her own offspring. Earlier in the day, the dolphin was seen hanging out with a mixed group that included bottlenose dolphins, false killer whales, and pilot whales. It is not known what happened to the baby whale's own mother. This is not the first time that a bottlenose dolphin has adopted a calf of another marine mammal species. In another recent sighting, in November, 2020, a mother bottlenose dolphin was seen off the coast of Rangiroa Atoll in French Polynesia caring for a baby melon-headed whale as well as her own calf. There are many stories of dolphins developing a relationship with other sea creatures.

Do dolphins ever care for humans? There is evidence that dolphins' caring relationship with other species even extends to humans.

Dolphins' friendship with humans

Stories of dolphins rescuing people and their special relationship with humans are as old as antiquity, and some modern anecdotal evidence seems to point in this direction. There are several reports of swimmers menaced by sharks who found themselves surrounded by a pod of dolphins who drove off the sharks. Another pod of dolphins guided a rescue boat to the location of a group of scuba divers adrift at sea. Many disabled divers claim to have been transported to safety by dolphins, who acted protectively as they would with a helpless member of their own species. The reasons for this behavior are not well understood, but a number of these incidents are discussed on the web site Dolphins-World.

Dolphins in antiquity: Arion, Apollo, Dionysos, and Cretan bathrooms

Dolphins are everywhere in in Cretan and Greek art and in Greek poetry. Dolphins decorate the bathroom of the Palace of Knossos. Dolphins interact with gods and men in a variety of ways. In Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo, the god, having vanquished the she-dragon at Delphi, founds his temple on the slope of Mount Parnassus. Needing to staff his temple, he hijacks a Cretan ship by leaping on it in the form of a dolphin, forcing it to divert its course. He makes the sailors become his priests.

Herodotus, in Book I of his Histories, tells the story of Arion, lyric singer and poet bound for Corinth after winning a musical competition in Sicily, who was captured by pirates who wanted to steal his rich prize money. Given a choice of being killed or committing suicide by leaping into the sea, he requested permission to sing one last song. After doing so, he jumped overboard, where he was rescued by a dolphin, who carried him to land at Taenarum, at the far southern end of the Greek peninsula. He made his way to Corinth, where the pirates were going around claiming that he was still in Italy. A bronze figure of a man seated on a dolphin, now lost, was erected at a shrine in Taenarum.

Aelian (Claudius Aelianus, ca. 175-ca. 235 A.D.), a Roman teacher of rhetoric at the time of Septimius Severus, includes in his On the Nature of Animals (in Greek) a sadly sentimental tale of a dolphin who falls in love with a beautiful boy (Book 6.15). The two play together, and the dolphin lets the boy ride on his back. One day, exhausted after a vigorous day at the gymnasium, the boy flings himself on the dolphin's back, crashes into the sharp end of the animal's dorsal fin, and bleeds to death. The distraught dolphin carries the boy ashore and beaches itself, dying with his beloved. The two are buried in a common tomb, with a monument depicting a boy riding on a dolphin. In fact, dolphins (and whales) sometimes do die upon the beach, perhaps coming too close to shore and being stranded when the tide changes. Mass strandings occur, other dolphins perhaps trying to save an injured pack member, or simply following their leader. Could such occurrences have supplied the kernel of this sentimental story?

Oppian, a Greco-Roman poet writing in the 2nd century A.D., at the time of Marcus Aurelius, in his Halieutica ("On Fishing"), said that dolphins are beloved by Poseidon (Book 1.385) because they helped him find a wife, and in Book 5.415 he declared that "the hunting of Dolphins is immoral" and that "the gods abhor" the killing of dolphins "equally with human slaughter."

Sometimes men become dolphins. The pirates themselves become dolphins in the poem from which we take our Quotation of the Month, Homeric Hymn 7 to Dionysos.

The Homeric Hymn VII to Dionysos

In the Hymn to Dionysos, the god of wine and ecstasy appears as a handsome young man with wavy dark hair, wearing a purple robe, standing on a cliff overlooking the beach. Pirates seize him and drag him onto their ship, where they try to shackle him, hoping to steal not only his wealth but that of his obviously wealthy family. But the bonds fall from him, and he simply sits there smiling. Only the helmsman thinks this is a bad idea, and that the young man is probably some god, who should be released, lest he cause a storm and shipwreck. But the captain refuses, and gives the order to set up the mast and hoist the sail. At first the phenomena are benign. Wine flows across the deck, and vines bearing clusters of grapes grow up the mast and over the sail. Fruit-bearing vines and flowers cover the ship. At last the sailors request the helmsman put into port. But it is too late, and things get serious. A menacing bear and lion appear, and the lion attacks the captain. The sailors, in a state of shock, leap overboard, and are turned into dolphins. But Dionysos spares the prudent helmsman, and holds him back from jumping overboard. The Hymn ends with a common ending of a Homeric Hymn, a short invocation of the god (not included in the selection below).

Dionysos causes grape vines to grow on the ship's mast, and the pirates, who jumped overboard, are changed to dolphins. Cup by Exekias, ca. 540 B.C., Munich Staatlich Antikensammlung. Photo by R. Schoder, S.J., used in my Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns 1984, Chapter 9 "Epiphany of a God."

Quotation of the Month, from the Homeric Hymn to Dionysos

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Greek and English, the final revelation of Dionysos to the pirates, with its scary manifestations. The text is from the Oxford Classical Text of 1912, corrected edition 1961.

Homeric Hymn VII to Dionysos, vv. 32-57

|

A smiling Dionysos spooks the piratesSpeaking thus, [the captain] had the ship's mast and sail raised, |

Wooden panel representing a sea spirit cradling a dolphin in her arms, accompanied by two sister spirits while other dolphins cavort around. Wood carving by Christine Cooper Angier, my mother, 1930's.

Quotation for April, 2021

What is Infrastructure? Vitruvius De Architectura |

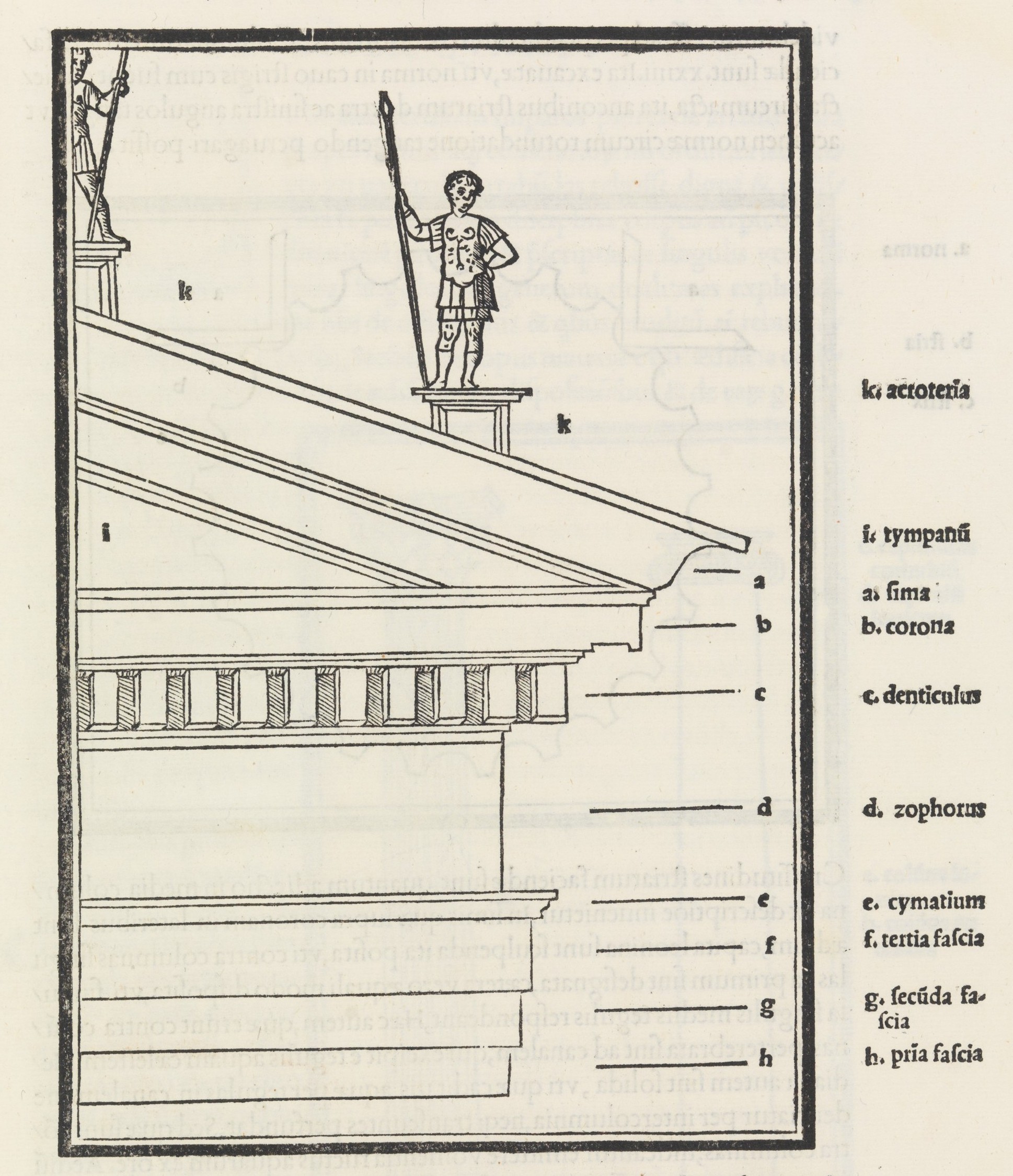

Above: The fourth century Cathedral of Fano, ancient Fanum Fortunae, perhaps incorporating parts of a basilica designed by Vitruvius. Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, photo by MarkusMark, August, 2009, via Wikimedia.Top: An illustration from the edition of Vitruvius de Architectura published in Venice in 1511 by Fra Giovanni Giocondo, Book 3 p. 31, detail. Metropolitan Museum.

A dispute over definitions: roads, bridges, and child care

The Democrats have introduced legislation to appropriate federal funds to improve infrastucture throughout the United States. It would fund what has traditionally been called "infrastructure," comprising roads, bridges, airports, railroads, and transit, including money for the Amtrak passenger rail system. It expands the definition for a modern age by including funds for Internet connections for underserved populations, especially in rural areas, much like the rural electrification program of an earlier era. But, defining "infrastructure" as the underlying framework that enables the smooth running of society, the proponents of the bill have included child care, elder care, free pre-kindergarten and community college education. These measures are wildly popular among people at large, but evoke howls of protest from Republican legislators. "That's not infrastructure!" they cry, ignoring the fact that state colleges, now grown into state universities, were founded in the nineteenth century to provide free higher education to the sons and daughters of working families.

The fight over whether to adopt a narrow or a wide definition of infrastructure is reminiscent of the "silo-ization" of much of our society, where we are not supposed to step out of our area of experience or expertise. Most recently we have seen this in resistance to encouraging police to step out of a semi-military role to render psychological or social services. In higher education, students are encouraged to specialize immediately, whether in business, art history, economics, or Classics, and after graduation, they are expected to "stay in their lane" and not comment on anything outside of their major. (Carrying this to a silly extreme, someone recently criticized President Biden's wife for daring to call herself "Dr." Jill Biden, when she is not a physician!)

The Greek philosophers as polymaths

It was not always thus. "Philosophy" today, for example, is considered an academic subject, with little connection to the workaday world. The word philosophia, however, means "love of wisdom," and the ancient philosophers were polymaths, occupied in all branches of knowledge. Aristotle was as much a scientist as a "philosopher" in our sense. The Stoics, whose name has unfortunately become a shorthand for people who endure pain and suffering without expression, believed that to accept the world as it is required them to understand that world. Posidonius, a Stoic philospher (ca. 135 B.C. - ca.51 B.C.) was a mathematician, musical theorist, astronomer, politician, and military tactician. He studied the effect of the moon on the tides and calculated the circumference of the Earth and the size and distance of the Moon.

"Epicurean" is another term that has also been distorted, to mean "overindulging" in a life of pleasure. But Epicurus himself (341-270 B.C.), while he believed in the value of happiness and tranqility (ataraxia, "freedom from being bothered"), was most famous for his improving on the theories of the earlier philospher Democritus (ca. 460-370 B.C.), who stated that all things are constructed of atoms. (His atomic theory is known to us from the Roman Lucretius' de Rerum Natura "On the Nature of Things.")

What is an architect? Vitruvius: Roman architect, engineer, inventor, city planner

The professions of architect and engineer have been similarly narrowed. Here again, the ancients would disagree, and a spectacular example is the Roman architect Vitruvius.

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (ca. 80-70 B.C.), is best known for his multivolume work De Architectura "On Architecture," but that title does not fully describe the scope of this undertaking. We know little of the life of Vitruvius, other than what he tells us himself in his book, but as far as we know, he served as a military engineer under Julius Caesar, specializing in the construction of siege engines. In later years the Emperor Augustus may have granted him a pension, and the De Architectura is dedicated to Augustus.

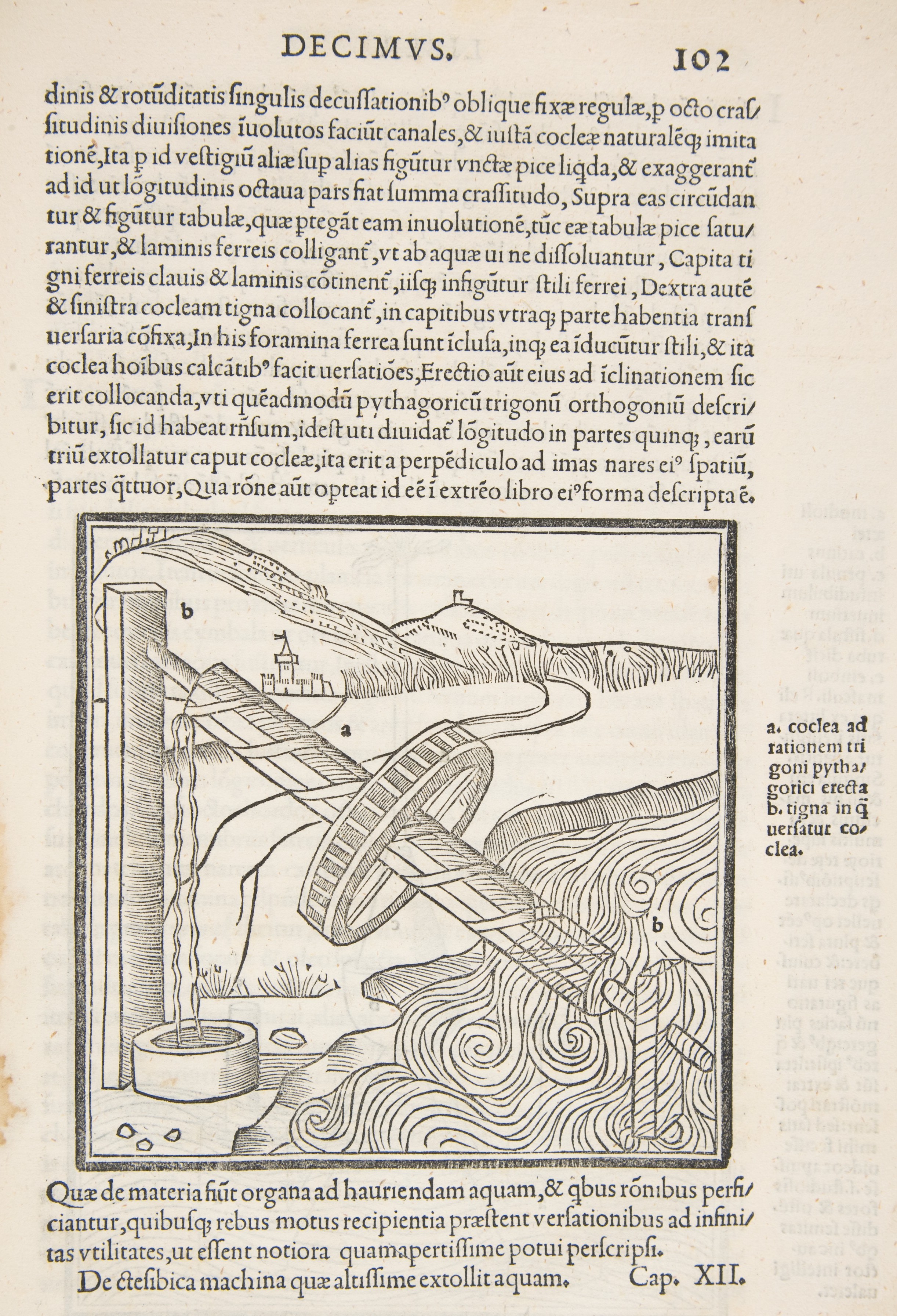

The word "architect" itself means "master builder," and the De Architectura is wide-ranging in the fields Vitruvius considered that the builder must be familiar with. He covers topics including mechanics, building materials, construction and contracting, town planning, music and acoustics (especially with regard to theater design). He discusses the effects of the winds blowing from different directions, the constellations and heavenly bodies (in the section on sundials and water clocks), and advises that the builder also be familiar with aspects of the law and medicine. He also describes the design of various machines, for war and for peaceful purposes, and he includes a design for a device for lifting water based on the Screw of Archimedes, which we discussed in the Quotation of the Month for March, 2021. It is Vitruvius who gives us the story of how Archimedes discovered the method of measuring the volume of an object by the displacement of water while getting into his bathtub (de Arch. 9.9-12).

Firmitas, utilitas, venustas

The most quoted words written by Vitruvius are his statement of the three most important qualities that a structure must have: firmitas, utilitas, venustas. Standing by themselves, they can be translated as "durability, usefulness, and beauty," but of course there is more to it than that, as Vitruvius goes on to tell us, briefly at first, then for the rest of the De Architectura. For firmitas he tells us, the foundations must go down to solid ground, and materials used should not be chosen simply for cheapness; for utilitas, the structure must fill its particular need, and be easy to get around in; for venustas, the structure should be pleasing and in good taste (elegans), and should be well-proportioned. Vitruvius was interested in ideal proportions, whether for a building or for the human body, and his measurements for the Vitruvian Man were the basis for the well-known drawing by Leonardo da Vinci.

Vitruvian Man, by Leonardo da Vinci, with notes from Vitruvius, ca. 1492. Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice. Image from Wikipedia, by Luc Viatour.

The Basilica at Fano

The only actual building that we know was designed by Vitruvius was the basilica built in 19 B.C. at Fanum Fortunae ("Temple of Fortune"), northeast of Rome, whose construction he describes in detail (De Arch. 5.1.6). Fanum Fortunae is today known as the Italian town of Fano. Vitruvius' building has long since disappeared, and even its exact location is unknown. Modern scholars have attempted to reconstruct what it looked like from Vitruvius' description. Since it was common to reuse pieces of ancient buildings in newer construction, it has been conjectured that parts of Vitruvius' shrine may have become part of the twelfth-century Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta in Fano, which itself was built over an older cathedral destroyed by fire in 1111. The cathedral façade, pictured at the top of this article, was restored in the 1920's.

Manuscripts of the De Architectura were widely circulated in succeeding centuries, and were admired and followed by generations of architects, but Vitruvius' original drawings were lost. The first printed edition, with woodcuts based on Vitruvius' descriptions, was published in Venice in 1511 by Fra Giovanni Giocondo. Selections of these illustrations appear at the top and below.

Quotation of the Month, from Vitruvius, de Architectura

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Latin and English, Vitruvius' famous definition of architecture in Book I of De Architectura. The text is from the Teubner edition of 1912, which can be found on the Perseus website.

Vitruvius Book I Chapter 3.1-2

|

Vitruvius on the definition of architectureArchitecture has three divisions: building, the making of timepieces, and mechanical construction. Building is divided into two parts, of which one is the erection of walls and works of general use in public places, and the second is the putting up of private structures. Of public works there is a tripartite distribution: the first area is defense, the second religion, the third common convenience. Under defense there is the planning of towers and gates designed to permanently repel enemy attacks; under religion there is the erection of shrines and sacred temples to the immortal gods; under common convenience there is the disposition of places for public use, such as ports, markets, colonnades, baths, theaters, promenades, and other similar facilities that are decided upon for public locations. All of these must be made so that there is a calculation of

durability, usefulness, and beauty. Durability will be achieved

when foundations are carried down to solid ground, and a choice

of materials is made without cost-shaving;

utility, on the other hand, requires that the arrangement of

the place is faultless and offers no impediment to use, and that

the exposure of each class of building is suitable and

appropriate: beauty indeed, will be achieved when the

appearance of the work is pleasing and elegant and the

proportions of the parts have the correctly reasoned

measurements of symmetry.

|

A machine for raising water, based on the Screw of Archimedes. An illustration from the edition of Vitruvius de Architectura published in Venice in 1511 by Fra Giovanni Giocondo, Book 10 p. 102.

Quotation for March, 2021

For Pi Day, Archimedes of Syracuse: Plutarch, Life of Marcellus |

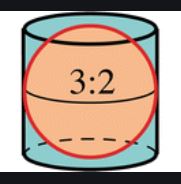

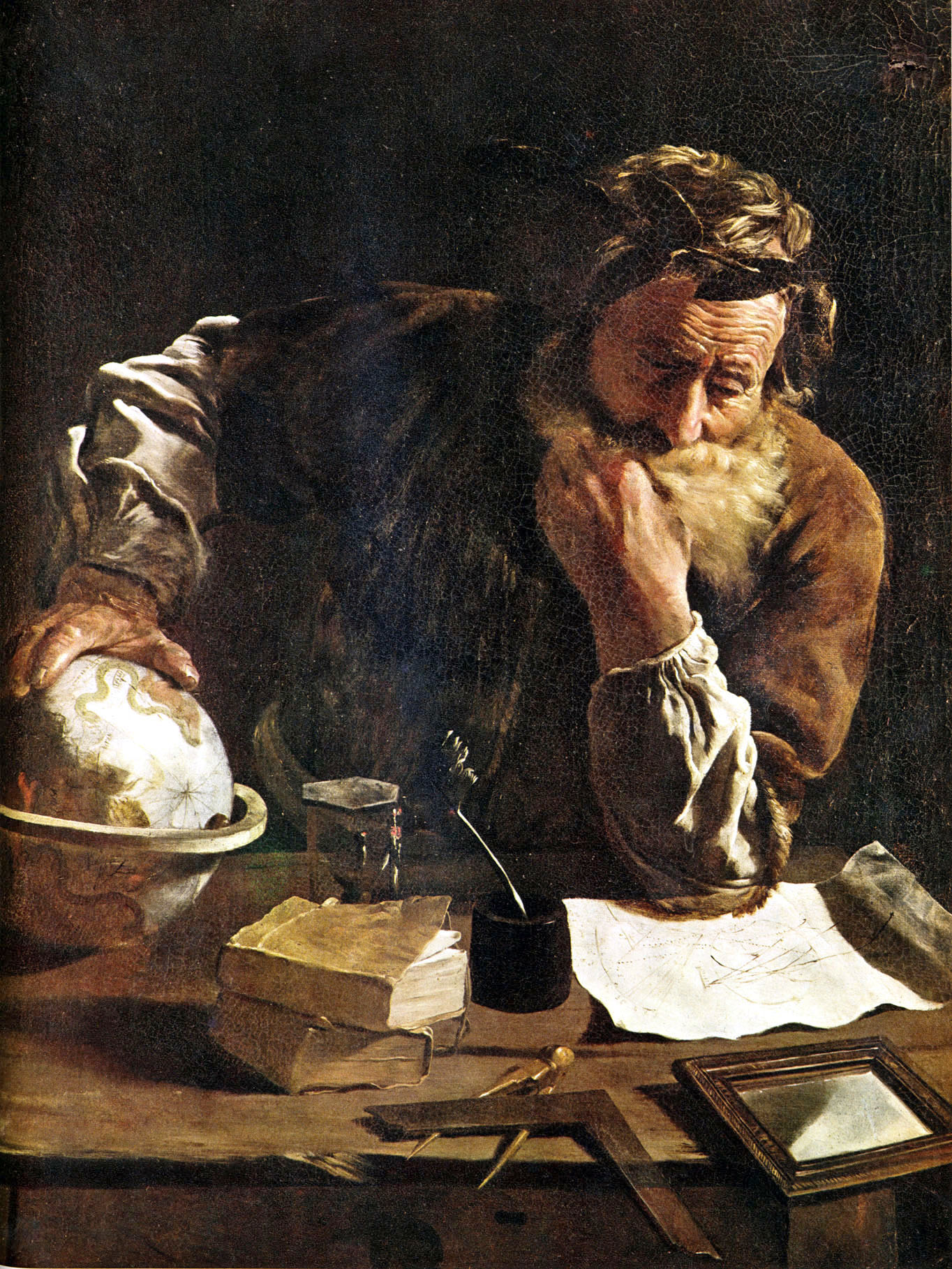

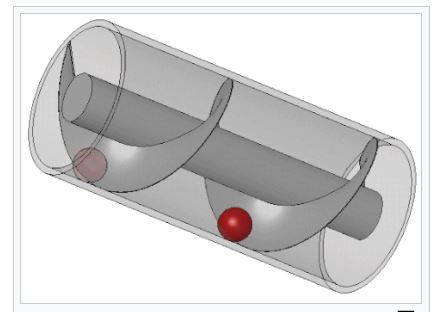

Above: Archimedes, as painted by Domenico Fetti, ca. 1620. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden.Top: Diagram showing that the ratio between the volume and surface areas of a cylinder and a sphere contained within it are exactly 3:2. Archimedes desired that this diagram be inscribed on his tombstone.

Celebrating Pi Day

On March 14, fans of mathematics celebrated Pi Day. The numeric equivalent of the date is 3.14, representing the mathematical constant pi, usually written with the Greek letter

It is the closest approximation of the ratio between the circumference of a circle and its diameter. The value of pi is often given as 3.14159, but even this is an approximation, as the true value has never been ascertained, although many ingenious mathematical methods have been tried. In 2020 there was a claim that the value had been computed to 50 trillion digits. The use of the letter pi comes from its being the first letter of the Greek periphereia, the circumference of a circle — the Latin circumferentia being an exact translation of the Greek, "a carrying around."

To commemmorate Pi Day, some restaurants offer free or discounted helpings of pie!

For our Quotation of the Month, we celebrate the life of one of the ancient scientists who developed an ingenious method of approximating the value of pi, Archimedes of Syrcuse.

Archimedes of Syracuse, scientist and inventor

The Greek Archimedes (ca. 287 B.C. - 212 B.C.), famous for his inventions, developed a method of approximating pi by computing the dimensions of a series of polygons inside and outside the figure until he approached the desired value. His computations were achieved without the aid of modern calculus. Archimedes was not the first to compute a value for pi. The Chinese, Babylonians, and Egyptians also developed methods for approximating its value. But this was only one of many mathematical calculations made by Archimedes.

Archimedes, born in Syracuse on the island of Sicily, is most famous for his practical inventions, especially the Archimedes Screw, used even today for lifting water as well as other materials. A corkscrew-shaped blade inside of a cylinder is made to revolve by turning a crank by hand or machine, so that as it turns, anything placed or scooped onto it is lifted. (See the diagram at the bottom of this item.) He also invented innovative types of pulleys and defined the principle of the lever, of which he is supposed to have said "Give me a place to stand, and I can move the world." He also designed war engines with which the army of Syracuse was able to fend off the invading Romans for two years.

Archimedes the mathematician

Less well known in popular lore is his work in pure mathematics, which he considered his most important work. This included his aforementioned computation of pi. He also made other geometrical computations, including the volumes and areas of various geometrical figures. In a famous anecdote told by Vitruvius, he discovered that the volume of an object could be determined by seeing how much water it displaced. He made this discovery while taking a bath, seeing how the water level rose as he got in, uttering the famous phrase "Eureka!" (heureka!) "I have found it!" In one of his favorite discoveries, he computed the ratio of the surface area and volume of a sphere to a cylinder of equal height and radius, which he determined to be 2:3. He considered this latter discovery to be of such importance that he requested that a representation of it be inscribed on his tombstone. This was done, and the tombstone was seen and described by Cicero in 75 B.C. when Cicero was serving as quaestor in Sicily. Cicero found the tomb in neglected condition, and had it cleaned up. (See the figure above.)

Archimedes left several treatises on his mathematical work, but none on his practical inventions, considering them to be, by comparison, "ignoble and vulgar" (agennê kai banauson), according to Plutarch (Life of Marcellus 17.4).

The Siege of Syracuse by the Romans under Marcellus

During the Second Punic War, fought by Rome against the Carthaginians under Hannibal, Sicily, including the city of Syracuse, had defected to the Carthaginian side. Syracuse proved to be particularly difficult to crack, thanks in large part, to the inventions of Archimedes. In 214 B.C., the Romans, under the proconsul Marcus Claudius Marcellus laid siege to Syracuse. He brought the full might of the Roman navy against the city's defenses. Archimedes, however, designed engines that could lob huge stones and other weights down upon the ships, as well as other machines. Perhaps his most amazing device was an enormous crane or claw that could seize a ship and dash it against the cliffs beneath the city walls or lift it up and shake it about until all the crew fell out.

Marcellus was finally able to take the city by entering it by an unguarded tower while the inhabitants were celebrating a festival of Artemis. When Marcellus looked down upon the beautiful and prosperous city, he is said by Plutarch to have wept to think that it would soon be plundered and destroyed, for there were many who wanted it burned to the ground. This he would not permit, although he was unable to stop his men from plundering it.

Marcellus mourns the death of Archimedes

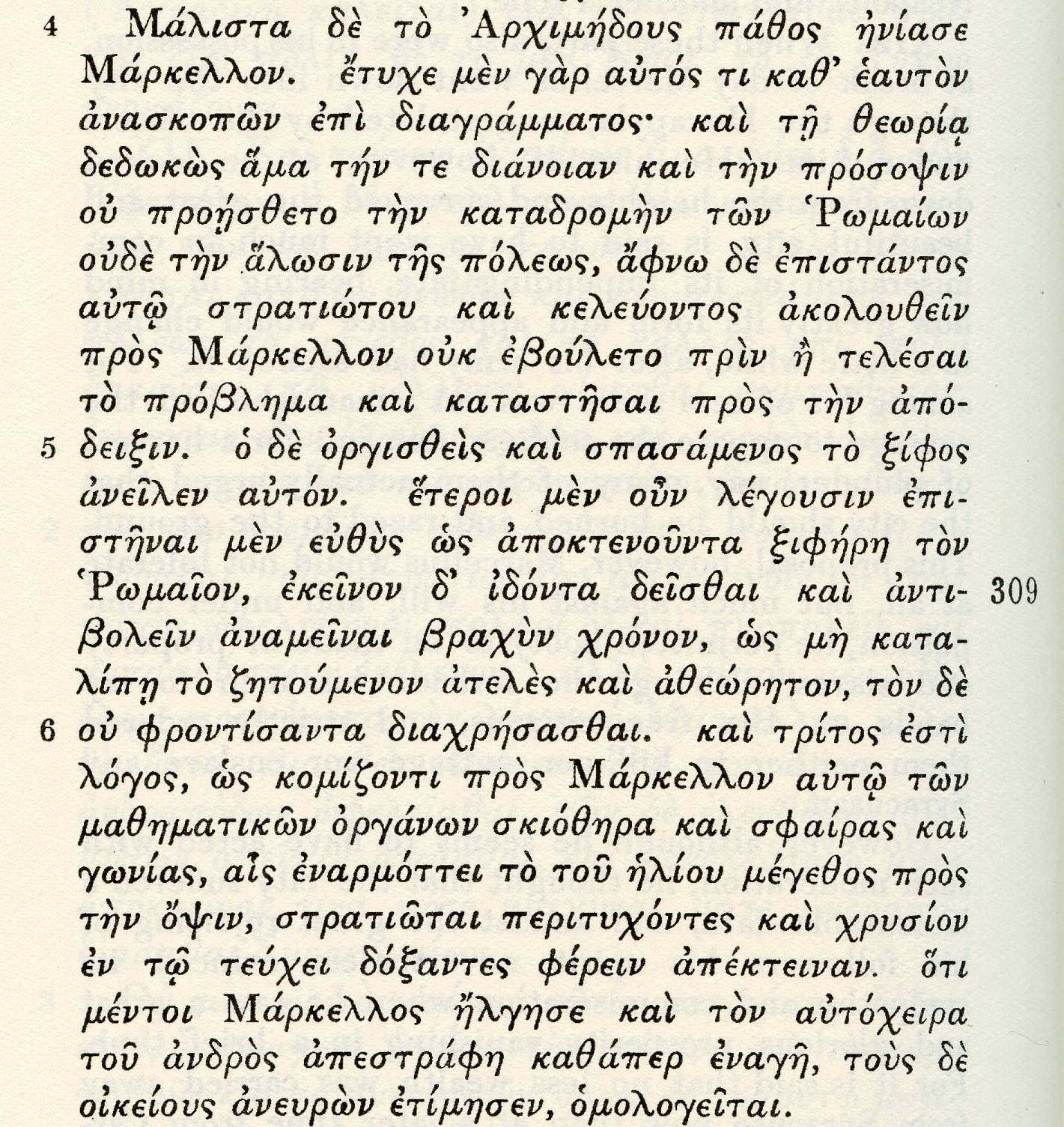

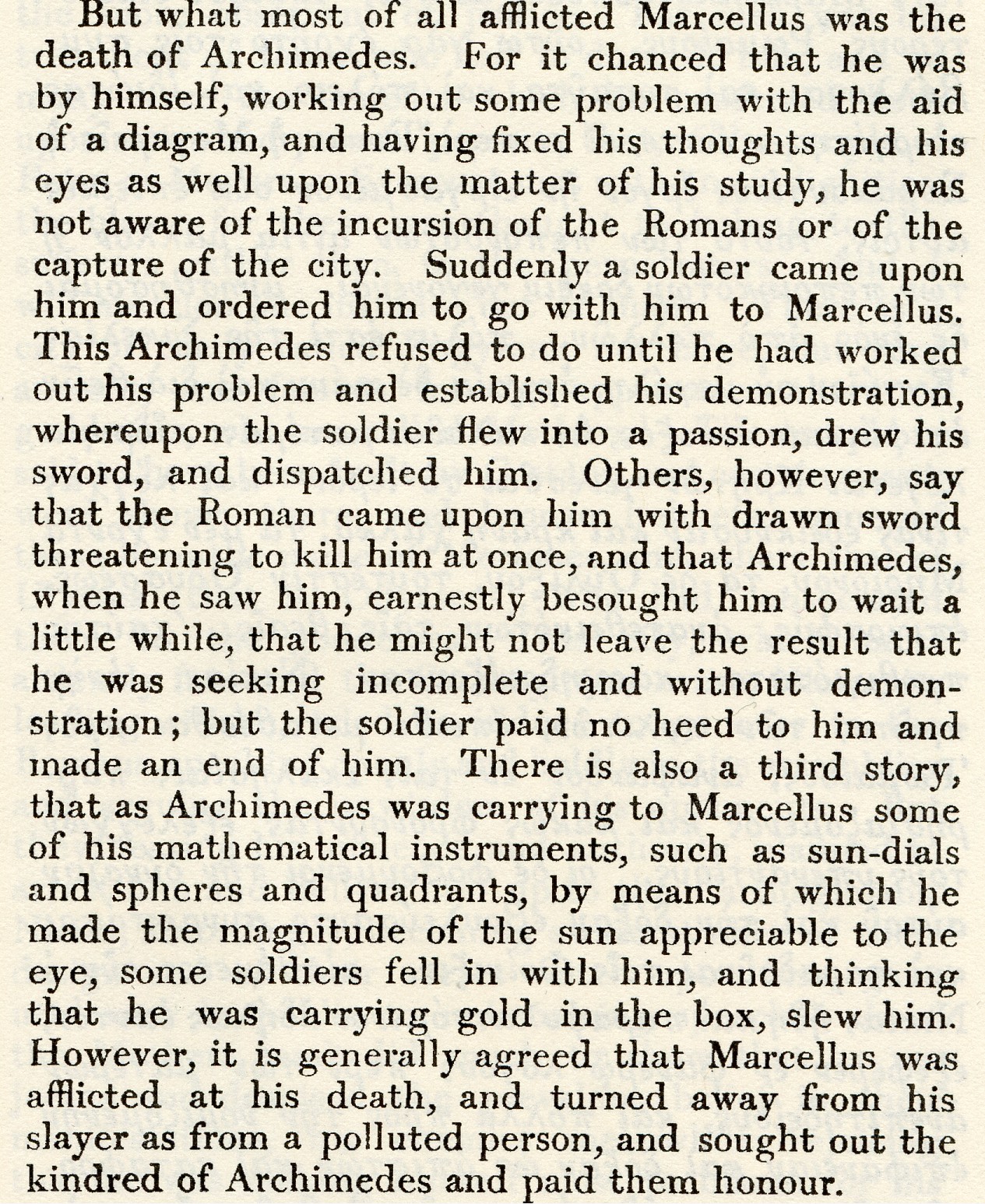

Archimedes is said to have died at the hands of a Roman soldier while he was intent on solving a mathematical problem. According to Plutarch, a soldier summoned Archimedes to go with him to Marcellus, but he refused to leave until he had solved the problem and completed its demonstration. The soldier, angered, drew his sword and killed him. Plutarch also offers two other versions, one in which the soldier threatened him as soon as he came in, and another in which Archimedes was carrying some astronomical instruments to Marcellus, and some soldiers thought he was carrying gold, for which they killed him. Marcellus, in obvious admiration for the genius of Archimedes, was outraged, and shunned the killer as a polluted person, going to the relatives of Archimedes and paying them honor.

Marcellus took as his only loot from the city two of Archimedes' devices, which showed the motions of the Sun, Moon, and planets. According to the narrative told by Cicero in his dialogue de Re Publica, Marcellus kept one for himself and donated the other to the Temple of Virtue in Rome.

The world's first oceangoing steamship using a screw propeller was the British ship SS Archimedes, launched in 1839.

Quotation of the Month, from Plutarch's Life of Marcellus

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Latin and English, part of Plutarch's Life of Marcellus that describes the death of Archimedes. Both the text and the translation are from the Loeb edition of 1917.

Plutarch Marcellus 19.4-6

|

Marcellus mourns the death of Archimedes

|

Diagram of Archimedes' screw. By turning the device, an object can be lifted, or a ship propelled.

Quotation for February, 2021

For Valentine's Day, a Soldier's Wife Writes to Him: Propertius Elegies 4.3 |

Above: Roman soldiers (infantry and cavalry). Illustration from Caesar's Commentaries, ed. Francis W. Kelsey, 1918.

Valentine's Day in a time of isolation

In February we celebrated Valentine's Day, but because of the quarantine imposed during the pandemic, many of us were unable to be with loved ones on special occasions. We were unable to visit family and friends, either because they were in the hospital with limited or no visiting privileges, or because they live perhaps hundreds or thousands of miles away from us. And of course military families are regularly separated, often for long periods of time.

For this month's Quotation of the Month, we bring you a fictionalized letter from an ancient Roman wife to her soldier husband, serving in one of the Emperor Augustus' many foreign campaigns, written by the Roman poet Propertius.

Augustus' foreign conquests

Under the rule of the Emperor Augustus, which extended from 30 B.C. (when Antony and Cleopatra were defeated at the Battle of Actium) until his death in 14 A.D., Rome, while peaceful at home, was engaged in almost constant foreign warfare. Augustus extended Roman power by consolidating conquests in Gaul, Spain, Egypt, the Lower Danube, and the Middle East. The land of Germany, however, eluded him.

In 26 B.C. Augustus ordered the prefect of Egypt, Aelius Gallus, to invade the Sabaeans of the lower Arabian peninsula. Rome already controlled the upper part of the peninsula, ruled by the Nabataeans. The Nabataean capital was the fantastic rock-carved city of Petra, in present day Jordan. The lower part of the peninsula, known as Arabia felix ("Fortunate (or Fertile) Arabia") in present day Yemen, was a source of the sought-after spices of myrrh and frankincense. Conquest of Arabia would also give the Romans control of both sides of the entrance to the Red Sea and hence access to trade with India and the Horn of Africa. The campaign went badly, and the Roman troops suffered heavy losses, although the Sabaeans eventually entered into an uneasy relationship with the Roman Empire. It is thought that Propertius' letter to a soldier from his wife may date from this campaign.

Propertius' Elegies

The Roman poet Sextus Propertius (ca. 50-45 B.C. - ca. 15 B.C.) was a member of the circle of poets around Augustus and his principal advisor, the wealthy Maecenas, which also included Horace, Vergil, and Gallus. Propertius is known to us from four books in the elegiac meter, with alternating long and short lines. (Some scholars have rearranged the poems of the four-book manuscript tradition into five books, which can make the numbering hard to follow.) His most memorable poems are those addressed to a woman he calls "Cynthia." He often refers to her as a docta puella, or "learned girl," and she herself is described as writing poetry. The relationship did not go smoothly, and eventually they broke up. In his last and most poignant "Cynthia" poem (IV.7), Cynthia has died, and appears to him as a ghost, sad and disappointed, complaining that when she expired, alone and forgotten, he did not even come to her funeral. She requests a short epitaph on her tomb, easily read by the traveller, "as he runs by." Promising (or threatening?) to see the poet in the next world, she departs, "slipping from his embrace."

In his later poems, Propertius branched out more, increasingly presenting characters other than himself. In Elegy IV.11, another shade, that of Cornelia, a relative of Augustus, addresses her widowed husband, Aemilius Paullus. She encourages him to move on, and even, if he wishes, to remarry.

Propertius's poetry is marked by a sometimes complicated use of language, and by allusions to obscure Greek and Roman mythology. This is true of the poem that is our Quotation of the Month (IV.4), in which he speaks in the voice of another woman, the lonely wife of a Roman soldier, away fighting in one of Augustus' endless wars.

A lonely wife writes to her soldier husband

In Elegy IV.3 (or V.3 in editions of five books) a woman named "Arethusa" writes to her husband "Lycotas" in the army. These are obviously pseudonyms (Arethusa was the name of a famous nymph), but we do not know who they represent; they may be fictional characters. Lycotas has been away for years, but she faithfully weaves clothing to send to his camp and is worried about his health. She remembers all the things that went wrong at their wedding, a bad omen for their marriage. She curses the man who invented war, and compares him to the accursed mythological character Ocnus, condemned forever to weave a rope which a hungry ass keeps eating (a painting of Ocnus is described in Pausanias Book X.29.1).

Arethusa is alone in bed, comforted by her sister and a nurse, who tells her optimistic lies that it is only the weather that delays him. She kisses his weapons that he has left at home. She is also comforted by her pet puppy, Craugis, who alone shares her bed (the name is from the Greek kraugê, the "baying" of a dog; perhaps we should call her "Woofie"!).

Arethusa envies the Amazon queen Hippolyte, who fought like a man, and wishes she could join Lycotas in the army. Interestingly, she consults a map to see all the places he has been, and to learn about them. She seems to be a docta puella, an educated girl like Cynthia. She makes offerings at all the altars, and pays attention to omens — a hooting owl, a sputtering candle (a good omen) which must be acknowledged by a sprinkling of wine. She is worried that he may be having affairs, and says that she only wants him back if he is faithful. But she assumes that he will be awarded the pura hasta, the ceremonial spear that was a badge of honor for those who had distinguished themselves in war.

Quotation of the Month

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Latin and English, Propertius' Third Elegy from Book IV, taken from the Loeb edition of 1916.

Propertius, Elegies Book 4, No. 3

|