These are quotations for the year 2019. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2019, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2019 |

Below are quotations for the year 2019. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2019

Click on a link to read each quotation

2019

- December, 2019: For the Season of Gift Giving: Catullus' Friend Calvus Gives Him a Joke Present (Catullus No. 14).

- November, 2019: Fires Consume the Earth as Phaethon Falls: Ovid Metamorphoses Book II.

- October, 2019: For Halloween, Roman Lares and Lemures as Spirits of the Dead.

- September, 2019: To Celebrate the Sesquicentennial of the Periodic Table, Empedocles on the Four Elements.

- August, 2019: For Women's Equality Day: The Poetess Corinna tells of the Marriages of the Daughters of Asopus.

- July, 2019: For the Anniversary of the Moon Landing: Anaxagoras Determines the Moon's True Nature and is Parodied by Aristophanes.

- June, 2019: Trade With China — The Ancient Silk Road, as Known to the Greeks and Romans: Vergil's Georgic II vv.109-139.

- May, 2019: For Spring Showers and Flowers: The Roman Festival of the Floralia, Complete With Weird Behavior, As Described by Juvenal's Satire No. 6.

- April, 2019: For Easter, Passover, Earth Day and Arbor Day, an Invocation to Diana by Catullus.

- March, 2019: Arcturus and migratory birds herald the coming of spring (Hesiod, Works and Days 564-570.

- February, 2019: A Supermoon for the Snow Moon of February: Homeric Hymn XXXII to Selene.

- January, 2019: Extreme Weather and Climate Change Deniers: Rejection of Science, Ancient and Modern (Lucretius De Rerum Natura Book I).

Quotation for December, 2019

For the Season of Gift Giving: Catullus' Friend Calvus Gives Him a Joke Present |

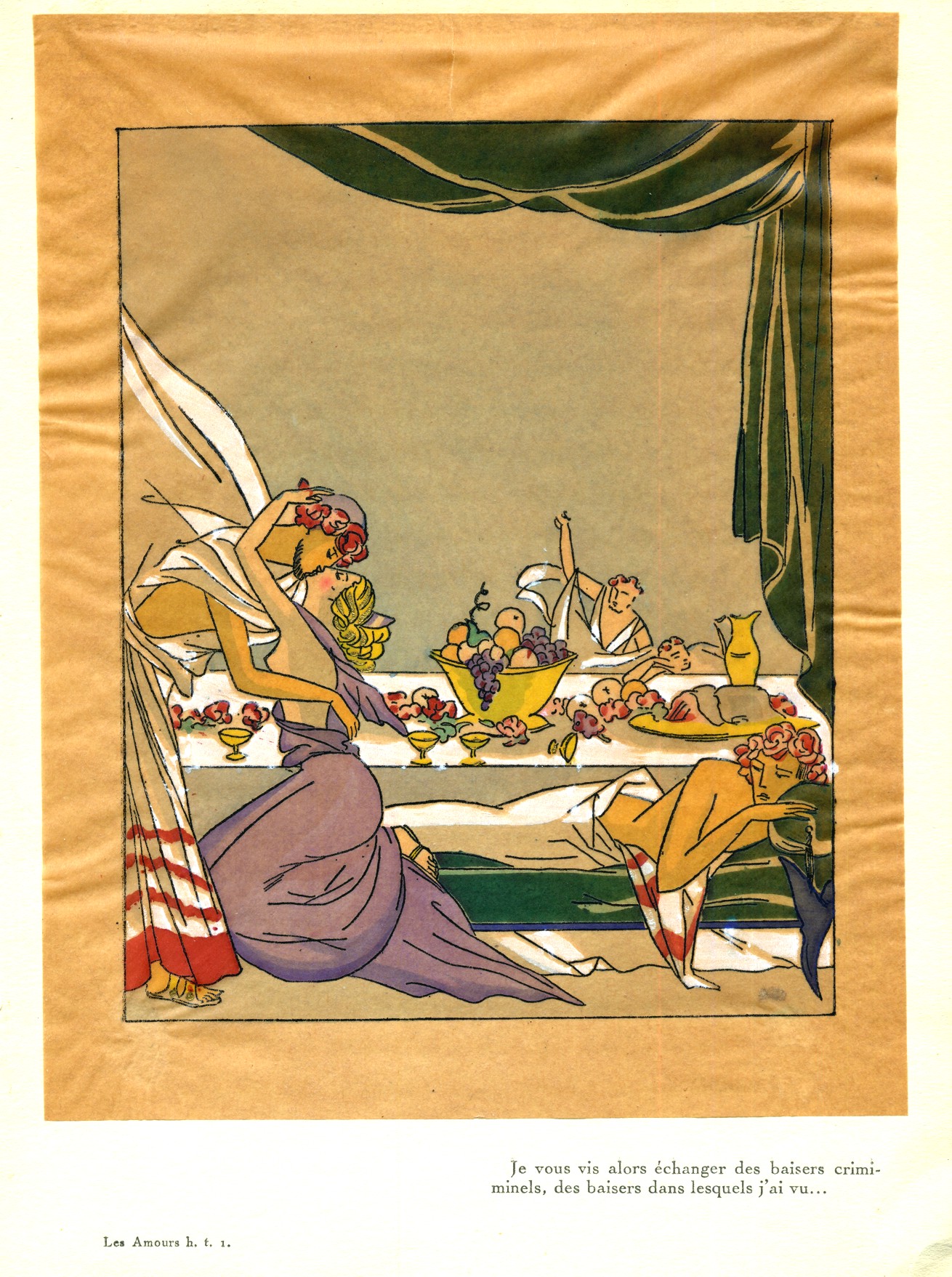

Above: A romantic conception of a Roman Banquet, after a painting by Albert Baur (1835-1906). Title: "Triclinium." Source: Illustrierter Katalog der III. Internationalen Kunstausstellung (Münchener Jubiläumsausstellung) im Königl. Glaspalaste zu München, München 1888, via Wikimedia. Banqueting and partying were important aspects of the winter festivals of Saturnalia and the month-long Brumalia that led up to the Saturnalia.

A season of winter holidays

Now is the time of winter holidays, all crowded around the Winter Solstice, when, in the Northern Hemisphere, the days that have been getting shorter and shorter and more and more gloomy, start to get longer. The Sun seems to halt in the sky, thinking better of its decision to shorten the day (the word solstitium literally means "sun standing (still)" from sol + sisto). Although the snowiest months are still to come in January and February, there is a sense of optimism, reflected in the holidays of the season: Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, New Year's, and celebrations of the Solstice itself. In agricultural communities, seeds that were sown in the fall are tucked up safely beneath the ground and are ready to germinate and sprout in the spring.

The Brumalia and the Saturnalia

In ancient Rome, the premier winter festival was the Saturnalia. It was celebrated in honor of the god Saturn. An ancient agricultural god, Saturn was said to have presided over a Golden Age of plenty and peace. Saturn later became identified with the Greek Kronos, and was known as the father of Jupiter, king of the gods, along with Neptune, Pluto, Juno, Ceres and Vesta. The Saturnalia was celebrated on December 17 of the Julian calendar, but was extended eventually to last for several days. The Saturnalia was marked by banquets and other celebrations, and was the occasion of gift-giving, often of joke gifts. Society was turned upside down, with masters and slaves exchanging places.

Leading up to Saturnalia before the main festival was the month-long celebration of the Brumalia, or Winter Festival. Bruma was a word meaning the Winter Solstice, or winter itself, being another form of the word brevissima, or "shortest (day)." The Brumalia was also celebrated by nights of feasting, merriment, and celebration. Farmers would sacrifice pigs to Saturn and Ceres. Vine-growers sacrificed goats in honor of Bacchus, god of the grape vine.

As a joke, Catullus' friend Calvus gives him a book of bad poems

As a gift for Saturnalia, probably in 56 B.C., the poet Catullus received a joke gift from his friend Calvus, a fellow poet and lawyer. Expecting a copy of Calvus' latest poems, Catullus was horrified to find a scroll containing a selection of the WORST poems imaginable! The "gift" arrived the day before the Saturnalia, ruining the day for Catullus, who vows that the next day he will go to the booksellers and find an equally execrable selection of awful poetry to send to his friend. The story is told in Catullus Poem Number 14.

Below, in Latin and English, is Catullus Number 14. Catullus speaks of hating Calvus "with the hatred of a Vatinius," referring to Calvus' famous speech of accusation against the corrupt politician Vatinius. Catullus suspects that the collection of bad poems was given to Calvus as payment by a client named Sulla, a teacher of grammar (not to be confused with the famous Roman general Lucius Cornelius Sulla). Catullus banishes the whole collection of bad poets (by throwing them in the trash basket?), telling them to "go back whence you brought your unhappy feet," with a pun on "footsteps" and the metrical "feet" of poetic composition.

Catullus 14Ni te plus oculis meis amarem,iucundissime Calve, munere isto odissem te odio Vatiniano: nam quid feci ego quidve sum locutus, cur me tot male perderes poetis? Isti di mala multa dent clienti, qui tantum tibi misit impiorum. Quod si, ut suspicor, hoc novum ac repertum munus dat tibi Sulla litterator, non est mi male, sed bene ac beate, quod non dispereunt tui labores. Di magni, horribilem et sacrum libellum! Quem tu scilicet ad tuum Catullum misti, continuo ut die periret, Saturnalibus, optimo dierum! Non non hoc tibi, false, sic abibit. Nam si luxerit ad librariorum curram scrinia, Caesios, Aquinos, Suffenum, omnia colligam venena. Ac te his suppliciis remunerabor. Vos hinc interea valete abite illuc, unde malum pedem attulistis, saecli incommoda, pessimi poetae. |

A book of terrible poems (ugh!)If I did not love you more than my own eyes,delightful Calvus, I would hate you for this gift with the hatred of Vatinius. For what have I done or what have I said that you would destroy me wrongly with so many poets? May the gods give many evils to that client of yours, who sent you such an ungodly bunch. But if, as I suspect, Sulla the grammarian gives you this newly discovered gift, it is not bad for me, but well and blessed, because your works do not disappear. Great gods! Horrible and accursed little book! Which you evidently sent to your Catullus so that he might perish the next day, on the Saturnalia, the best of days! No, no, false one, it will not end this way for you. For as soon as it becomes light I shall run to the book-boxes of the scribes, and I will collect the Caesius-es, Aquinus-es, Suffenus, all the poisons and I shall repay you with these punishments. But you, farewell and go from here to there, whence you have brought your unhappy feet, an inconvenience to our age, you worst of poets. |

A Bacchanalian procession. From a red-figured vase painting, lithograph ca. 1840, in the collection of C.A. Sowa. At the Brumalia vine-growers would sacrifice goats to Bacchus.

Quotation for November, 2019

Fires Consume the Earth as Phaethon Falls: Ovid Metamorphoses Book II |

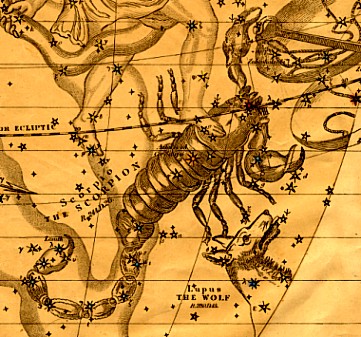

Above: Scorpio constellation. Terrified of the venomous Scorpion, Phaethon lets go of the reins of the chariot of the Sun. (Image: detail from Burritt's Geography of the Heavens, 1856. Note Libra, the scales, to the right of Scorpio, a "new" constellation formerly considered part of the creature's claws.)Top: Helios' horses. Detail of sculpture shown at the bottom of this essay.

Wildfires rage across the earth

Wildfires are consuming forests and towns in both the north and south hemishperes. In California, several enormous fires have raged in Riverside, Los Angeles, and Santa Barbara Counties in the south, and in several counties in northern California, where the entire town of Paradise in Butte County was destroyed. In Australia, fires have destroyed koala habitat, and have killed many of these already endangered animals.

In a number of cases, these fires have been caused by human ignorance and carelessness. Some have been started by downed power lines, or lines that have been badly maintained. One was started by a fire in a trash truck that caught fire, another by a controlled burn that got out of hand. Some of the destruction was caused simply by people building houses next to or even in dense forests without making them fireproof. Global warming doubtless plays a part, increasing the frequency and duration of droughts and deadly storms.

The myth of Phaethon

The role of human carelessness and hubris in the origins of an earth-consuming conflagration has its analog in an ancient story, the myth of Phaethon, who drove the chariot of his father, the Sun, while ignorant of how to control it, thereby setting the world on fire.

The name Phaethon is Greek, and means "The Shining One." Euripides wrote a play about him, which now exists only in fragments. Plato used the story in his Timaeus. The fullest account of Phaethon's wild ride appears, however, in the Metamorphoses of the Roman poet Ovid. As usual, that poet imagines poignant details, both physical and emotional, of all the characters, and makes the story come alive in all its mad manifestations.

Ovid's story of Phaethon's wild ride

In Ovid's telling, Phaethon is being taunted by his friend Epaphus, who says that Phaethon is not telling the truth when he says that Phoebus, the Sun, is his father (Metamorphoses I.750-754. Epaphus is the son of Io, who had earlier been turned into a cow, but that is another story, told both by Ovid in Metamorphoses Book I and by Aeschylus in Prometheus Bound).

Phaethon goes to his mother Clymene for confirmation of his parentage, and she advises him to visit Phoebus in his gleaming palace where the Sun rises in the East, which he does in Metamorphoses Book II. Phaethon visits his father's palace and is dazzled by its radiance. His father, embracing him, confirms his lineage, and to prove it, promises his son anything he wants. Big mistake. Phaethon asks to drive his father's chariot and horses for one day. His father instantly regrets his promise, and tries to dissuade his son. Unable to do so, he warns him of the dangers of the trip, the steepness of both ascent and descent, and the danger of going either too high or too low. Interestingly, he gets one piece of science right, when he has the world revolving in a direction counter to the track of the Sun, creating a force similar to a headwind.

Phaethon starts off, but immediately realizes that he is in over his head. The horses recognize the unfamiliar charioteer, who is of lighter weight than they are accustomed to and causes the chariot to be out of balance. Phaethon does not know how to control them, and realizes that he does not even know their names (The names of the horses, for the record, are stated in vv. 153-154; they were named Pyrois, Eous, Aethon, and Phlegon — "Fire," "Dawn," "Blaze," and "Flame.") Phaethon drives too high, and finds himself among the monsters of the constellations. He is completely freaked out at the Scorpion, whose body, poisonous sting, and claws occupy the space of two constellations. This, by the way, is true. It was only in Roman times that the "claws" were deprived of their front stars, which became a separate sign that we know as Libra, the Scales. Vergil alludes to this division in the Prolog to his Georgics, where he flatters the Emperor Augustus by suggesting that he will become a constellation, and that the Scorpion will draw in his claws to make room for him (Georgic I.34-35).

Setting the world on fire

Utterly terrified, Phaethon drops the reins, and the horses, feeling the reins lying loose on their backs, go totally out of control, going every which way, now climbing high, now plunging to earth, where the Moon is surprised to see her brother's chariot below hers. The entire world becomes ablaze, with entire cities on fire. Rivers dry up, and the sea level sinks, causing new islands to form. (Here, of course, Ovid's science is wrong, as global warming is causing the sea level to rise, as the glaciers melt!) Neptune hides his face, unable to endure the heat, and the Ethiopians, their overheated blood rising to the surface, acquire their dark complexion.

Finally Earth, distressed and suffering, intervenes, asking Jupiter to take action. The King of the Gods, having no clouds or rain to send because of the heat, strikes Phaethon with a thunderbolt, hurling him from the chariot, which is wrecked. The horses break free, and presumably find their way back to the barn.

The Sun, grieving for his son, hides (causing a solar eclipse). Phaethon's sisters, unable to bear their grief, grow foliage and bark, slowly turning into trees. Their tears become amber, which will be worn as jewelry by (ta-da!) the brides of Rome. Phaethon's friend and kinsman Cycnus becomes a swan.

Below, in Latin and English, is a portion of Ovid's story, where Phaethon loses control of the horses and the earth begins to catch fire.

Ovid Metamorphoses II.195-234Est locus, in geminos ubi bracchia concavat arcusscorpius et cauda flexisque utrimque lacertis porrigit in spatium signorum membra duorum. Hunc puer ut nigri madidum sudore veneni vulnera curvata minitantem cuspide vidit, mentis inops gelida formidine lora remisit. Quae postquam summum tetigere iacentia tergum, exspatiantur equi, nulloque inhibente per auras ignotae regionis eunt, quaque impetus egit, hac sine lege ruunt altoque sub aethere fixis incursant stellis rapiuntque per avia currum. Et modo summa petunt, modo per declive viasque praecipites spatio terrae propiore feruntur. Inferiusque suis fraternos currere Luna admiratur equos, ambustaque nubila fumant; corripitur flammis ut quaeque altissima, tellus fissaque agit rimas et sucis aret ademptis. Pabula canescunt, cum frondibus uritur arbor, materiamque suo praebet seges arida damno. Parva queror: magnae pereunt cum moenibus urbes, cumque suis totas populis incendia gentes in cinerem vertunt. Silvae cum montibus ardent, ardet Athos Taurusque Cilix et Tmolus et Oete et tum sicca, prius creberrima fontibus, Ide, virgineusque Helicon et nondum Oeagrius Haemus; ardet in inmensum geminatis ignibus Aetna Parnasusque biceps et Eryx et Cynthus et Othrys, et tandem nivibus Rhodope caritura, Mimasque Dindymaque et Mycale natusque ad sacra Cithaeron. Nec prosunt Scythiae sua frigora: Caucasus ardet Ossaque cum Pindo maiorque ambobus Olympus aeriaeque Alpes et nubifer Appenninus. Tum vero Phaethon cunctis e partibus orbem adspicit accensum nec tantos sustinet aestus, ferventesque auras velut e fornace profunda ore trahit currusque suos candescere sentit; et neque iam cineres eiectatamque favillam ferre potest calidoque involvitur undique fumo, quoque eat, aut ubi sit, picea caligine tectus nescit et arbitrio volucrum raptatur equorum. |

Phaethon loses control of the horses. . .There is a place where the scorpion curves his arms into twin bows and with his tail and with his arms on either side stretches his limbs over the space of two constellations. When the boy sees how, moist with the sweat of black venom, he threatens to wound him with the spear of his curving tail, bereft of his mind from icy fear, he drops the reins. The horses, when they feel the slack reins lying on their backs, break free from their course, and with no one holding them back, enter the air of an unknown region. Wherever impulse drives them they rush that way without direction, and they bump into stars fixed beneath the high ether, snatching the chariot along pathless ways. And now they aim for the heights, and now headlong by steep paths they are carried closer to the earth. the Moon wonders at the sight of her brother's horses running beneath hers, and how the clouds, on fire, are smoking. The highest places catch fire, and the earth splits into cracks and dries up, the moisture gone. The grasslands turn to white ash, the tree burns along with its leaves, the dry crops provide fuel for their own destruction. But I complain of small things. Great cities perish with their walls, fires turn entire civilizations, with their people, to ashes. The forests burn along with the mountains, Athos and Taurus and Cilix and Oeta burn, and so does Ida, now dry, formerly filled with springs, and Helicon of the virgins [i.e. the Muses] and Haemus, not yet named for Oeagrus; And so does Parnassus with its two summits and Eryx and Cynthus and Othrys, and Rhodope finally losing its snows, and Mimas and Dindyma and Mycale and Cithaeron born for sacred rites. Nor does her chill help Scythia; Caucasus burns and Ossa with Pindus and Olympus, which is greater than both, and so do the Alps, high in the air and the cloud-bearing Appenines. Then indeed Phaethon sees the world on fire on every side, and cannot endure such great heat, and he breathes in hot blasts of air as from a deep furnace and feels the chariot becoming white hot; and he cannot bear the ashes and the embers cast off and he is shrouded in hot smoke. Covered in pitch darkness he does not know whither he is going or where he is, and is carried along at the will of his flying horses. . . . |

Helios in his chariot, driving his horses, on a marble sculpture from the temple of Athena, Ilion, 3rd or 4th century B.C. Discovered by Heinrich Schliemann in 1874, this piece is now in the Pergamon-Museum in Berlin. (Illustration from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890).

Quotation for October, 2019

Lar Statuette, Andalusia, 1st cent. AD

For Halloween, Roman Lares and Lemures as Spirits of the Dead |

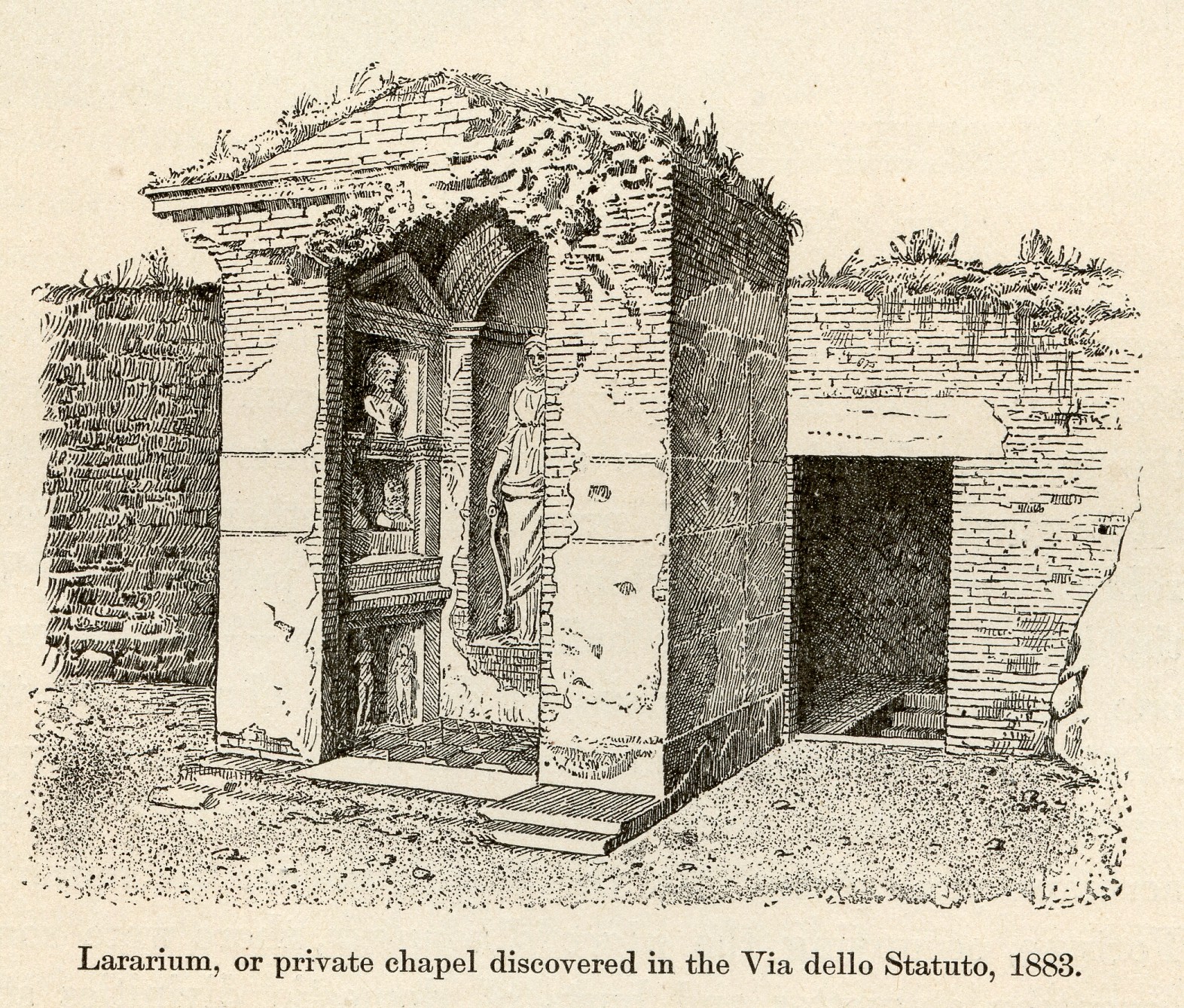

Above: A household shrine, or Lararium, belonging to a house discovered in Rome in December, 1883, during construction of the Via dello Statuto, between the Piazza Vittorio Emmanuele, on the Esquiline, and the Via Cavour in the Subura. Illustration from Rodolfo Lanciani, Ancient Rome, in the Light of Recent Discoveries, 1898.Top: Bronze figure of a Lar, between 1 and 50 A.D., in the National Archaeological Museum of Spain, photographed by Luis García (Zaqarbal), 3 December 2008 (via Wikimedia).

Ancestors and ghosts: the Roman Lares

It's Halloween season, when we gasp and scream at horrifying visions of the walking dead. Halloween is literally "All Hallows' Eve," the night before All Saints' Day on November 1, which is followed on November 2 by All Souls' Day, or the Day of the Dead, when we remember and revere the souls of family members and others who have passed on.

This month we salute the Roman Lares, household protective spirits, of individual families or even of neighborhoods or entire communities. The name "Lar" seems to be derived from the Etruscan word for "Lord," and these divinities may have their origins in the spirits of ancestors. A family would have at least one Lar figure, housed in a shrine along with figures of the Penates, household deities particularly associated with the storeroom and food supply. For a family of limited means, the shrine might just be a little wall niche; for a wealthy family, it could be an elaborate structure like the one illutrated at the top of this page. At meals or banquets, the Lar figures could be brought out to the table, where they could oversee the meal. They were also witnesses at events like marriages and births. Offerings were regularly made to the Lares, consisting of honey cakes, garlands of grain, fruits, incense, and the like.

Lares as community guardians

There were Lares of a more public nature, too. The Lares Compitales, or Lares of the compitum, or crossroads, were given shrines at crossroads, or the place where two or more roads meet. These guarded an entire neighborhood. Other Lares included the Lares Praestites, or Lares of the City, Lares Rurales, or guardians of the rural fields, the Lares Augusti, or Imperial Lares, and the Lares Grundules, or "Grunting Lares," said to have been given an altar and cult by Romulus (or Aeneas) when a sow miraculously gave birth to thirty piglets, but also associated with the grundae, or eaves of the house.

The Lares as plebeian deities

The Lares, as gods of the people, were distinctly plebeian in their cult, as opposed to the major gods. Their cult officials included slaves and freedmen, otherwise excluded from religious administration.

Despite Christian attempts to stamp out pagan religious practices, unofficial cults of the Lares persisted at least until the fifth century A.D.

Lemures as malevolent ghosts

If the Lares are protective ancestor spirits, the Lemures are their evil twins. The Lemures, also called larvae, were the vengeful unquiet spirits of the dead, such as those who had not received proper burial. They could be propitiated by walking barefoot at midnight and throwing black beans behind one. The Lemures would feast on these beans. The Lemures had a festival, the Lemuria, which took place in May, thus rendering May an unlucky month.

Plautus' Aulularia: The Lar speaks

In the play Aulularia of Plautus (ca. 254-184 B.C.), we get to meet an actual Lar, who begins the play with a Prologue in which he introduces the action to come. As the Lar explains, Euclio, an old man, has inherited his house from his father, who had inherited it from his own father. The grandfather was a miser, who, although he owned a little pot (aulula) containing a treasure of gold, never told his son about it, but buried it beneath the hearth, entrusting his secret to the household Lar, who was to tell no one. The son was left a farm with a few fields, which were barely enough to live on. The Lar hopes that the son will be less miserly, especially toward the Lar himself, but he is as stingy as his father, and so the Lar "gives as good as he gets, and so the man dies." The son, in turn, has his own son, the present owner, Euclio, but he is stingy, too. Euclio, however, has a daughter, Phaedria, who is nice, and gives prayers and offerings to the Lar, so the Lar reveals to Euclio the location of the treasure, so that he can provide a nice dowry for her. Phaedria, meanwhile, has become pregnant by a young man whom she met at a festival of Ceres, whose identity she does not know. The Lar arranges for the old gentleman who lives next door to ask the girl's hand in marriage. This old gentleman happens to be the uncle of Lyconides, the young man who got Phaedria pregnant. The text of the play is incomplete, but existing plot summaries seem to say that after several more plot complications, Euclio gives the gold to Lyconides, and he and Phaedria marry.

Below, in Latin and English, is the Prologue to Plaurus' Aulularia, spoken by the Lar of the household.

Plautus Aulularia vv. 1-39PROLOGUS LAR FAMILIARIS Ne quis miretur qui sim, paucis eloquar. |

I am the Lar, and I know where the gold is hiddenPROLOGUELar Familiaris:

That no one may wonder who I am, I shall explain briefly. |

Altar of the Lares Compitales, Pompeii. From Seyffert's Dictionary of Classical Antiquties, 1899, p.343.

Quotation for September, 2019

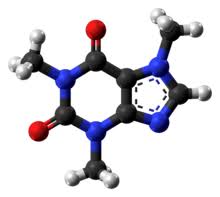

Caffeine molecule

To Celebrate the Sesquicentennial of the Periodic Table, Empedocles on the Four Elements |

Above: The Periodic Table of Elements, from Wikipedia. Top: Model of a caffeine molecule, made of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen (C8H10N4O2).

The Year of the Periodic Table, 2019

2019 is the sesquicentennial, or 150th anniversary, of the publication of Dmitri Meneleev's Periodic Table of Chemical Elements, the chart that hangs on the wall of just about every chemistry classroom. 2019 was therefore proclaimed the "International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements (IYPT2019)" by the United Nations General Assembly and UNESCO.

There had been many previous lists of groupings of elements by various scientists. One of the earliest was by Antoine Lavoisier (1789). The version by the Russian Mendeleev, which came to be considered the canonical version, was first published in February, 1869. Elements are listed according to atomic weights (the number of protons in the nucleus), number and configuration of electrons, and chemical properties such as whether they are gases, metals, or non-metals. Importantly, gaps were left for elements as yet unknown. Some of these are now filled in, with elements either discovered or, in some cases, synthesized.

Although February is the actual publication date of Mendeleev's table, celebrations of the event have been taking place all year during 2019. For example, on September 24, a macramé version of the Periodic Table went on tour at various locations in Europe.

A periodic table of molecules is proposed

The question has been raised of whether there can be a periodic table for molecules as well as for elements. In September, 2019, a research team from the Tokyo Institute of Technology suuggested an approach to such a table. For some elements, when they form clusters with a symmetrical shape, the outer, or valence electrons, which interact with other elements to form compounds, act like the electrons of individual atoms. This research can lead to the development of new materials.

What is the world made of?

Philosophers and scientists (which used to be the same thing) have always been fascinated by the question of what the world (and the universe) are made of. Not only in ancient Greece and Babylonia, but in Persia, Japan, Tibet, and India, lists were made of the primal elements, generally some variation of Earth, Air, Water, and Fire, sometimes with the addition of "Aether" or "Void." The Chinese Wu Xing system lists Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water.

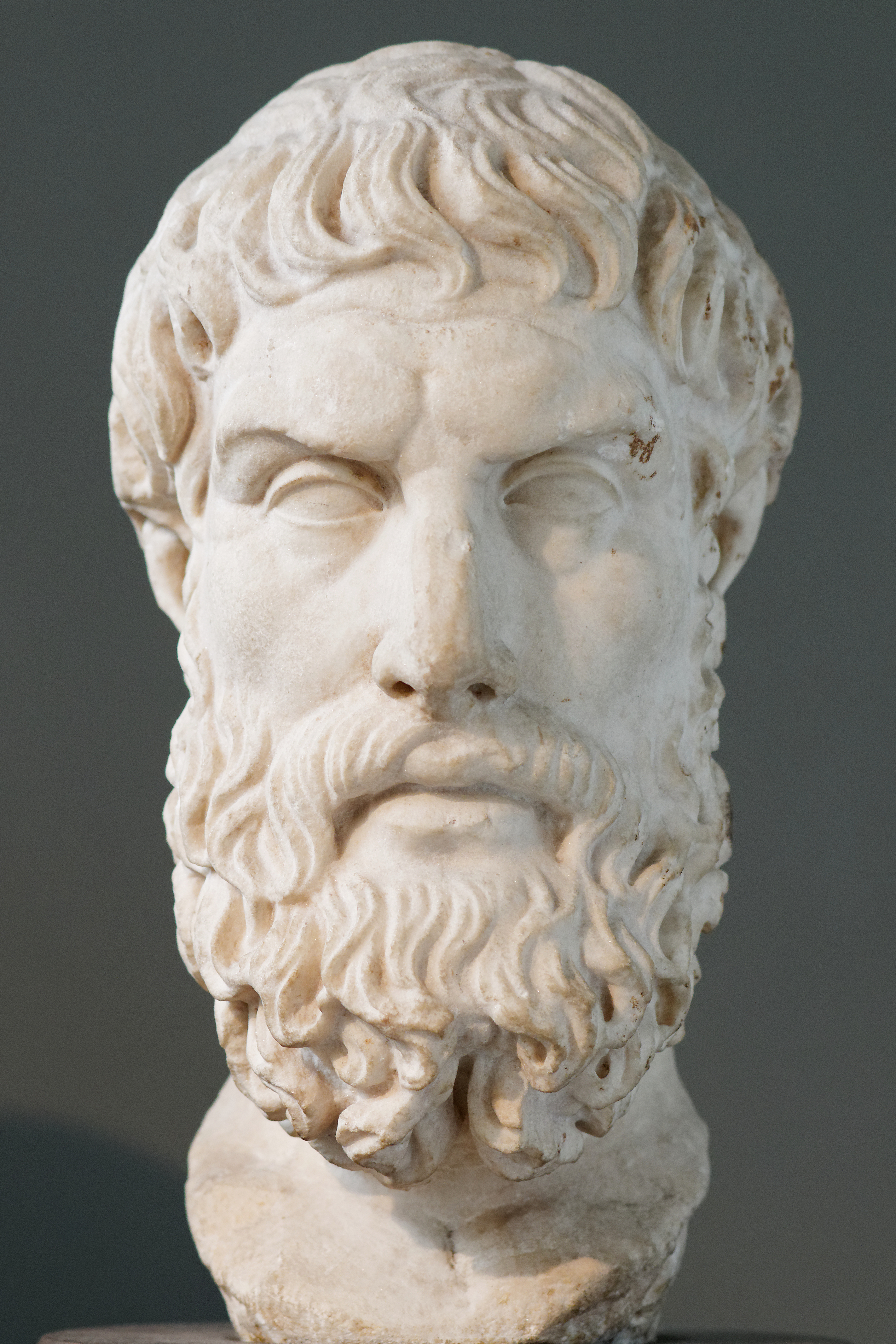

Empedocles (ca.494 B.C. - 434 B.C.), from Acragas, Sicily, a Pre-Socratic philosopher, was the first Greek to systematize the theory of the Four Elements, Earth, Air, Water, and Fire. Ancient Acragas is today Agrigento, and the nearby harbor is named Porto Empedocle in his honor.

Around the same time, a somewhat younger contemporary, Democritus of Abdera, Thrace (ca. 460 B.C. - 370 B.C.) was proposing the first formulation of an atomic theory, developed with his mentor Leucippus.

Empedocles and the four elements

Empedocles was the last Greek philosopher to write in verse. His principal work, On Nature (Peri Phuseos) exists only in fragments, including pieces of papyrus. He was friendly with the Pythagoreans, and was said to have been a brilliant orator. One of his students was the orator and rhetorician Gorgias. Stories were told of him, some undoubtedly apocryphal, including a tale that he died by leaping into the boiling crater of Mount Aetna.

The elements, he wrote, were constantly being united by Love (Philotes), also called Aphrodite, to make the materials of the world, and conversely being pulled apart by Strife (Neikos) into their constituent elements.

We have chosen an excerpt from one of the fragments that lays out this theory as our Quotation of the Month.

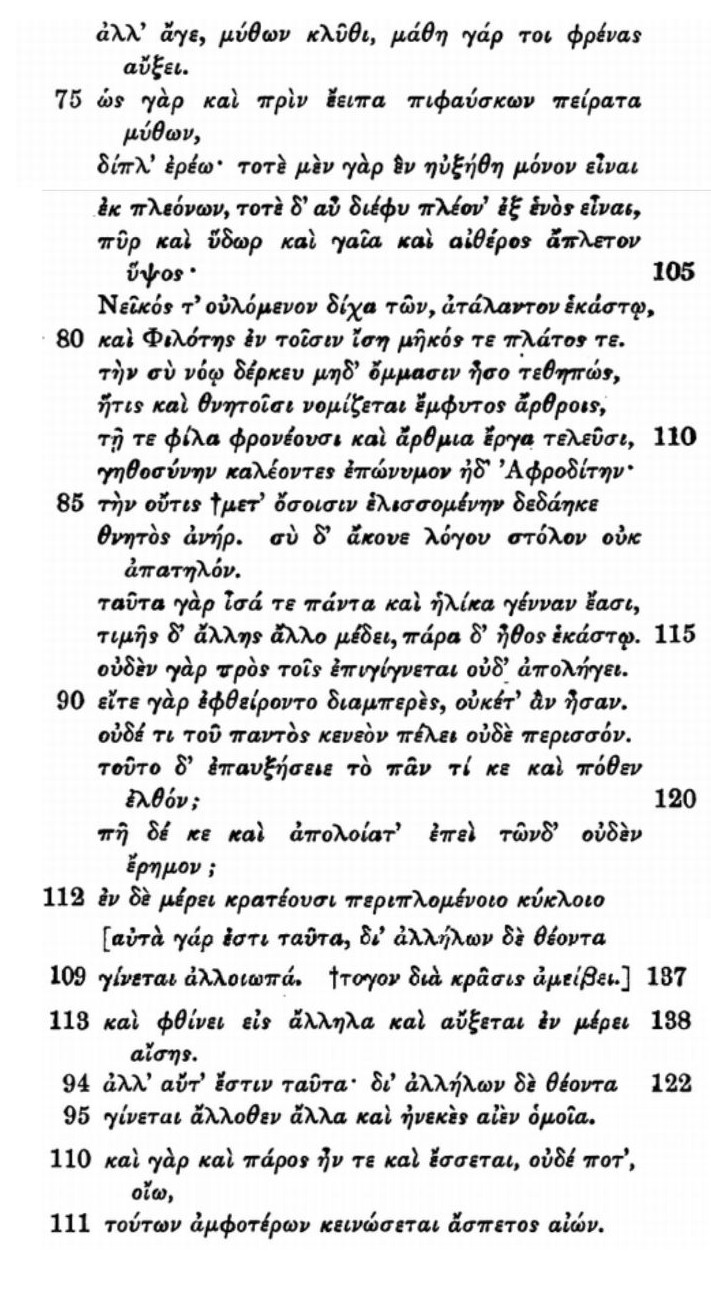

Below, in Greek and English, is a passage from the work of Empedocles, On Nature. The text, and a translation by Arthur Fairbanks, are from The First Philosophers of Greece, Fragments of Empedocles, Book I, 1898, as scanned by the Hanover Historical Texts Project. Some lines (bracketed) repeat other lines, and the editor/translator moved some other lines around, hence the numbering on those lines is out of sequence.

Empedocles, Fragment from Book I

|

Earth, air, water, and fire form and reform, guided by Aphrodite74. But come, hear my words, for truly learning causes the mind to grow.75. For as I said before in declaring the ends of my words: Twofold is the truth I shall speak; for at one time there grew to be the one alone out of many, and at another time it separated so that there were many out of the one; fire and water and earth and boundless height of air, and baneful Strife apart from these, balancing each of them, and Love among them, their equal in length and breadth. 81. Upon her do thou gaze with thy mind, nor yet sit dazed in thine eyes; for she is wont to be implanted in men's members, and through her they have thoughts of love and accomplish deeds of union, and call her by the names of Delight, and Aphrodite; no mortal man has discerned her with them (the elements) as she moves on her way. But do thou listen to the undeceiving course of my words. . . 87. For these (elements) are equal, all of them, and of like ancient race; and one holds one office, another another, and each has his own nature. . . . For nothing is added to them, nor yet does anything pass away from them; for if they were continually perishing they would no longer exist. . . . Neither is any part of this all empty, nor over full. For how should anything cause this all to increase, and whence should it come? And whither should they (the elements) perish, since no place is empty of them? And in their turn they prevail as the cycle comes round, and they disappear before each other, and they increase each in its allotted turn. But these (elements) are the same; and penetrating through each other they become one thing in one place and another in another, while ever they remain alike (i.e. the same). 110. For they two (Love and Strife) were before and shall be, nor yet, I think, will there ever be an unutterably long time without them both. |

Empedocles, in Thomas Stanley "History of Philosophy," 1655.

Quotation for August, 2019

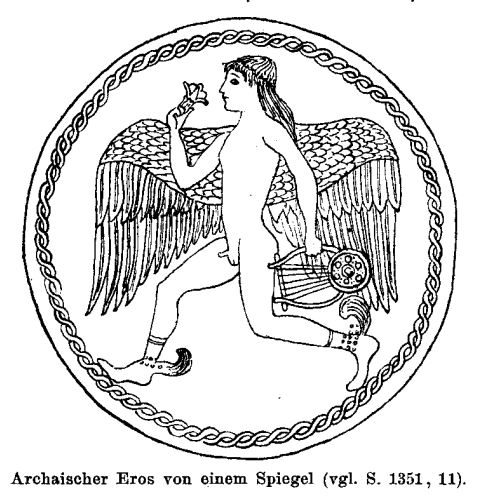

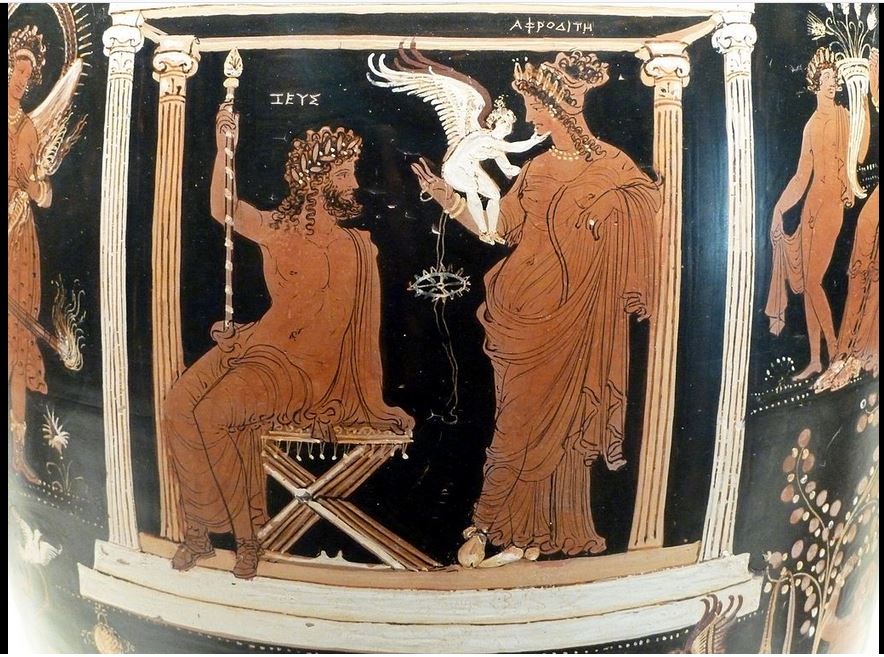

Eros

For Women's Equality Day: The Poetess Corinna tells of the Marriages of the Daughters of Asopus |

Above: Apuleian vase painting of Zeus plotting with Aphrodite to seduce Leda, while Eros sits on her arm (ca.330 B.C.). Getty Villa Collection, photo by Dave Hill and and Margie Kleerup, December 27, 2010, via Wikimedia.Top: Eros, on an archaic mirror. Image from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.

The 19th Amendment is ratified and certified

On August 26, Women's Equality Day is celebrated in the U.S., commemorating the adoption, in 1920, of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees women the right to vote. The designation was first established by a resolution of Congress in 1973, and is proclaimed each year by the President of the United States. (The 19th Amendment was actually declared ratified on August 20, but was not certified by the Secretary of State until August 26, so August 26 was chosen as the date of the commemoration.) The proclamation was first issued by President Nixon, and has been made by every president since then, including President Trump. Ironically, no woman President has yet declared Women's Equality Day.

Our Quotation of the Month will be from a poem by one of the women poets of ancient Greece, Corinna of Tanagra in Boeotia.

Yes, there were women poets besides Sappho

There were a number of women poets in ancient Greece, of whom the best known is Sappho of the island of Lesbos. Her name and home island have given us the words "Sapphic" and "lesbian," although, of course, that place was in reality by no means an "island of women." Its other most famous author was the lyric poet Alcaeus, whose muscular lyric poetry contrasts with that of Sappho. We are lucky that so much of Sappho's poetry survives, thanks to quotations in other writers and in scraps of papyrus.

But there were others, whose names alone survive, or whose compositions are known from a few lines here and there in comments of other writers or scholiasts. These include Myrtis of Anthedon in Boeotia (6th century B.C.), the teacher of fellow Boeotians Corinna and the great lyric poet Pindar of Thebes. They include also Praxilla of Sicyon, on the Gulf of Corinth, who flourished in the 5th century B.C. Of others even less is known, except for names here and there.

Of Corinna we know a bit more. Her dates are uncertain, but tradition has it that she competed with Pindar in a singing contest — and won! This would put her in the late 6th or early 5th century B.C.

Corinna's surviving poems

Corinna composed in her native Boeotian dialect, a form of Aeolian Greek, rather than the more literary Attic or Athenian Greek or the Doric used by other lyric poets. Many of the short quotations attributed to her are from grammarians interested in her use of language.

Two extended fragments of the Corinna's poems survive, contained in much mutilated and emended papyrus fragments discovered in Egypt. In one of these, the "Contest Between Helicon and Cithaeron," the two Boeotian mountains participate in a singing contest. Cithaeron wins the contest, and an angry Helicon causes a great landlside, which buries the town at the foot of the mountain. This poem was used as the Quotation of the Month for March 2012 for Women's History Month. The poem and discussion can be found there.

The second fragment is from the poem "The Marriages of the Daughters of Asopus."

The Marriages of the Daughters of Asopus

In the "The Marriages of the Daughters of Asopus," the daughters of the river god Asopus have all been abducted or seduced by major gods, Zeus, Poseidon, Apollo, and Hermes. Asopus is, naturally, upset, and wants to know what has become of his daughters. In the fragment that we have, the seer Acraephen, otherwise unknown in mythology, tells Asopus not to worry, all his daughters are now wed to great gods and will give birth to great heroes. Three are wed to Zeus, three to Poseidon, two to Apollo, and one to Hermes. The beginning, in which the names of the daughters are given, and the end, in which Asopus acquiesces to the arrangement, are known only in references and mutilated bits of the papyrus.

There were many versions of the story, told by different poets. Pindar alludes to the myth in his eighth Nemean Ode. The number of daughters varies in the different versions. Corinna mentions nine, and damaged fragments give the names of nine: Aegina, Thebe, and Plataea abducted by Zeus, Corcyra, Salamis, and Euboea abducted by Poseidon; Sinope and Thespia abducted by Apollo, and Tanagra abducted by Hermes. Diodorus Siculus gave Asopus twelve daughters and Apollodorus says he had twenty daughters.

A complicated story

The first thing one notices about these names is that all are names of cities. The next thing is that they are all over the map, located in different parts of the Greek world, unlikely to be associated with one river. For example, Thebe (eponymous nymph of the city of Thebes in Boeotia), is the twin of Aegina, an island off the coast of Attica. Corcyra (Corfu) is an island off the west coast of Greece. One explanation lies in the fact that there were actually five different rivers named Asopus, one in today's Turkey and four in Greece: one in Boeotia, one near Corinth, one in Thessaly, and one in Corfu. Other explanations are political. The city state of Aegina was a maritime power before Athens was a great power, and was allied with Thebes against Athens in the early years of the Persian Wars. The political and mythological alliances as well as poetic influences involved in the stories of the daughters of Asopus are too complicated to go into here. Suffice it to say that it gets very convoluted! An excellent reference is to be found in Chapter 1 by Gregory Nagy of Aegina: Contexts for Choral Lyric Poetry. Myth, History, and Identity in the Fifth Century BC (ed. David Fearn; Oxford 2011) pp. 41-78, available online as Asopos and his multiple daughters: Traces of preclassical epic in the Aeginetan Odes of Pindar.

The other thing that one notices is that the daughters themselves do not seem to have been asked their opinion of any of these goings on. Marylin Skinner, in "Corinna of Tanagra and her Audience" (Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature 2 (1), 1983) observes that Corinna, although a woman, tends to compose stories from a masculine point of view.

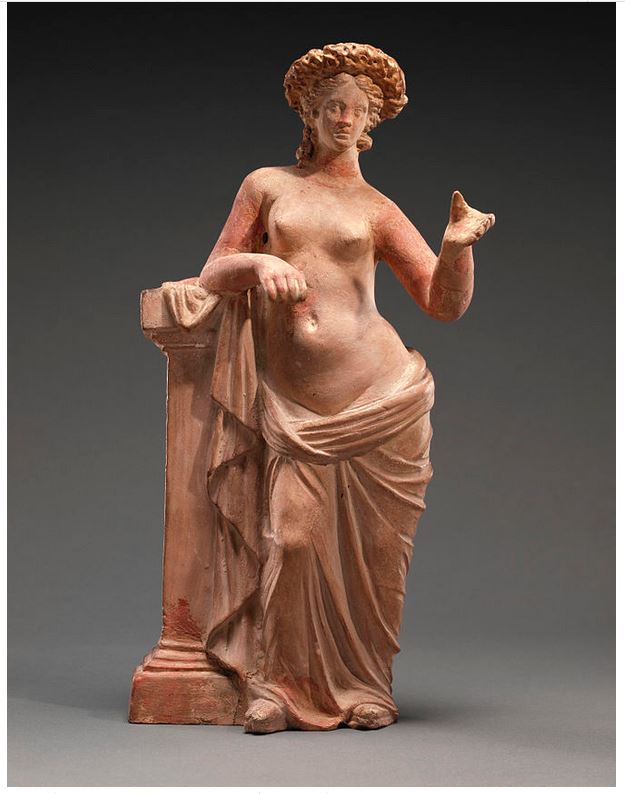

An ancient critic's opinion

Pausanias, in his travels through Boeotia (Paus. IX.22.3) tells us that Corinna's tomb was in her native Tanagra, "in a conspicuous part of the city." In the gymnasium was a painting of her, depicting her as very beautiful. In the picture she is binding her head with a fillet for her victory over Pindar at Thebes. With regard to her victory, Pausanias shows a clear preference for the male singer, who furthermore had ditched his provincial dialect for the more literary Doric. Pausanias voices the opinion that her defeat of Pindar had less to do with her poetry than with her use of the Boeotian dilaect, "which the Aeolians could understand," and with her good looks, since "she was the most beautiful woman of her time, if we can believe the painting." Meow!

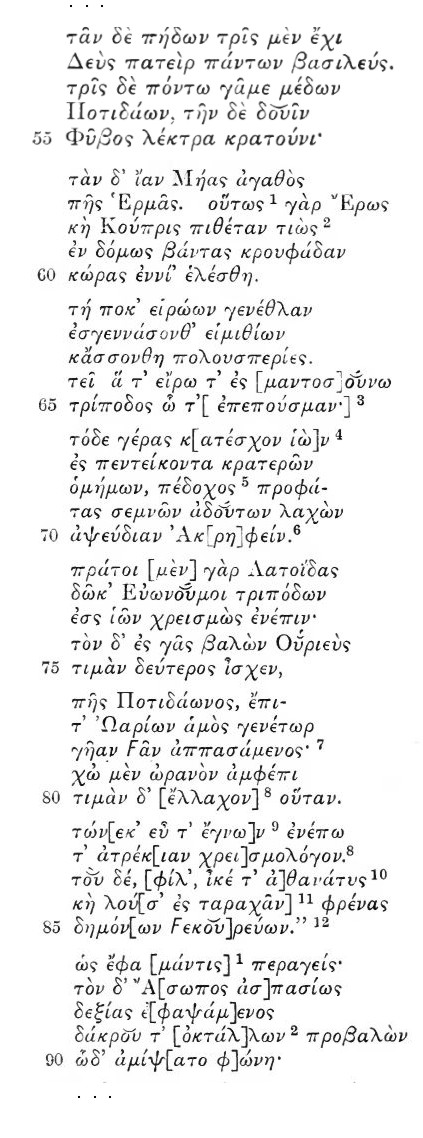

Below, in the Aeolic Greek of Corinna's native Boeotia and in English, is the only extended fragment (Fragment 33) of Corinna's poem about the marriages of the daughters of Asopus. I have used the Loeb edition of the text, edited by J.M. Edmonds (1927), together with Mr. Edmonds' translation. In these verses, the seer Acraephen tells Asopus about the marriages of his daughters. (I have omitted a few mutilated lines at the beginning and end of the fragment, which would have filled out the story.) While I have made no changes to Edmonds' prose translation, I have divided it into lines corresponding to the verses in the Greek text.

Corinna, Fragment 33

|

The seer Acraephen tells Asopus of the marriages of his daughters. . .Of thy daughters, three are with Father Zeus the king of all, three are wedded to Poseidon lord of the sea, two do share the bed of Phoebus, and one is wife to Maia's good son Hermes. For them did Love and Cypris persuade to go secretly to thy house and take thy daughters nine. and they in good time shall bear thee a race of demigod heroes, and be fruitful mothers of children. Learn thou both the things thou didst ask of the oracular tripod, and how it is I learnt them. This honour have I of fifty mighty kinsmen, the share allotted Acraephen in the holy sanctuary as foreteller of the truth. For the son of Leto gave the right of speaking oracles from his tripods first unto Euonymus; and Hyrieus it was who cast him out of the land and held the honour second after him, Hyrieus son of Poseidon; and my sire Orion took his land to himself and had it next, and now dwells in heaven — that is his portion of honour. Hence it comes it that I know and tell the truth oracular. And as for thee, my friend, yield thou to the Immortals and set thy mind free from tumult, wife's father to the Gods. So spake the right holy seer, and Asopus grasped him heartily by the hand, and dropping a tear from his eyes thus made him answer . . . |

Tanagra statuette of Aphrodite (10.6"), ca.250-200 B.C., Getty Villa Collection. Photo via Wikimedia. Tanagra, Boeotian home town of Corinna, became famous in later times (from the later fourth century B.C. onwards) for its mass-produced, mold-cast terracotta figurines.

Quotation for July, 2019

For the Anniversary of the Moon Landing: Anaxagoras Determines the Moon's True Nature and is Parodied by Aristophanes |

Above: "Man's First Walk On The Moon," No. 6 in a package of twelve photo prints taken from official NASA films, A Mike Roberts Color Production, 1969. Top: Anaxagoras, as depicted in the Nuremberg Chronicle, a history of the world, printed in both Latin and German editions in Nuremberg in 1493, with woodcut illustrations.

Science praised and derided: the 1969 Summer Institute on Computers and Classics

In July, 1969, my husband John and I participated in the Summer Institute in Computer Applications to Classical Studies, held at the University of Illinois, in Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, by the American Philological Association (now the Society for Classical Studies). A description of the Summer Institute appears above on this page, with links to the final report of its activities submitted to the National Endowment for the Humanities. John, mathematician and computer expert, was an instructor and I was a participant, learning programming in FORTRAN and how to use a keypunch to prepare the bulky IBM punched cards. I eventually prepared boxes and boxes of cards containing all the text of the Homeric Hymns and the poems of Hesiod for my project of studying the use of mythic themes in oral poetry.

Although Biblical scholars had been experimenting with using primitive accounting machines for studying the Scriptures since the 1940's, the idea that computers could add anything to our understanding of literature was widely derided among academics, and computer applications were not considered "real scholarship." (Most of us who didn't already have tenure didn't get it!) Attitudes have changed, fortunately.

A magical moment, as we watched the moon landing

As befitted our scientific enterprise, on July 20, 1969, we joined students and faculty and other members of the UIUC community in the university gymnasium to watch on the big screen as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to walk on the moon's surface. As we watched the low-definition, dreamlike images from the live transmission, it was a truly magical moment, bringing us all together in a communal experience. (The Woodstock Music Festival, another communal experience, would take place later that same summer.)

Anaxagoras leads a scientific revolution in ancient Athens

The moon landing was a product of the Scientific Revolution, which began in the Renaissance, and the Industrial Revolution, which comes to us out of the 19th century. But there was an earlier Scientific Revolution in ancient Greece, whose rediscovery led to the development of modern science. Thales of Miletus (ca. 624/623-ca. 548/545 B.C.) mathematician and astonomer, who applied deductive reasoning to the solution of geometrical problems, may be considered a founder of ancient science. Other pre-Socratic philosophers followed, including Anaximander, Anaxagoras, and Democritus, a proponent of the atomic theory.

Anaxagoras (ca. 510-ca. 428 B.C.), who lived in Athens, became particularly associated in the public mind with science, both appreciated and derided in the popular mind. He influenced Euripides, and may have influenced Democritus. He was a friend of Pericles, the powerful Athenian general and leader during the heyday of the Athenian Empire and the early Peloponnesian War with Sparta (he died of the plague in 429 B.C., two years into that disastrous war). Anaxagoras was later charged with impiety for saying that the gods did not exist, and that the sun was a blazing mass of metal, that the earth was a rock, and the moon a piece of earth. He correctly said that the moon shines by reflected sunlight.

No complete writings of Anaxagoras remain, only fragments and the comments of others. He apparently believed that everything is made up of combinations of the same elements, and that the overriding principle of the universe is nous, or "Mind," which controls the entire cosmos. He believed that everything is in rotation. He seems to have believed that there might be multiple worlds, but also believed that the earth was flat.

Anaxagoras was forced into exile in Lampsacus, on the Hellespont, where he died. It is surmised that his punishment was due less to his ideas than his association with Pericles, and and was an act of revenge by Pericles' enemies.

Anaxagoras, Socrates, and Aristophanes

Socrates, too, was put on trial for impiety, for not believing in the gods of the state, as well as for corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens, and was put to death. Socrates' death, described in Plato's Apology, occurred in 399 B.C., and Anaxagoras, though long gone, figures prominently in the dialogue. Meletus, Socrates' accuser, says that Socrates does not believe that the sun and the moon are divinities, but that the sun is a stone and the moon earth. Socrates answers that he is not an atheist, saying, "Who do you think you are accusing, Anaxagoras?", and goes on to explain that the views of Anaxagoras are readily available in books, not to mention on the popular stage, and that anyone can laugh at these views, if they are thought to be those of Socrates.

The allusion to the stage is aimed, among others, at Aristophanes, whose depiction of a cartoon Socrates, spouting gobbledegook cribbed from Anaxagoras, in his comedy the Clouds, makes it still one of the playwright's funniest plays.

A cartoon Socrates in a swinging basket

In the Clouds, Strepsiades is being bankrupted by his son Pheidippides, who spends all his father's money on horses, which he races. Strepsiades wants his son to enroll in the Phrontisterion, or Thinkery, run by Socrates, so that he can learn how to use Worse Logic (as opposed to Better Logic) to prove an unjust argument and get his father out of debt. Pheidippides refuses, and so Strepsiades goes to school in his place.

A student takes Pheidippides around, showing him other students whose noses are in the ground (studying what is below the earth) while their upturned backsides are "studying astronomy on their own." Socrates himself appears dangling from a basket, where he contemplates the sun as he "suspends judgment" in order to learn about the cosmos. Throughout the play, various scientific theories of Anaxagoras and others are parodied, including the Vortex (dinê), which keeps everything rotating, replacing Zeus. In the spirit of scientific inquiry, "Socrates" has also determined that a gnat buzzes by using its anus as a trumpet.

Extra humor is injected into the proceedings by Strepsiades' continual common-sense interpretations of high-falutin' scientific jargon. For instance, when the students are looking for things beneath the earth, he assumes that they are looking for edible lily bulbs. When they say they are studying geometry, he assumes that they are dividing up land to allot to Athenian citizens, and when shown a map that includes Athens, he says, "That can't be Athens, there are no law courts!" Finally Pheidippides, the son, joins the Thinkery and uses the Worse Logic to prove that a son may beat his parents, whereupon Strepsiades burns the whole place down.

Below, in Greek and English, is a selection from Aristophanes' parody of Anaxagoras' and other pre-Socratic philosophers' scientific inquiries, which he attributes to a cartoonish "Socrates."

Aristophanes Clouds 181-239

|

Students have their backsides in the air, Socrates is suspended in a basketSTREPSIADES: ... Open, open quickly the Thinkery,and, as quickly as possible, show me Socrates. For I want to become a student. But open the door! — O Heracles, what kind of beasts are these? STUDENT: Why do you act surprised? What do they seem like to you? STR: They seem like those whom we brought from Pylos, the Spartans. But why do they fix their eyes so on the ground? STU: They search for what is beneath the earth. STR: Of course! They are looking for edible bulbs. You, over there, don't trouble yourself about it. I know where there are big beautiful ones. But what are they doing that they stoop down so low? STU: They are searching in Erebus below Tartarus. STR: Why, then, is their backside looking at the sky? STU: It is studying astronomy on its own. But come inside, students, so that HIMSELF doesn't find us here. STR: Not yet, not yet! Let them remain so that I can share a little problem of mine with them. STU: But it is not good for them to spend too much time in the open air. STU: This is Astronomy. STR: And what is this? STU: Geometry. STR: Well then, what is it useful for? STU: To measure the earth. STR: Oh, for distributing land-grants [seized from enemy lands]? STU: No, but for the whole earth. STR: That is a fine thing you say, an ingenious device that is democratic and useful. STU: And here is a chart of the entire earth. You see it? Here is Athens. STR: What are you saying? I don't believe you, because I don't see any judges sitting. STU: In truth, that is Attic ground. STR: And where are my fellow-townsmen of Cicynna? STU: They're in there. And here's Euboea, as you see, stretched out at length, far off. STR: I know, pulled apart by us and Pericles. But where is Sparta? STU: Where is it? Right here. STR: How close to us! Please consider this, how to push it far away from us. STU: That isn't possible, by Zeus. STR: So much the worse for you, then. Hey, who is that man in a hanging basket? STU: HIMSELF! STR: Who HIMSELF? STU: Socrates. STR: O Socrates! [to the student] You there, call out to him loudly for me. STU: Call him yourself. I do not have the leisure. STR: O Socrates! O my little Socrates! STR: First of all, what are you doing, please tell me? SOC: I walk on the air and contemplate the sun. STR: Then you look down on the gods from a wicker basket and not from earth (if you do look down on them). SOC: I could never have correctly discovered celestial matters without suspending judgement and mixing my subtle thought with the air that is like it. If on the ground I had observed things above from below, I would never have found them. For the earth by its force draws to itself the humours of one's thought. The same thing happens to the cardamom plant. STR: What are you saying? Thought draws the humours into the cardamom? Come down now, my little Socrates, to me, so that you can teach me those things that I came for. SOC: What did you come for? STR: I want to learn to speak . . . |

"Africa and Portions of Europe and Asia As Seen From Apollo 11," No 10 in the same series of photographs from NASA sources as the picture of the astronaut above. So here, having looked at space from the point of view of the ancient world, we see what the ancient world looks like from space!

Quotation for June, 2019

Trade With China — The Ancient Silk Road, as Known to the Greeks and Romans: Vergil's Georgic II vv.109-139 |

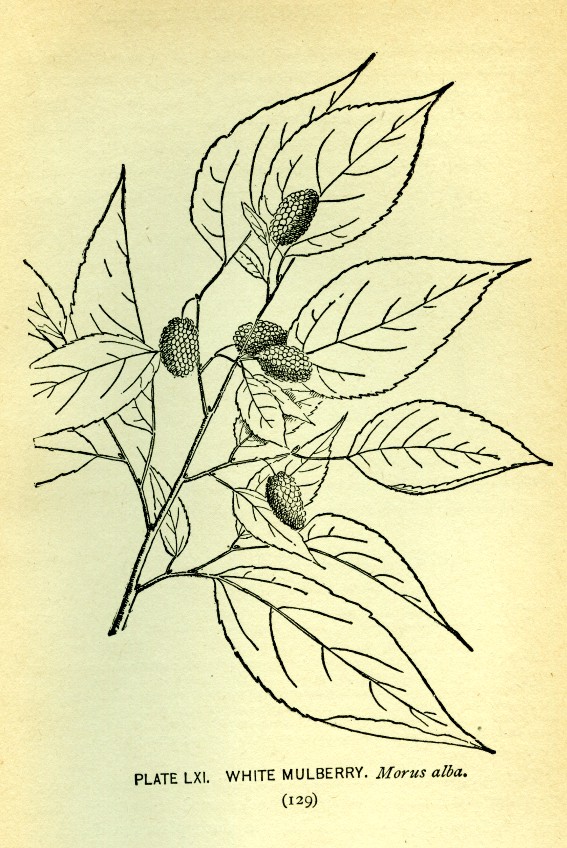

Above: This is what happens when women wear silk dresses! The Romans attempted to ban the wearing of silk, as being too revealing and therefore immoral, not to mention a drain on the economy. Illustration by Edith Follet for Ovide, l'Amour, l'Art d'Aimer, Paris, Éditions Nilsson, 1920's. Top:White mulberry leaves, the favorite food of the silkworm, illustration by Mrs. Ellis Rowan for Alice Lounsberry, A Guide to the Trees,, 1900.

Trade between the West and China: an ancient network of routes

Trade between Western nations and China, economic imbalances, and ways of guarding proprietary technology are much in the news. Today the concerns are about soybeans in the Midwest and cybersecurity. But trade with China and the issues it raises are in fact thousands of years old. This month's Quotation of the Month is inspired by the ancient Silk Road, known to the Greeks and Romans, as well as to the people of Persia, India, and Egypt.

The Classical Silk Road was not just a single route, it was a network of routes that tied together the flow of all kinds of products between the Mediterranean and the Far East. It had both a land component and a maritime route that sent ships from China and southeast Asia around the Indian peninsula into Egypt and the Near East. Just so, today, the new Chinese Belt and Road Initiative sends freight by rail across Asia and over the sea by ship.

Predecessors of the Silk Road

The Silk road had many predecessors, proceeding from the Near East to India and from China westward. One of these predecessors was the famous Persian Royal Road, reorganized and rebuilt by Darius I (Darius the Great) in the 5th century B.C. The desciption of this service by Herodotus serves as a motto for the U.S. Post Office:

Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.By employing fresh riders and fresh horses at each relay (like the Pony Express), the couriers could deliver the royal mail from Susa, in Persia, to Sardis, in today's Turkey, 1677 miles (2699 km) in nine days, a journey that took ninety days on foot.

Alexander the Great and the Han Dynasty

Alexander the Great (356-325 B.C.) was one of the earliest Western travelers on the Silk Road, penetrating into Asia as far as India. In August 329 B.C. he founded the city of Alexandria Eschate ("Farthest Alexandria") in what is now Tajikistan. These were the first Greeks known to the Chinese, whose historical writings refer to them as the Dayuan ("Great Ionians"). The Chinese were known to the Greeks as the Seres ("Silk People") because that was their most famous and sought-after product. Strabo (63 B.C. - 23 A.D.) wrote that "The Greeks extended their empire even as far as the Seres and the Phryni."

The Silk Road proper was established during the Han Dynasty (207 B.C.-220 A.D.), being opened from China to the West in 130 B.C.

Misinformation about silk: does it grow on trees?

Just as today, nations have always attempted to keep secret their technological processes. The Greeks and Romans did not know exactly what silk was or what it came from. Weavers on the island of Cos imported raw (unprocessed) silk and wove it into a slightly inferior grade of cloth, but the finer quality material had to be imported from China.

A common misconception was that silk was a vegetable product, combed or scraped from trees. Nor were Westerners even sure where the "Seres" were located. There was an impression that they were somewhere to the east of the known lands, perhaps on the shore of some far eastern ocean. Horace, in his Odes, speaks of the Seres and Indians as a metaphorical reference to "way out there somewhere" (Horace Carmina 1.12.56, 3.29.27, 4.15.23).

Some understood that a little caterpillar was involved in the production of silk. It does indeed live on trees. Its favorite food is the leaves of the white mulberry. Silk is made of fibers from its cocoons. Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.) wrote in the chapter on insects in his Natural Histories (11.22.25 par.75 ff.) of the bombyx or silkworm that "These insects weave webs similar to those of the spider, the material of which is used for making the more costly and luxurious garments of females, known as 'bombycina'." He credits a woman of Cos, named Pamphile, with discovering the art of spinning this material.

In the reign of the Emperor Justinian, in the 6th century A.D., two monks, who had been preaching Christianity in India, were finally able to smuggle silkworms out of China, hidden in bamboo canes, and bring them back to the Byzantine Empire.

A ban on the wearing of silk at Rome

Silk became immensely popular during the Roman Empire. Its diaphanous nature, revealing the body in all its splendor, was seen as scandalous by some conservatives. There were several attempts by the Roman Senate to ban its wearing. Seneca the Younger (ca. 3 B.C.- 65 A.D.) proclaimed in one of his Declamations:

I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes. ... Wretched flocks of maids labor so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body.

There was also an economic reason for the ban. A tremendous amount of gold flowed out of the the Roman Empire to buy all that silk. This was a threat to the balance of payments!

Vergil contrasts the varying products of different countries — none as good as Italy

Vergil was among those Romans who believed that silk was a vegetable product, combed from the leaves of trees, In Book II of the Georgics, which is devoted to the culture of trees and vines, he speaks of how each kind of land, and hence each nation, is fitted to grow one kind of product. He ends by comparing all of them unfavorably with Italy! Our Quotation of the Month excerpts Vergil's catalog of foreign products — ebony from India, frankincense from the Sabaeans (Arabia), etc. When he gets to the Chinese he speaks of "how the Seres comb from leaves their fine fleeces."

Below, in Latin and English, is Vergil's catalog of products, in Georgic II.109-139. The text is from the Loeb edition, 1916, revised in 1999. Verse 129 perhaps does not belong here, as it is repeated in Georgic III.283.

Vergil Georgic II.109-139

|

All lands bear different products, but none compare with ItalyNor can all lands bear all products.Willows grow in rivers and alders in dense bogs, and on rocky hills the unfruitful ash; the shores are joyous with myrtle groves; and finally, Bacchus loves the open hills, yew trees the North Wind and cold. See how the globe is conquered by its most distant cultivators and the eastern homes of the Arabs and the painted Gelonians. Homelands are allotted to each tree. Only India bears black ebony, the frankincense bough belongs only to the Sabaeans. Why should I tell of the balsam dripping from the fragrant wood and the pods of the evergreen acacia? Why speak of the Ethiopian groves, white with soft wool, or how the Seres comb from leaves their fine fleeces? Or those groves that India, nearer the Ocean, bears, a bend in the ends of the earth, where arrows can scarcely surmount the air at the treetops? And that race is not slow in taking up the quiver. Media bears the bitter juice and clinging taste of the felicitous citron, than which nothing is more effective; if sometimes cruel stepmothers have infected the cup mixing herbs and not innocuous spells, relief comes and the black venom is driven from the limbs. The tree itself is large, very similar to a laurel (and if it did not throw out a different odor, it would be a laurel). The leaves fall in hardly any wind, but the flower holds on tenaciously. The Medes rinse their odorous mouths and breath with it and cure the asthma of the old. But neither the forests of the Medes, most wealthy land, nor the beautiful Ganges and the Hermus turbulent with gold can compete with the glories of Italy, not Bactria or India and all of Arabian Panchaea with its incense-bearing sands. . . . |

Illustration by Edith Follet for Ovide, l'Amour, l'Art d'Aimer, Paris, Éditions Nilsson, 1920's.

Quotation for May, 2019

For Spring Showers and Flowers: The Roman Festival of the Floralia, Complete With Weird Behavior, As Described by Juvenal's Satire No. 6 |

Above: Relief of Gladiatrices, or women gladiators, from Halicarnassus. Two women, Amazonia and Achillea, fight each other. Source, girlswithguns.org, via Wikipedia. Women gladiators were apparently a feature of the Floralia. Top: A modern interpretation of a gladiator's helmet.

The beginning of spring brings flowers and floods

"April showers bring May flowers." Thus goes the common saying, but this May brings more than flowers. It has brought severe floods to parts of the U.S., along with wind and tornados, delaying the planting of the usual spring crops that farmers depend on. In my neighborhood, the unremitting rain has brought an exuberant overgrowth of plants, trees, and grass, and an early infestation of biting insects, including the bane of my existence, the No-See-'Ums.

At the end of April and the beginning of May, the ancient Romans celebrated the arrival of Flora, an old Sabine goddess of spring, nature, and fertility. While considered a minor deity, she had her own flamen or official priest, and her own festival, the Floralia.

The Floralia, a licentious festival of Flora

The Floralia, or festival of Flora, took place from April 28 to May 3. This was a plebeian festival, as opposed to the more upright patrician observances. It was known for drinking, licentiousness, and generally weird behavior. There were mimes and naked dancers. Galba, who was briefly Emperor in 69 A.D., (the Year of the four Emperors) before he was assassinated, celebrated the Floralia, when he was still a praetor, with tight-rope-walking elephants (Suetonius, Life of Galba 6.1).

Another feature of the Floralia was the participation of female gladiators. Not that this was their only appearance. The participation of women in men's sports, including gladiatorial contests, is a little known phenomenon, which the authorities attempted to squelch, but was apparently very real.

The satirist Juvenal is shocked at women gladiators

Ovid, in his Fasti Book V vv. 183-378, has a long and light-hearted conversation with the goddess Flora herself in which they discuss the subject of the Floralia, but this month's Quotation of the Month comes from a more ironic source, Juvenal's Sixth Satire. This satire is mainly a long, misogynistic rant, in which he attacks all the supposed vices of women (including murdering their husbands), as well as the vices of men and corruption of society in general. But his description of female gladiators goes into some fascinating detail about the armor and behavior of these women, grunting and groaning as they practice their swordsmanship with heavy wooden swords against a wooden pole set up as a dummy competitor, wrapping themselves after sweaty practice in a woolen shawl, and rubbing their bodies with ceroma, a mixture of oil, wax, and clay used by wrestlers. Worthy of the Floralia, but they may be plotting a professional career! How awful, says Juvenal.

This satire is so salacious, it is omitted from some school editions of Juvenal.

Below, in Latin and English, is Juvenal's description of gladiatrices (Juvenal Satire VI.246-267).

Juvenal Satire 6.246-267endromidas Tyrias et femineum ceromaquis nescit, uel quis non uidit uulnera pali, quem cauat adsiduis rudibus scutoque lacessit atque omnis implet numeros dignissima prorsus Florali matrona tuba, nisi si quid in illo pectore plus agitat ueraeque paratur harenae? quem praestare potest mulier galeata pudorem, quae fugit a sexu? uires amat. haec tamen ipsa uir nollet fieri; nam quantula nostra uoluptas! quale decus, rerum si coniugis auctio fiat, balteus et manicae et cristae crurisque sinistri dimidium tegimen! uel si diuersa mouebit proelia, tu felix ocreas uendente puella. hae sunt quae tenui sudant in cyclade, quarum delicias et panniculus bombycinus urit. aspice quo fremitu monstratos perferat ictus et quanto galeae curuetur pondere, quanta poplitibus sedeat quam denso fascia libro, et ride positis scaphium cum sumitur armis. dicite uos, neptes Lepidi caeciue Metelli Gurgitis aut Fabii, quae ludia sumpserit umquam hos habitus? quando ad palum gemat uxor Asyli? |

Can you imagine the costume of such a woman?Who does not know about the Tyrian wool cloak and the wrestler's wax for women,or who has not seen the wounds on the practice-pole, which she hollows out with unremitting wooden sword and attacks with her shield, and goes through all her exercises, a matron fully worthy of the trumpet at the Floralia — unless in her heart she is plotting something more, and is preparing for the real arena? What modesty can a woman maintain, who wears a helmet, who flees from her sex? She loves strength. Yet nevertheless she does not want to become a man, for how small is our pleasure! What a pretty sight, if there were an auction of your wife's possessions, belt and gauntlets and crests and for the left leg, half-armor! or if a different branch of fighting moves her, you will be lucky if the girl sells her leggings. These are women who sweat even in a thin gown, whose delicacy even is burned by a short silk dress. See with what noise she strikes home the blows taught to her, and with what weight of the helmet she is bowed down, and in what a mass of bandages she settles upon her haunches, and laugh when, putting aside her armor, she takes up the drinking vessel. Tell me, granddaughters of Lepidus or blind Metellus or Fabius Gurges, what gladiator's wife ever assumed such a costume? When did the wife of Asylus groan at the practice-pole? |

"The Empire of Flora," by Tiepolo, ca. 1793, in the Fine Arts Museums of San Franciso, Legion of Honor, Gallery "E," given by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation. Photographer unknown.

Quotation for April, 2019

For Easter, Passover, Earth Day and Arbor Day, an Invocation to Diana by Catullus |

Above: Statue of Diana at the Huntington Art Gallery, San Marino, California, after the Diana of Versailles at the Louvre. In the original, she reaches over her shoulder for an arrow from a quiver strapped to her back. Photo by C.A. Sowa. Top: Artemis and deer, on a medallion of Antoninus Pius, from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890).

Celebrations of renewal

In April, four holidays were observed, each in its own way a celebration of renewal. Passover commemmorates the escape of the Jews from Egypt; Easter commemorates the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. On Arbor Day, we are encouraged to plant new trees, and Earth Day reminds us of the gifts of Mother Earth and our responsibility to protect her.

For our Quotation of the Month, we offer an invocation by the Roman poet Catullus to the goddess Diana, inhabitant and protector of sacred groves, women in childbirth, and young animals. She is a nature goddess, both huntress and nurturer, divinity of the moon in its revolving phases. The poem is No. 34 in the collection of Catullus' poems.

An invocation to Diana by Catullus

Catullus (ca. 84 - ca.54 B.C.) is best known for poems of a deeply personal nature, exposing his daily loves and hatreds, postings to the social media of his day. We learn of his love for the woman he calls "Lesbia" (real name "Clodia") and his falling out with her, of her love for her pet sparrow and her grief at its death. Some of his poems settle scores with rivals and other enemies, and one tells of his own heartfelt grief at the death of his brother —frater, ave atque vale. Catullus did write longer poems, such as No. 64, a little epic, or epyllion, on the marriage of Peleus and Thetis, into which is woven the story of Theseus and Ariadne (literally woven, describing the embroidered covering on the marriage couch of Thetis). The poems are written in a variety of lyric and other metres, suited to the subject matter of each poem. No. 64 is written in the dactylic hexameter of epic song.

The poem to Diana stands out as a different type from his usual subject matter, a formal invocation to a goddess apparently intended to be sung at an actual festival.

A celebration of Diana's many aspects

Diana is a goddess of many aspects. She is originally an ancient Latin goddess, whose primary sanctuary was a grove overlooking Lake Nemi, a small volcanic lake 19 miles south of Rome, often called "Diana's Mirror" (Speculum Dianae), site of her festival, the Nemoralia (from nemus, "grove"). Later, she was merged with the Greek goddess, Artemis, and her parents Jupiter and Latona are the equivalents of the Greek Zeus and Leto.

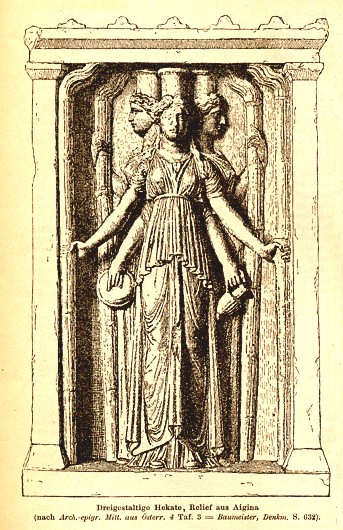

Catullus' poem describes the multiple roles ascribed to her: Goddess of the woodlands; Luna, personification of the moon; identification with Juno Lucina, goddess of women in childbirth (by connection with the monthly cycle of the moon); Trivia, goddess of the crossroads (literally, where "three roads,"tres viae," meet), hence identification with Hecate, goddess of the Underworld, to whom forks in the road were particularly sacred. Diana is also invoked as a goddess of agricultural fertility, who brings good crops to the farmer.

Perhaps to be sung by a chorus of girls and boys

The metre in which the poem is written consists of short, staccato lines. (Technically, each stanza is composed of three Glyconics (-u|-uu|-u|-) followed by one Pherecratic (-u|-uu|-|-).) E.T. Merrill suggests that the song was to be performed by a chorus of girls and boys, with some verses chanted by just the girls (those pertaining to Diana's birth and childbirth), others just by the boys, and the first and last verses sung by both. Merrill suggests that the performance may have been at the annual festival of Diana at her temple on the Aventine, held at the time of the full moon in the month of August.

Below, in Latin and English, is Catullus' prayer to Diana.

Catullus Carmen 34Dianae sumus in fidepuellae et pueri integri: Dianam pueri integri puellaeque canamus. O Latonia, maximi magna progenies Iovis, quam mater prope Deliam deposivit olivam, montium domina ut fores silvarumque virentium saltuumque reconditorum amniumque sonantum: tu Lucina dolentibus Iuno dicta puerperis, tu potens Trivia et notho es dicta lumine Luna. tu cursu, dea, menstruo metiens iter annuum, rustica agricolae bonis tecta frugibus exples. Sis quocumque tibi placet sancta nomine, Romulique, antique ut solita es, bona sospites ope gentem. |

Goddess of many names, be generous to the people of RomulusWe are under the protection of Diana,chaste girls and boys. Chaste boys and girls let us sing to Diana. Daughter of Latona, great offspring of greatest Jove, whose mother bore you near the Delian olive tree, so that you might be mistress of the mountains and the verdant woods and the hidden woodlands and the sonorous rivers. You are called Lucina Juno by women suffering in childbirth; you are called powerful Trivia and Luna with your borrowed light. You, goddess, in your monthly course measuring earth's journey, fill the rustic home of the farmer with good crops. May you be holy by whatever name pleases you, and, as you are accustomed of old, preserve the race of Romulus with good wealth. |

Three-headed Hekate, relief from Aigina. Illustration from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890).

Quotation for March, 2019

Hoopoe

Arcturus and migratory birds herald the coming of spring (Hesiod, Works and Days 564-570 |

Above: "The Rape of Philomela by Tereus." Engraved by Johann Wilhelm Baur for a 1703 edition of Ovid's Metamorphoses Book 6, plate 59. Top: Eurasian hoopoe, eating an insect, photo by Artemy Voikhansky, May 9, 2014. Tereus, according to one version of the myth, was transformed into a hoopoe.

Spring is finally here

Spring is finally here in the Northern hemisphere, birds are twittering, and they and the squirrels are chasing each other around getting ready to mate and have offspring. The migratory birds are back, some preparing to stay here, others simply stopping on their way to somewhere farther north.

For our Quotation of the Month, we turn to Hesiod's Works and Days for his advice to the farmer (or backyard farmer) on spring pruning, in verses 564-570.

Hesiod bids the farmer prune his vines

Hesiod spends only a few lines on Spring, sandwiched in between frigid Winter and enervating Summer. Winter is the time when Boreas blows his chill wind, and both animals and humans seek shelter. The oxen, not needed until spring, are put on half rations (but not the human help; they need their food). In Summer, when "women are most wanton and men are feeblest," you should find a nice shady rock behind which to enjoy your lunch and wine. In Spring, however, the most important task is to prune your grape vines, ready for the growing season.

Arcturus rises and the swallows return

The coming of spring is heralded by two events, the rising of the star Arcturus, a "red giant" that is the brightest star in the constellation Bootes ("the herdsman"), and the return of the swallows.

Hesiod calls the swallow "daughter of Pandion," a reference to a myth that exists in many different versions. In the most common version, told by Ovid, Pandion, king of Athens, had two daughters, Procne and Philomela. Procne was married to Tereus, king of Thrace, but he was attracted to her sister Philomela, raped her, and cut out here tongue so that she could not tell anyone. But she wove a tapestry that told the story, and the two sisters took revenge by killing Procne's son Itys, cooking him, and serving him up to his father Tereus. (Other versions of the story reverse the roles, with Philomela married to Tereus and Procne the victim.) The gods eventually turned them all into birds, the usual telling making Procne into a swallow, Philomela into a nightingale, and Tereus into a hoopoe, a bird with an extravagant and exhibistionistic crown of golden feathers (Aristophanes' version; others make him into a hawk). Sophocles told the story in his (lost) play Tereus. The nightingale is said to mourn by singing a sad song, a concept that implies that her tongue was not cut out after all, but in real life, only the male nightingale sings, to attract a mate. The story of infanticide has obvious parallels to the story of Medea, and there could be some influence of one story on the other.

Hesiod does not tell us which version of the story he knew, but he speaks only of the swallow, whether that was Procne or Philomela. The swallow, like the nightingale, is a migratory bird. Northern European species winter in Africa, those in North America winter in South America. Their return in spring is a welcome harbinger of good weather to come. Their song is anything but mournful, being a cheerful "twit twit twit twit twit TWEET!"

Below, in Greek and English, is Hesiod's characterization of the arrival of spring.

Hesiod Works and Days vv. 564-570

|

When Arcturus rises and the swallows sing, prune your vinesWhen after the solstice Zeus has completed sixtywintry days, then the star Arcturus, leaving the sacred stream of Ocean, first rises, shining brightly, at the beginning of twilight. After him, the swallow, daughter of Pandion, with early morning cries, appears to men, when spring is just beginning. Before she arrives, prune the grape vines; that way is best. |

Swallows' nests photographed at the railroad station, Fort Smith, Arkansas, June 12, 2014. The beak of one bird can barely be seen peeking out from the third nest from the right. Photo by C.A. Sowa.

Quotation for February, 2019

Full moon, total lunar eclipse

A Supermoon for the Snow Moon of February: Homeric Hymn XXXII to Selene |

Above: Bust of Selene, Goddess of the Moon, from a Roman sarcophagus, early 3rd century A.D. Photograph by Marie-Lan Nguyen (2006). Top left: Full moon as seen from Madison, Alabama, October 22, 2010, photographed by Gregory H. Revera. Top right: Total lunar eclipse, October 7, 2014, as seen from Lomita, California, photographed by Alfredo Garcia, Jr.

A Supermoon, when the full moon is closest to the Earth, blazes like a searchlight in the sky

When the full moon (or the new moon) coincides with the moon's perigee, the closest that it comes to earth in its elliptical orbit, it is known as a "supermoon." It appears larger and brighter than usual, and when it is at its highest point, it blazes like a searchlight in the night sky. In 2019, we have a series of three full moon supermoons in a row, January 21, February 19, and March 21. (A curmudgeon will tell you that the applellation "supermoon" isn't a scientific term, but let's use it anyway.) The January supermoon, spectacularly, was also a total eclipse, turning into a huge, blood-red ball at its height.

The Snow Moon of February

The February supermoon coincided with the Snow Moon. It is called that because February is the month of the greatest snow fall. Some Native American tribes called it the Hunger Moon, because weather made hunting difficult. February does not always even have a full moon, but this year's blinding Supermoon was the brightest of all this season's supermoons. We still have March to look forward to.

The Homeric Hymn XXXII to Selene

Our Quotation of the Month is the Homeric Hymn XXXII to Selene, Goddess of the Moon. The Homeric Hymns, approximately from the time of Homer (ca. 750 B.C.) are all anonymous, but our unknown bard may have had a supermoon in mind when he described the brilliant radiance of the moon as Selene, in her chariot drawn by a team of "arch-necked shining" steeds, courses across the sky.

Selene (Roman Luna), sister of Helios, the Sun, was often identified with Artemis, just as Helios was often identified with Apollo. Helios and Selene, however, are not so much mythological figures as personifications of Sun and Moon. Yet there are stories about Selene, one of which is included in the Hymn. As with many other maidens, willing and unwilling, Zeus had sex with Selene and she had a child by him, the beautiful Pandia ("All goddess").

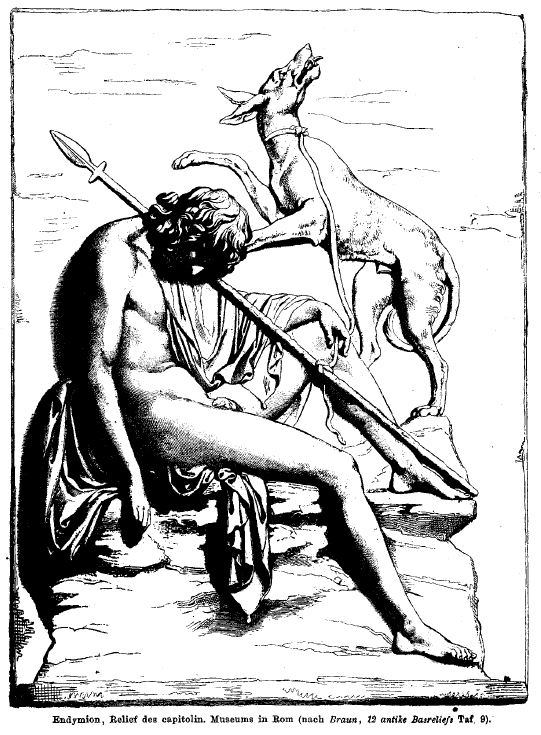

Selene and Endymion

However, Selene was not always the victim; sometimes she is depicted as the aggressor. There are many versions of the story, but the basic idea is that she fell in love with a beautiful young man named Endymion. In some versions he is a shepherd, in others a hunter, a king, or even an astronomer who liked to study the moon. At the request of Selene, Zeus made him immortal and forever young by putting him in perpetual sleep (in some versions, Endymion himself made the request). Selene visits him every night, and she is supposed to have had fifty daughters by him. (The mechanics of this arrangement are unclear!)

Below, in Greek and English, is the bard's celebration of the radiant lady of the night. Note that in the first line of the poem, the poet uses another word for "moon," Mênê. As we see in other Homeric Hymns, the final lines lead directly to another song; this practice leads scholars to believe that these short poems were intended as preludes to longer songs.

Homeric Hymn XXXII to Selene

|