The Eureka Machine for Composing Hexameter Latin Verses

(1845)

THE EUREKA

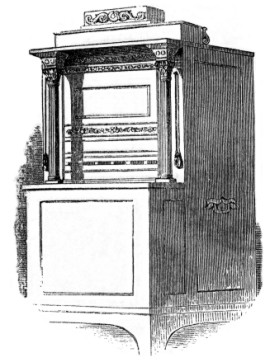

Illustration from The Illustrated London News, July 1845

(Click here to see how the Eureka machine looks today.)

A Victorian special-purpose computer

When we think of computers, in our foreshortened view of history, we see them as a recent phenomenon We forget that the abacus and sundial are ancient, and must be reminded that the computer had many predecessors, in the form of astronomical and mathematical calculators (including those designed by the philosophers Pascal and Leibniz). In particular, we view as modern the application of computers to non-scientific or creative problems such as robotics, artificial intelligence, composing children's stories, or creating movie panoramas of armies and dinosaurs by machine. But these more humanistic applications of machines also had their precursors. Among these was the Eureka machine of 1845, an early multimedia machine.

In 1845, John Clark built the Eureka Machine for Composing Hexameter Latin Verses, which he exhibited it at Egyptian Hall in Picadilly. Words were pre-encoded on turning cylinders, whose projecting pins would cause letters to drop, forming Latin verses. The cylinders were turned random amounts, so that a different verse was formed each time, but each verse had the same grammatical shape: adjective, substantive, adverb, verb, substantive, adjective. An example of a verse produced by the Eureka (in which we must forgive an improper short first "a" in mala!) runs:

BARBARA FROENA DOMI PROMITTUNT FOEDERA MALA"Barbarian bridles at home promise evil covenants"

The machine also played music and created an abstract visual display.

The original article describing the debut of the Eureka, which was published in The Illustrated London News on July 19, 1845, appears below. The illustration accompanying the article is reproduced at the head of this page.

Clark belonged to the family that founded C & J Clark Shoes, and the actual historic machine, restored in 1951, now resides in the Shoe Museum, Street, Somerset, England (see "Further Information about the Eureka Machine" below).

There is more about the Eureka machine and many other historic machines in the chapters of the self-study CD The Loom of Minerva: An Introduction to Computer Projects for the Literary Scholar, of which the first chapter "A Guide to the Labyrinth" can be read on this Web site. Included on the CD is a suite of programs for the study of literary texts. One of them, COMPOSE, uses pre-encoded phrases (stored as tables in a database) to construct sentences having the form: introductory phrase, subject phrase, verb phrase, object phrase. It is thus similar in concept to Clark's Eureka, but where the Eureka used cylinders that spun a random amount, when set in motion by clockwork, COMPOSE uses a random number generator (the RND function in Visual Basic). You can get more information about The Loom of Minerva by e-mailing me at casowa@aol.com.

The EurekaSuch is the name of a Machine for Composing Hexameter Latin Verses, which is now exhibited at the Egyptian Hall, in Piccadilly. It was designed and constructed at Bridgewater, in Somersetshire; was begun in 1830, and completed in 1843; and it has lately been brought to the metropolis, to contribute to the "sights of the season." The exterior of the machine resembles, in form, a small bureau book-case; in the frontispiece of which, through an aperture, the verses appear in succession as they are composed. The machine is described by the Inventor as neither more nor lees than a practical illustration of the law of evolution. The process of composition is not by words already formed, but from separate letters. This fact is obvious; although some spectators may, probably, have mistaken the effect for the cause — the result for the principle, which is that of Kaleidoscopic evolution; and, as an illustration of this principle it is that the machine is interesting — a principle affording a far greater scope of extension than has hitherto been attempted. The machine contains letters in alphabetical arrangement. Out of these, through the medium of numbers, rendered tangible by being expressed by Indentures on wheel-work, the instrument selects such as are requisite to form the verse conceived; the components of words suited to form hexameters being alone previously calculated, the harmonious combination of which will be found to practically interminable. The rate of composition is about one verse per minute, or sixty in an hour. "Each verse remains stationary and visible a sufficient time for a copy of it to be taken; after which the machine gives an audible notice that the Line is about to be decomposed. Each Letter of the verse is then slowly and separately removed into its former alphabetical arrangement; on which the machine stops, until another verse be required. Or, by withdrawing the stop, it may be made to go on continually, producing in one day and night, or twenty-four hours, about 1440 Latin verses; or, in a whole week (Sundays included), about 10,000. "During the composition of each line, a cylinder in the interior of the machine performs the National Anthem. As soon as the verse is complete, a short pause of silence ensues. "On the announcement that the line is about to be broken up, the cylinder performs the air of "Fly not yet," until every letter is returned into its proper place in the alphabet. There is on the frontispiece of the machine, above the line of verse, a tablet, bearing the following Inscription: — " 'Full many a gem, of purest ray serene, The primum mobile, or first moving power of the machine, is a leaden weight of about twenty pounds, with an auxiliary weight of ten pounds, applied to another part of the movement: these are occasionally wound up, and the velocity is regulated in the usual manner, by a worm and fly. "The entire machine contains about 86 wheels, giving motion to cylinders, cranks, spirals, pullies, levers, springs, ratchets, quadrants, tractors, snails, worm and fly, heart-wheels, eccentric-wheels, and star-wheels — all of which are in essential and effective motion, with various degrees of velocity, each performing its part in proper time and place. And in the front of the interior is a large Kaleidoscope, which regularly constructs a splendid geometric figure. This action is performed at the commencement of the operation, and at the precise time when the line of verse is conceived, previous to its mechanical composition." From The Illustrated London News, July 19, 1845. |

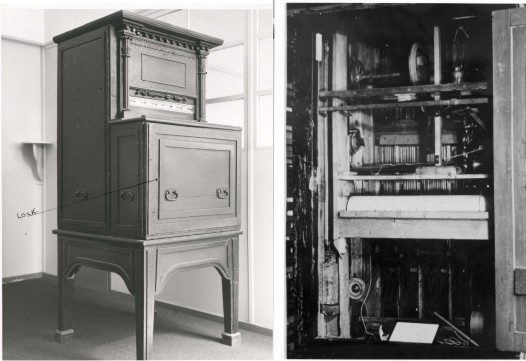

This is how the Eureka looks today, outside and inside. (Photos courtesy of The Shoe Museum, Street, Somerset.) |

Further information about the Eureka machine

For further reading about the Eureka, see:

Clark, R., "Barbara Froena Domi Promittunt Foedera Mala," in Somerset Anthology (P. Lovell, ed.), pp. 96-102, York: Sessions, 1975. This particular article (with the title taken from a verse produced by the machine) was written in 1951, at the time of the machine's restoration.

Foster, C., "Notes on the Mechanical Construction of the Machine for Composing Hexameter Latin Verse," March 8, 1951.

Randell, Brian (ed.), The Origins of Digital Computers, Selected Papers, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 3rd ed. 1982. These are in many cases the actual papers in which historic machines and significant ideas were first introduced. The extensive bibliography includes references for the Eureka machine.

As of 2005, the Eureka machine is at the (C & J Clark) Shoe Museum, whose address is: The Shoe Museum, Clarks Village, Street, BA 16 0YA, Somerset, England; telephone 01458 842 169; e-mail Janet.Targett@clarks.com. In answer to an e-mail to the museum, I am told that unfortunately the machine is currently stored where it cannot be viewed by the public.

I am indebted to Prof. Brian Randell of the University of Newcastle

Upon Tyne and the Shoe Museum in Street, Somerset, England for

information about how the Eureka machine works and about its current

location.

On this Web page, you are visitor number:

Last Modified: