These are quotations for the year 2018. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2018, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2018 |

Below are quotations for the year 2018. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2018

Click on a link to read each quotation

2018

- December, 2018: For the Winter Solstice: An Early American Poem in Latin Addressed to the Sun.

- November, 2018: For the U.S. Elections: Democrats Take the House of Representatives as Women Take the Lead: Dux Femina Facti in Aeneid Book 1.

- October, 2018: For Halloween: Palinurus, Murdered, Unburied, and Prevented from Entering the Underworld, Appeals to Aeneas (Aeneid Book 6).

- September, 2018: After Labor Day, it's Time to Go Back to Work! The Prologue to Hesiod's Works and Days.

- August, 2018: Global Warming: A Description of Hephaestus' Furnace in Iliad Book 18.

- July, 2018: A Horrifying Parallel with the Present Immigrant Crisis: Captive Andromache Laments the Killing of her Son, Astyanax (Euripides Trojan Women).

- June, 2018: For the Kentucky Derby and the Triple Crown, the Birth of Pegasus (Hesiod, Theogony 270-294).

- May, 2018: Where did the Month of May Get Its Name? (Just ask the Muses): Ovid's Fasti Book 5.

- April, 2018: For Earth Day, the Prolog to Vergil's Georgics.

- March, 2018: For the Beginning of Spring, a Poem From the Appendix Ausoniana.

- February, 2018: For the Lunar Year of the Dog: Odysseus' Dog Argus Recognizes his Disguised Master (Odyssey Book 17).

- January, 2018: For Rev. Martin Luther King's Birthday: Petronius Arbiter on Making Your Own Dreams.

Quotation for December, 2018

For the Winter Solstice: An Early American Poem in Latin Addressed to the Sun |

Above: Helios in his chariot, driving his horses — they were named Pyrois, Eous, Aethon, and Phlegon — on a marble sculpture from the temple of Athena, Ilion, 3rd or 4th century B.C. Discovered by Heinrich Schliemann in 1874, this piece is now in the Pergamon-Museum in Berlin. (Illustration from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890). Top: The Sun of May (Sol de Mayo), taken from the flag of Uruguay. The Sun of May is said to represent Inti, the sun god of the Inca religion. The phrase "of May" refers to the May Revolution of 1810 which marked the beginning of independence from Spain. Just as the new government was proclaimed, the sun is said to have broken through the clouds, a good omen.

We are happy to see the Sun return

At this time of year, we celebrate the solstice, the solstitium, when the Sun seems to stand still and change direction. In the Northern Hemisphere, the days become longer, and the Sun begins its seemingly miraculous return. Yes, the coldest and snowiest months still lie ahead, but the return of sunlight is still encouraging. This is the time of winter festivals, whether we celebrate Christmas, as the birthday of the infant Jesus, or Hanukkah, with its miraculously long-burning lights, or Kwanzaa, commemorating the seven principles of African philosophy, or dance around the steadfast fir tree, which remains green all winter. Or perhaps we just bang pots and pans to bring back the sun.

A Latin invocation to the Sun, written in 1774

For December's Quotation of the Month, we bring you a Latin poem written in the Colony of Virginia in 1774, celebrating the Sun as the bringer of all good things on earth. It is taken from Early American Latin Verse, edited by Leo M. Kaiser (Bolchazy-Carducci, 1984). The author is not known, but it was part of a yearly submission to the Governor of Virginia as a condition of the charter of the College of William and Mary. Several of these poems, on various topics, are included in this anthology. Here is the description that is provided:

According to its charter of 1693, the College of William and Mary was granted by its namesake British majesties 20,000 acres of land, providing that each year, forever, on the fifth of November, the president and professors of the College deposit at the house of the Governor or Vice-Governor of Virginia duo exemplaria carminum lingua latina conscriptorum ["Two examples of poems written in the Latin language"]. William Byrd in his Diary of 5 November 1711 mentions his witnessing that day the presentation of two Latin poems to the Governor. Only a half-dozen or so poems, from the period 1771-1774 have come to light.

Our poem is addressed "To his Excellency, the Right Honourable John, Earl of Dunmore, His Majesty's Lieutenant Governor General, Commander in Chief of the Colony and Dominion of Virginia, and Vice-Admiral of the Same." We are told in a note that "In 1774 Governor Dunmore led an army to the Ohio River to destroy an Indian coalition formed to check the rapid expansion of Virginia." Hence the reference in the final lines of the poem to the poet's desire to serve as official bard for the "warrior" (bellator) Dunmore.

Below, in Latin and English, is our colonial hymn to the Sun. The first part praises the Sun as the bringer of light and crop fertility. In the second part, the Sun takes on the role of Apollo, as inspirer of poets. The Fiery Planet (Pyrois) is Mars.

To His Excellency, etc., Nonis Novembris MDCCLXXIV Solis InvocatioSol, qui perpetua mundum vertigine lustrasalme parens rerum, caeli decus et stellarum princeps, aeterni fons luminis, undique cernens omnia, puniceo dum Persida linquis ab ortu, et pergens tandem occiduis obsconderis undis, atque eadem rursus repetis vestigia semper, per te cuncta patent, noctis quibus umbra colorem abstulerat, tenebris tua non patientibus ora. Mundi oculus, qui transverso dum limite curris per duodena means animantum idola, quaternis dispensas annum spatiis, et tempora mutas et cum temporibus quicquid generatur in orbe. O sanctum jubar, o divum pelcherrime, salve! Te colimus, tibi sincero de pectore laudes fundimus: at tu hodie laeto nos respice vultu et laetum concede diem redeasque benignus. Nubila diffugiant, aer sit ubique serenus, adventuque tuo ponti vada salsa quiescant, et sit iter tutum cupidis per caerula nautis. Non segeti, non arboribus, non vitibus imber insanusve obsit turbo lapidosave grando, sed blandas Pyrois afflet mortalibus auras, accipiantque tuo reditu, Deus, omnia pacem. Salve, praesidium et sacris tutela poetis! Tu vatum mentes divino numine reples, ipsorum moves ad dulcia carmina linguas, tu dignos lauroque facis famaque perenni. Salve igitur dexterque mihi sis quaeso petenti, et faveas coeptis et nostros dirige cursus. Me non immerito tum Dux Dunmorus amabit et tollet secum bellator in aethera vatem: sic aquila scindas subvectus regule nubes. |

Sun, bringer of light, inspirer of poetsSun, who go round the world in a perpetual whirl,nourishing procreator of things, ornament of heaven and chief among stars, origin of eternal light, perceiving everything everywhere, as you depart Persia from your purple rising, proceeding at last to hide yourself in the setting waves, and back again always repeat the same footsteps, for you all things lie exposed, from which the shade of night has taken away the color, in shadows that cannot endure your face. Eye of the world, who racing across the crosswise path, and passing through twelve images of living beings, distribute the year in four areas, and change the seasons and with the seasons whatever is produced upon the globe, O sacred radiance, o most beautiful of gods, hail! We worship you, from sincere hearts we pour forth praise. But may you look upon us with joyful countenance and grant us a joyful day and be beneficent on your return. Let the clouds disperse, let the air be clear, at your approach let the salty depths be at rest, and let the way across the blue sea be safe for eager sailors. For the crops, the trees, the vines, let no rainstorm be an obstruction, or raging whirlwind or stone-like hail, but let the Fiery Planet blow caressing breezes upon mortals, and let all things receive peace at your return, o God. Hail, protector and safeguard of sacred poets! You fill the minds of bards with divine power, you move their utterances toward sweet songs, you make them worthy of the laurel and everlasting fame. Hail, therefore, and be favorable to me, I beg you, and be favorable to my undertakings and guide my course. Then I will be deserving that Governor Dunmorus will love me and as a warrior he will take me as a bard into the upper air. Thus as prince may you, conveyed by an eagle, part the clouds. |

Sundial at Sailors' Snug Harbor Cultural Center, Staten Island, New York. Photo by C.A. Sowa.

Quotation for November, 2018

For the U.S. Elections: Democrats Take the House of Representatives as Women Take the Lead: Dux Femina Facti in Aeneid Book 1 |

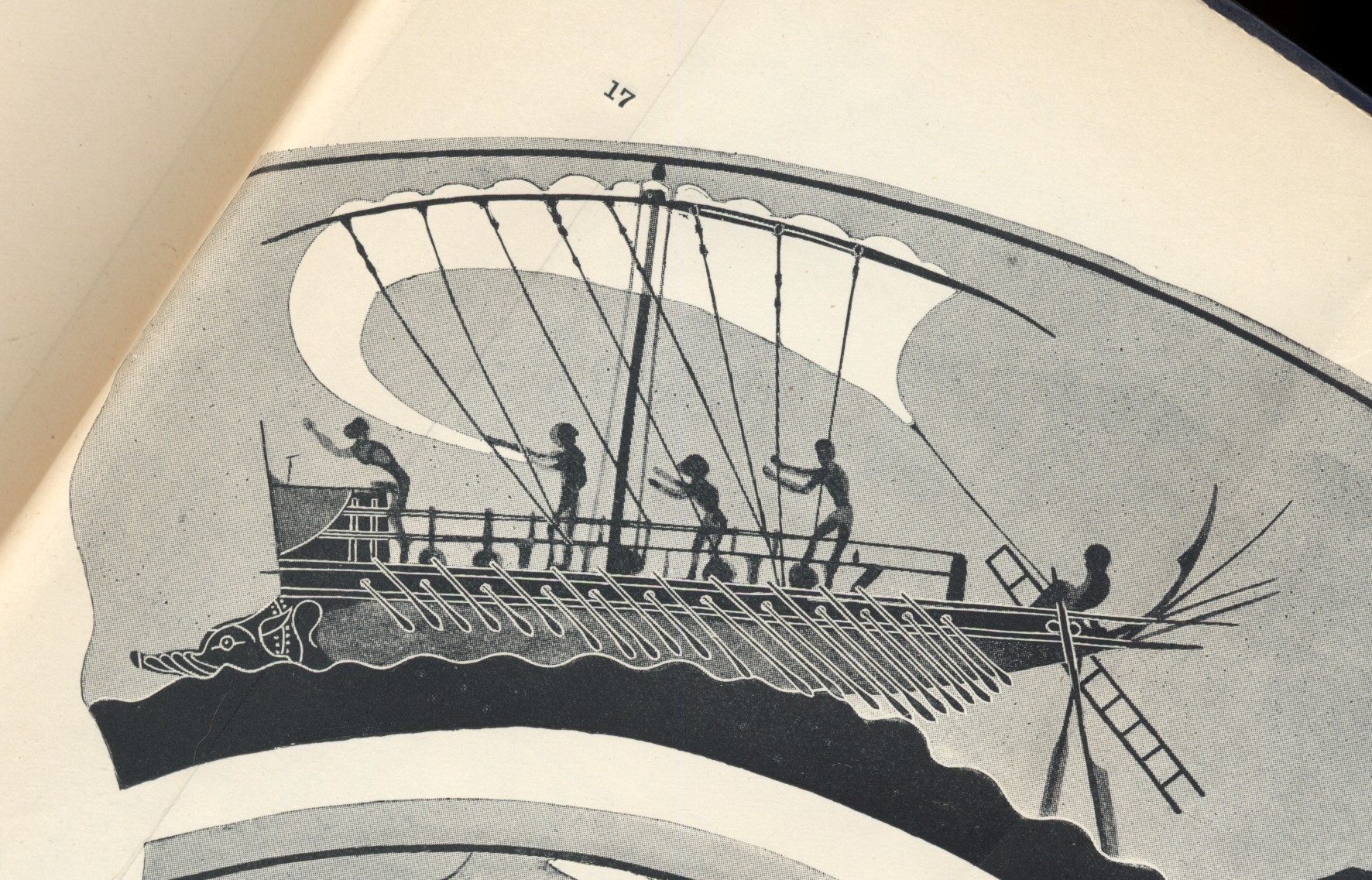

Above: Ruins of ancient Carthage in Tunisia. Photo by Patrick Verdier, Free On Line Photos, from Wikimedia. Top: Ancient ship, from Cecil Torr, Ancient Ships, 1895.

Record numbers of women enter the U.S. Congress

In the elections of November 6, a record number of new women members were elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Many, though not all, were Democrats, and the Democrats took over the House. Of the new Congresswomen, two were Muslim and two were Native American, reflecting the nation's diversity. The Senate remained in Republican hands, and Republican Donald Trump is still President. Yet the balance of power has become more even.

Nancy Pelosi of California, former and probably future Speaker of the House, did not mention women in her victory speech the night of the election. The next day, however, interviewed on ABC, she crowed "Women led the way to victory, with at least 30 new women coming to the Congress. Is that not exciting?" As a matter of fact, the number was 36, as of November 16. In an interview with CNN's Dana Bash, posted on November 13, for her series "Badass Women of Washington," Pelosi said, "I take some, for lack of a better term, badass glee in just saying, Women, you know how to get it done; you know your power," and then, "I want women to see that you do not get pushed around." Pelosi, the daughter and sister of two mayors of Baltimore, told how she herself did not immediately go into politics, but got married and had "five children in six years." Only when her youngest daughter was a senior in high school did she run for a seat in Congress. Today, as she reminded us, women of child-bearing age are increasingly entering politics

Dux femina facti: Dido leads her people to found a new city

Did Nancy d'Alesandro Pelosi, the daughter of Italian immigrants, know that she was channeling one of the greatest of Italian epics, the Aeneid of Roman Vergil? Her triumphant words "Women led the way" immediately call to mind "Dux femina facti" "A woman was leader of the deed," said of Dido in Aeneid Book One v. 364.

In the first book of the Aeneid, Aeneas, seeking shelter from storms sent by Neptune, seeks a safe harbor in Libya. There he is taken in by Queen Dido, leading a group of Phoenicians from Tyre who are building the new city of Carthage (in present day Tunisia). Dido is fleeing from the dictatorship of her brother Pygmalion, who had murdered her husband Sychaeus and made himself sole tyrant of the city of Tyre, which was supposed to be jointly governed by brother and sister. The ghost of Sychaeus appears in a dream to Dido, and tells her where Pygmalion has hidden a fortune in gold and silver. She appropriates the hoard, commandeers a ship, and sets forth with a group of followers to start a new city. She was, as Vergil says, "the leader of the deed."

We do not know if Dido was a real person or not, but she may well be based on a real Middle Eastern leader. The Phoenicians did build a series of settlements along the north coast of Africa, controlling trade routes to the rich mines of Spain. The most successful of these was Carthage, which in historic times was Rome's great rival, destroyed by Rome in the Punic Wars.

Vergil's women characters

Vergil has sometimes been praised for his introduction of strong women characters, but they seem regularly to meet a bad end. Dido, after hearing Aeneas' tales of his adventures in Books II-III, falls in love with Aeneas and wants him to stay and help her build her city. But his mission is to found his own new city in Italy and walks (or rather sails) out on her, and she commits suicide. In Book 11 of the Aeneid we meet Camilla, bold huntress and leader of the Volsci, who are allied with Aeneas' rival Turnus. She fights bravely, but is slain in battle (Aeneid 11.759-835). With Dido, history has been conflated with a romantic story of thwarted love.

Below, in Latin and English, is the passage in Book I where Dido, warned by Sychaeus' ghost, leads her people to Libya (Aeneid I.353-368). As in the Loeb edition, I have appended v. 426, which seems out of place in its original position between vv. 425 and 427, but the line may not belong in the poem at all. Vergil includes the story that Dido purchased the land, supposedly the extent that could be covered with a bull's hide, but she cheated by cutting the hide into strips, which were used to encompass a much larger piece of property. The phrase "called Byrsa after the fact" incorrectly derives the name of the location from the Greek byrsa "animal hide," but it actually comes from the Phoenician word bosra meaning "citadel."

Vergil Aeneid 1.353-368 (plus v. 426). . .Ipsa sed in somnis inhumati venit imago coniugis; ora modis attollens pallida miris, crudelis aras traiectaque pectora ferro nudavit, caecumque domus scelus omne retexit. Tum celerare fugam patriaque excedere suadet, auxiliumque viae veteres tellure recludit thesauros, ignotum argenti pondus et auri. His commota fugam Dido sociosque parabat. conveniunt quibus aut odium crudele tyranni aut metus acer erat; navis, quae forte paratae, corripiunt, onerantque auro; portantur avari Pygmalionis opes pelago; dux femina facti. Devenere locos, ubi nunc ingentia cernes moenia surgentemque novae Karthaginis arcem, mercatique solum, facti de nomine Byrsam, taurino quantum possent circumdare tergo. Iura magistratusque legunt sanctumque senatum. . . . |

Fleeing her brother, Dido leads her people from Tyre to LibyaBut in her sleep there came the very imageof her unburied husband; wondrously raising his pale face, he laid bare the cruel altars and the breast pierced with iron, and uncovered all the hidden evils of the house. Then he counseled her to take hasty flight and leave her native land, and as an aid to her journey he revealed ancient treasures, a mass of silver and gold known to none. Moved by these words Dido prepared her flight and her companions. There came together those who had unmerciful hatred for the tyrant or who felt keen fear; they seized ships, which by chance were ready, and loaded them with gold. The wealth of grasping Pygmalion is borne across the sea; a woman is leader of the deed. They came to a place where now you will see walls and the rising citadel of New Carthage, and bought land — called Byrsa after the fact — as much as they could encompass with a bull's hide. Now they are choosing laws and magistrates and an august senate. . . . . . . |

The triumphal arch at Tyre in Lebanon, as reconstructed. Photo by David Bjorgen, from Wikimedia.

Quotation for October, 2018

For Halloween: Palinurus, Murdered, Unburied, and Prevented from Entering the Underworld, Appeals to Aeneas (Aeneid Book 6) |

Above:Capo Palinuro, Campania, Italy. On this rocky headland Aeneas' unlucky helmsman Palinurus is said to have lost his life. (Image by Foto, from Wikimedia.) Top: A coquettish skeleton for the Día de los Muertos (from the collection of C.A. Sowa).

Two ghosts from the Aeneid: Anchises and Palinurus

On October 31, we celebrate Halloween (All Hallows Eve), which may have its origins in an old Celtic harvest festival. In the Catholic calendar, November 1 is All Saints Day, and November 2 is All Souls Day. The latter is celebrated in Mexico and in Mexican communities as the Día de los Muertos (the Day of the Dead, more correctly, Día de Muertos). On that day, people go to the cemeteries to visit the souls of dead family members. For our Quotation of the Month for October (and the beginning of November), we bring you a visit by the Trojan hero Aeneas with two ghosts, that of Aeneas' father Anchises and that of the gallant steersman Palinurus, who was washed overboard just as Aeneas' fleet was reaching the long-anticipated shores of Italy. The quotation is from Book 6 of Vergil's Aeneid.

Leaving Dido, Aeneas pauses in Sicily, where games are held to honor Anchises

In Book 4 of the Aeneid. Vergil tells the story of Aeneas' famous interlude with Queen Dido of Carthage, a city in North Africa that in historic times was a major competitor of Rome (remember Hannibal crossing the Alps with elephants). Dido, crazy with passion, thinks that Aeneas, having escaped from Troy, will marry her and help her build her city. But Mercury, sent by Jupiter, reminds Aeneas of his mission to found a new city in Italy. He leaves, and Dido commits suicide, climbing to the top of a sacrificial pyre, where she stabs herself and burns to ashes. In the opera Dido and Aeneas (ca. 1683) by the baroque composer Henry Purcell, Dido sings "When I am laid in earth, remember me, but ah! forget my fate." In Vergil, Dido is not so charitable. She ends her life with a long rant against Aeneas, and her last words are a curse against him and all his descendants.

In Book 5, Aeneas sets sail for Italy, as Dido's funeral pyre burns in the distance. A storm comes up, and the steersman Palinurus advises that the fleet take shelter in Sicily, where they had gone before visiting Carthage. There Aeneas' aged father Anchises, was buried, and Aeneas' friend and fellow Trojan, Acestes. was living, Aeneas holds games to celebrate the anniversary of Anchises' death. But while the men celebrate the contests, the Trojan women, incited by the goddess Juno, set fire to the ships. They have had enough of wandering, and want to settle down. (Those pesky women, again, like Dido, always wanting to distract Aeneas from his divine mission!) Jupiter sends rain, which puts out the fire, and the ships are rebuilt.

A visit from the spirit of Anchises

At night, Aeneas, full of doubts, is visited by the spirit of his father Anchises, sent by Jupiter. Anchises urges him on his mission, and tells him to seek the aid of the Cumaean Sibyl and journey to the Underworld. Anchises, now dwelling in Elysium, will prophesy to him the future of the Roman race. Then the ghost disappears, "like smoke in the breeze" (ceu fumus in auras) even as Aeneas tries to embrace him (Book 5.740).

But Jupiter's aid comes at a price. In exchange for safe passage to Italy, one life will be lost (unum pro multis dabitur caput, "One life will be given for many," Book 5.815). The god of Sleep is sent to incapacitate Palinurus. Disguised as a sailor named Phorbas, Sleep encourages Palinurus to take a nap, while he takes over his shift. But Palinurus, distrusting the sea, clings doggedly to the tiller At last Sleep drugs Palinurus with waters from the rivers Lethe and Styx, and throws him overboard, taking part of the rudder with him. Aeneas, sensing that the ship is drifting toward the cliffs, takes over steering the vessel, and holds Palinurus reponsible for being "too trusting of the calm sky and sea" (Book 5.870).

Aeneas, aided by the Cumaean Sibyl, visits the Underworld and meets the spirit of Palinurus

Finally arrived in Italy, Aeneas visits the Cumaean Sibyl, who takes him to the entrance to the Underworld. There he sees a great throng of people trying to get in. Many are denied entrance because, though dead, they have never had a proper burial. Among these is Palinurus. Pathetically, he tells Aeneas how he was washed overboard, apparently oblivious to Jupiter's role in the matter. Ever the faithful sailor, he was less worried for himself than for the fate of Aeneas' ship. He drifted for three days, and at last was able to swim to shore, where he grasped at the rocky mountainside. Just as he pulled himself up, a band of brigands killed him, thinking that he was carrying valuables. Then they tossed him back onto the beach. He implores Aeneas to throw a handful of earth on him, recognized as a symbolic burial, or to take him with him so that he can find rest in a peaceful spot. Aeneas berates the oracle of Apollo for tricking him into believing that Palinurus would safely reach Italian land. Of course the oracle had not, technically, lied to him. Palinurus had, in fact, reached land. It was the brigands who killed him.

The Sibyl sternly tells Palinurus that his wish cannot be granted. But she assuages his grief by telling him that the local inhabitants will build him a tomb, and will bring offerings to it. And forever more, the rocky point in Campania will be called by his name. And there it is, to this day: Capo Palinuro. And that is how we know the story is true.

Below, in Latin and English, is Palinurus' story of how he was washed overboard, still clutching the ship's tiller, thus (although he did not know it) fulfilling the will of the gods.

Vergil Aeneid 6.337-383Ecce gubernator sese Palinurus agebat,qui Libyco nuper cursu, dum sidera servat, exciderat puppi mediis effusus in undis. hunc ubi vix multa maestum cognovit in umbra, sic prior adloquitur: "quis te, Palinure, deorum eripuit nobis medioque sub aequore mersit? dic age. namque mihi, fallax haud ante repertus, hoc uno responso animum delusit Apollo, qui fore te ponto incolumem finisque canebat venturum Ausonios. en haec promissa fides est?" ille autem: "neque te Phoebi cortina fefellit, dux Anchisiade, nec me deus aequore mersit. namque gubernaclum multa vi forte revulsum, cui datus haerebam custos cursusque regebam, praecipitans traxi mecum. maria aspera iuro non ullum pro me tantum cepisse timorem, quam tua ne spoliata armis, excussa magistro, deficeret tantis navis surgentibus undis. tris Notus hibernas immensa per aequora noctes vexit me violentus aqua; vix lumine quarto prospexi Italiam summa sublimis ab unda. paulatim adnabam terrae; iam tuta tenebam, ni gens crudelis madida cum veste gravatum prensantemque uncis manibus capita aspera montis ferro invasisset praedamque ignara putasset. nunc me fluctus habet versantque in litore venti. quod te per caeli iucundum lumen et auras, per genitorem oro, per spes surgentis Iuli, eripe me his, invicte, malis: aut tu mihi terram inice, namque potes, portusque require Velinos; aut tu, si qua via est, si quam tibi diva creatrix ostendit (neque enim, credo, sine numine divum flumina tanta paras Stygiamque innare paludem), da dextram misero et tecum me tolle per undas, sedibus ut saltem placidis in morte quiescam." talia fatus erat coepit cum talia vates: "unde haec, o Palinure, tibi tam dira cupido? tu Stygias inhumatus aquas amnemque severum Eumenidum aspicies, ripamve iniussus adibis? desine fata deum flecti sperare precando, sed cape dicta memor, duri solacia casus. nam tua finitimi, longe lateque per urbes prodigiis acti caelestibus, ossa piabunt et statuent tumulum et tumulo sollemnia mittent, aeternumque locus Palinuri nomen habebit." his dictis curae emotae pulsusque parumper corde dolor tristi; gaudet cognomine terra. |

Despite my efforts, I was dashed overboard, the tiller still in my handAnd behold! the helmsman Palinurus was walking around,who recently, on the voyage from Libya, while he kept watch on the stars, fell from the stern, swallowed by the waves. When Aeneas, with difficulty recognized, in the deep shadows, the sorrowful figure, he first spoke thus: "Which of the gods, Palinurus, snatched you from us and submerged you beneath the waters? Come tell me, for Apollo, never before found false, with this one answer deceived me, who prophesied that you would escape unharmed from the sea and would reach the Ausonian lands. Is this a trustworthy promise?" He then answered: "Neither did the tripod of Phoebus deceive you my leader, son of Anchises, nor did a god submerge me in the sea. For the rudder being by chance violently torn from me, as I clung to it watchfully steering our course, I dragged it with me as I fell headlong. By the harsh seas I swear I felt not so much fear for myself as that your ship, stripped of its gear and wrested from its master, might fail in such great surging waves. For three wintry nights upon the measureless seas the South Wind carried me violently upon the water. Scarcely at the fourth dawn I looked upon Italy as I was carried high above a wave. Little by little I swam toward land; already I was grasping at — and would have achieved — safety if a cruel tribe, even as I, weighed down with wet clothes, clawed with bent fingers at the rugged sides of the cliff, had not assailed me with swords, ignorantly thinking that I was a rich prize. Now the waves hold me, and the winds toss me on the beach. And so, by the pleasing light and breezes of Heaven, by your father I beseech you, by the hope of your growing son Iulus, snatch me from these evils, you who are invincible. Either cast some earth on me, for you can do that, seeking again the port of Velia or else, if there is a way, if your goddess mother shows you, (for, I believe, it is not without divine favor that you prepare to sail upon these great streams and upon the Stygian marsh) give your right hand to one so miserable and take me with you over the waves, so that at least in death I may lie quietly in a peaceful place." Thus he spoke, and the seeress began with these words: "O Palinurus, whence does such an awful desire come to you? Are you, unburied, to look upon the Stygian waters and the stern river of the Furies, and will you, unbidden, approach its shore? Cease to hope that the gods' decrees can be turned aside by prayer, but listen to and remember my words, a solace for your hard lot. for the neighboring people, far and wide among their cities, driven by celestial portents, will appease your bones, and will build a tomb, and to that tomb send solemn offerings, and the place will have the eternal name of Palinurus." At these words his cares are removed, and for a little while grief is driven from his sad heart, and the land rejoices in the name. . . . |

Aeneas carrying his father, the aged Anchises, as they flee from Troy after the defeat by the Greeks. Black-figured oinochoe, ca. 520-510 B.C., Louvre F118, Paravey Collection, 1879. (Photo by Bibi Saint_Pol,from Wikipedia.)

Quotation for September, 2018

Ploughing

After Labor Day, it's Time to Go Back to Work! The Prologue to Hesiod's Works and Days |

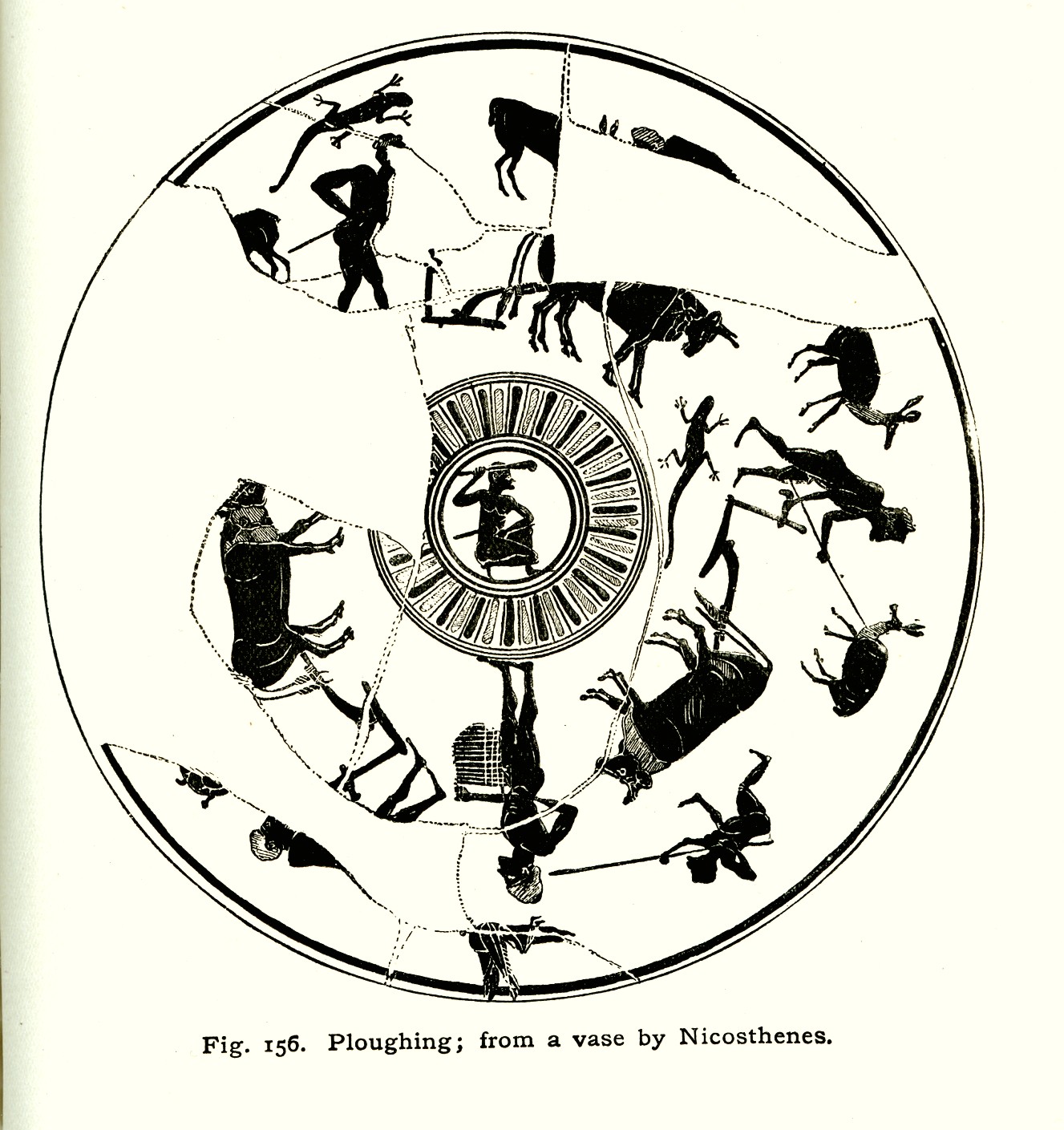

Above: Olives being harvested by beating the trees with sticks. Attic black figure amphora attributed to the Antimenes Painter, 520 B.C. British Museum No. 1837,0609.42. Top: Ploughing, from Leonard Whibley, A Companion to Greek Studies, 1916, p. 637.

After Labor Day we get back to work or school

September begins in the U.S. with Labor Day, and ends with the population going back to work after (what we hope was) a long summer holiday. For students, this means the start of the fall semester.

Retail stores are beginning to set things up for Halloween and Christmas (they already ordered their merchandise last spring). Road crews are laying in piles of salt to melt the ice, and making sure their snowplows are in good repair. Homeowners are thinking about new snowshovels, and buying lots of flashlights in case the electricity goes out. And the last tomatoes are being harvested from our backyards.

Our Quotation of the Month is from Hesiod's Works and Days, in which farmer/poet Hesiod preaches the need for such forethoughtedness and preparation. Our pictorial illustrations show a variety of ancient occupations.

Hesiod lectures his brother Perses on responsible behavior

The Works and Days (Erga kai Hemerai) is best known as a didactic poem on farming, an Old Farmer's Almanac of the seasons of the year, with advice on activities appropriate to each season. But almost the first half of the poem (verses 1-382 out of a poem of 828 verses) is taken up by a long rant addressed to his ne'er-do-well brother Perses, who would rather waste time and money (some of which should be Hesiod's) than work for a living. This rant is illustrated by the mythological tales of Pandora and the Five Ages.

We cannot know for sure whether the events Hesiod describes actually happened to him or are fictionalized or semi-fictionalized and embellished for the sake of telling a good story. But considering the intensity of feeling that Hesiod puts into its telling, it seems likely that the story is mostly true.

Hesiod and Perses' father had apparently intended to leave his estate to his two sons equally, but Perses bribed the crooked ("bribe-eating," dorophagous) lords of the district to give Perses the larger share. These crooked men, Hesiod says ironically, "love to judge this kind of case" (v. 39). Perses prefers hanging around the market place (agora), watching disputes and law cases to minding the farm. He may also have spent his money on women, as Hesiod warns against "butt-displaying" women (pygestolos, "dressing up her butt") who are "only after your barn" (v. 374). Hesiod's extreme misogyny, which shows up in many parts of the Works and Days (particularly in his telling of the Pandora story), may have had its roots at least partly in his experience with his brother. Not all women were evil in Hesiod's universe, of course. In a later passage, Hesiod assumes that Perses will be married and have children, whom he sees as suffering along with Perses as he begs from the neighbors because of his own improvidence (vv. 387-402). He also advises Perses to get a slave woman to keep the house and help with the plowing (vv. 405-407).

There is nothing wrong with wanting wealth, but, says Hesiod, "if your heart within you desires wealth, do this: to work work upon work" (ergon ep' ergo ergazesthai).

Stories of Pandora, the Five Ages, Might makes right

Hesiod told the story of the First Woman twice, once in the Theogony and once in the Works and Days, but only in the latter did he give her the name Pandora ("All-endowed"). It is one of three mythological stories that Hesiod introduces during his long address to his brother, as an explanation of why men have to work for a living. Zeus hid fire from mortals because Prometheus had tricked him. We know from the Theogony that this involved keeping the best part of a sacrifice for mortals, leaving the skin and bones for the gods. Prometheus (himself a god, being of the older race of Titans) stole fire back, hiding it in a hollow fennel stalk. In revenge, Zeus had Hephaestus make Pandora, whom all the gods endowed with beauty, cleverness, and deceitful thoughts. She opened the famous jar, letting out all the evils, but keeping Hope trapped inside.

The second myth is that of the Five Ages: the Golden Age; the Silver Age; the Bronze Age; the Age of Heroes (the age of Oedipus' Thebes and the Trojan War, which was, of course, the actual Bronze Age); and the Iron Age.

The third myth is the tale of the nightingale and the hawk, who tells the nightingale, which it holds in its talons, that it is the hawk's choice whether to eat the smaller bird or let it go. Might makes right. After this myth, the advice to Perses on justice, keeping your friends, and getting wealth the right way continues. Work work upon work.

Below, in Greek and English, is an extract from Hesiod's rant addressed to his brother. The line in v. 41 about the value of "mallow and asphodel" refers to two humble vegetables eaten by poor people.

Hesiod Works and Days vv. 27-52

|

Stop wasting your time and and the money you stole from meO Perses, put this advice away in your heart:Do not let Strife, who delights in evil, draw your mind from work, as you are gawking at and listening to the disputes of the public square. He has little care for disputes and assemblies who does not have abundant victuals stored up at the proper season, that which the earth bears, Demeter's grain. When you have a sufficiency of that, you can increase your disputes and battles over other people's property. However, you will get no second chance to do that. Let us settle our own dispute with true judgment, which is of Zeus and is best. For we already divided our inheritance, but you seized the greater share and carried it off, greatly gladdening our bribe-devouring lords, who love to judge such a case. Fools! They do not know how much more half is than the whole, nor what advantage there is in mallow and asphodel. For the gods keep hidden the means of life from mortals. Otherwise you could work enough in one day to have a supply for a year, even without working. You could quickly hang your steering oar over the smoke, and the fields worked by oxen and hard-working mules would run to ruin. But Zeus hid it, angry in his heart, because crafty Prometheus deceived him. For that reason he planned miserable death against mankind. He hid the fire. But the noble son of Iapetus stole it again for mankind, from Zeus the counsellor, in a hollow fennel stalk, hiding his deed from Zeus who delights in thunder. . . . [There follows the story of Pandora and the stories of the Five Ages and of the Hawk and the Nightingale.] |

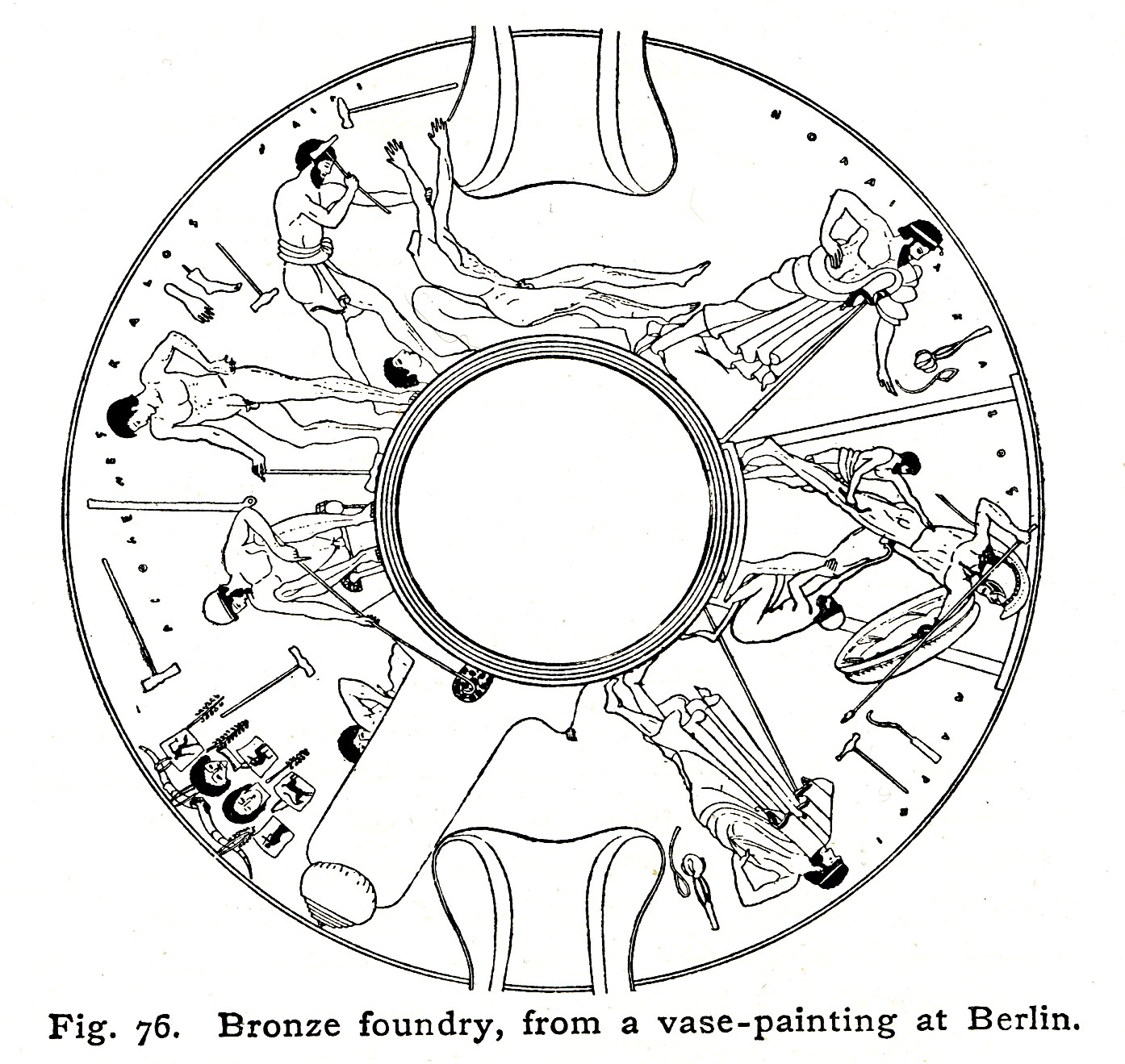

Left: Bronze foundry, from a vase painting in Berlin. From Leonard Whibley, A Companion to Greek Studies, 1916, p. 356. Right: Painting from the fuller's shop, Pompeii. From Oskar Seyffert, A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899, p. 243.

Quotation for August, 2018

Anvil, hammer, & tongs

Global Warming: A Description of Hephaestus' Furnace in Iliad Book 18 |

Hephaestus at his forge, aided by Cyclopes. (Image from Roscher, Ausfürliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.)

It feels like walking into a furnace

The effects of global warming are everywhere. In the U.S. Pacific Northwest, the woodlands are on fire. In Sweden, forest fires burn near the Arctic Circle. In the northeastern United States, we have had heat wave after heat wave.

When you walk outside, it feels like walking into a furnace.

The goddess Thetis visits Hephaestus' forge

For this month's Quotation of the Month, we bring you what is perhaps the most famous ancient furnace, the forge of the craftsman god Hephaestus, as described in Book 18 of the Iliad.

As the Iliad begins in Book I, the Greek commander Agamemnon is forced to give back the maiden Chryseis whom he has taken as spoils of war from a Trojan-allied town. She is the daughter of a priest of Apollo who calls down a plague on the Greeks if he does not return her. Agamemnon will only give her back if he can have another girl, Briseis, who was the spoils given to the Greek hero Achilles. Achilles, in anger at losing Briseis, sulks in his hut at the Greek camp and refuses to fight. Finally he sends his best friend Patroclus out in his own armor to fight. Patroclus, wearing Achilles' armor, is killed by the Trojan hero Hector. Achilles now reenters the fight, vowing not to bury Patroclus until he has slain Hector.

Thetis asks Hephaestus for a favor: the Shield of Achilles

Thetis, Achilles' sea-nymph mother, goes to Hephaestus to ask him to make her son a new suit of armor, since his was lost with Patroclus' death. Hephaestus owes Thetis a really big favor, as she once saved his life. The goddess Hera gave birth to Hephaestus without any father, in revenge for her husband Zeus giving birth to Athena. But, in the version of the story followed by Homer, Hera threw him from Heaven because he was lame from birth. (In another version, it was Zeus who threw him down, causing his lameness.) The goddess Thetis and a fellow sea-nymph Eurynome took him in and raised him. He lived in the cave of Thetis and Eurynome surrounded by the Ocean for nine years, during which he amused himself by practicing his metal-working skills, making jewelry and ornaments for the goddesses. Hephaestus is happy to see Thetis again, and he has his wife, in this version the goddess Charis ("Grace"), keep her entertained while he puts away his tools and gets cleaned up from his work.

For Achilles, Hephaestus makes a new suit of armor. The pièce de resistance is the mighty shield, with scenes of many kinds depicted on it, cities, crowds, festivals, warfare, vineyards. herds of cattle, sacrificial events, rivers, wild beasts, and every kind of human endeavor, a pictorial encyclopedia of Bronze Age life.

Ancient robotics, self-driving tripods, and artificial intelligence

When Thetis visits Hephaestus, he is sweating and running around between a phalanx of fires and bellows, forging a set of twenty self-driving tripods, that could wheel themselves automatically up to Olympus and back, when needed by the gods. In an example of ancient robotics, he has also made himself a set of handmaidens made of gold, who help him to get around when he has trouble walking because of his lameness. This is also a case of extremely ancient artificial intelligence, as the robot maidens are given intellect (nous, "mind") as well as the ability to speak.

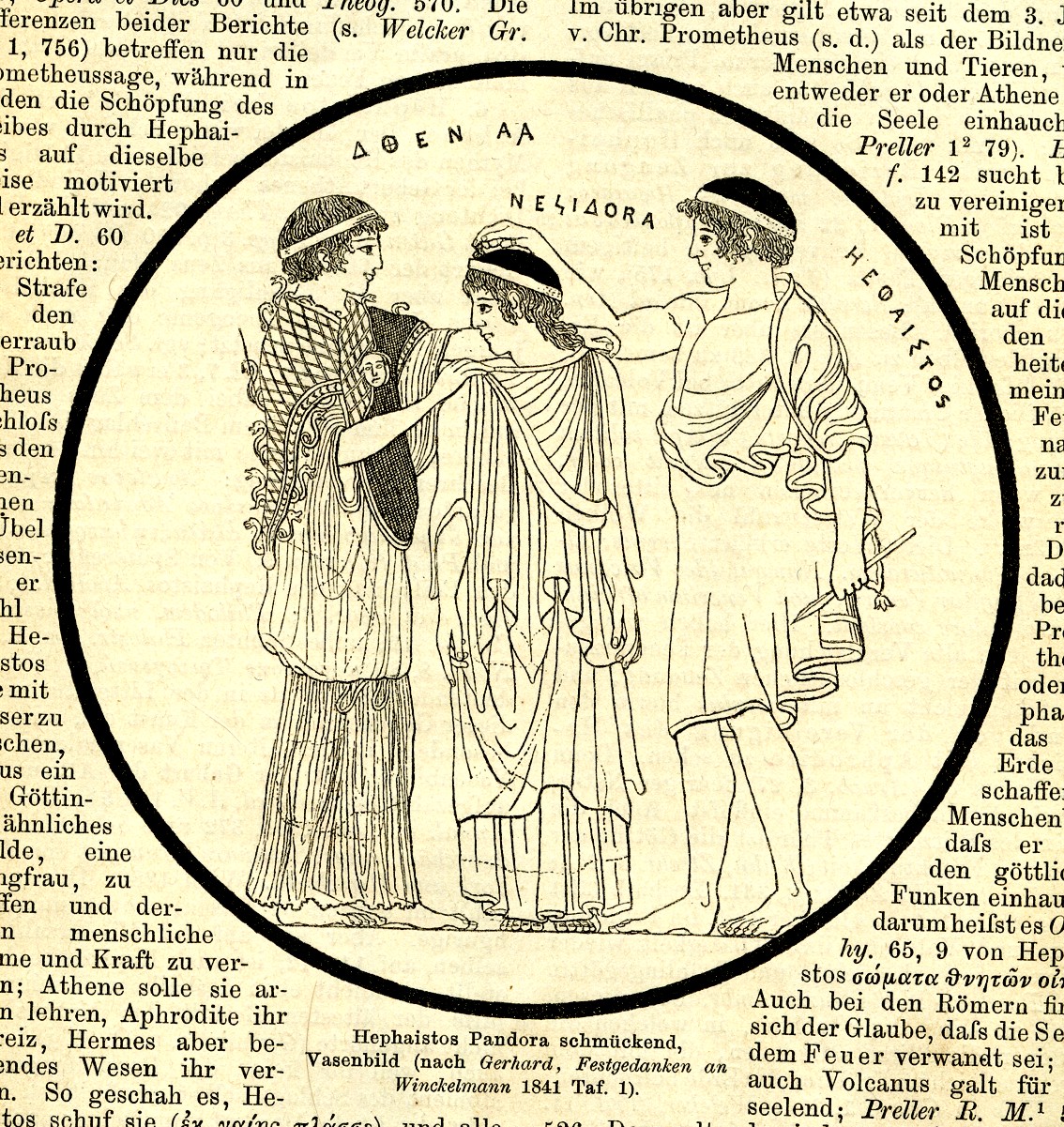

Hephaestus and Pandora, with a pictorial golden crown

In ancient epic, Hephaestus was credited with many other lifelike inventions. One of these was Pandora, the First Woman. Hesiod told this story in two different versions, in his Theogony (vv. 570-612) and Works and Days (vv.60-89). In both, she is fashioned from clay, and with misogynistic fervor, is described as bringing nothing but trouble to men. Only in the Works and Days she is given the name Pandora, "All Gifts," and in her he puts the "voice and strength of a human being." In both poems the woman is given a crown of flowers, but in the Theogony she is also given a golden crown that resembles the Shield of Achilles in its elaborate decorations, depicting creatures of land and sea. The illustration at the bottom of this article shows Hephaestus and Athena outfitting the manufactured woman, but here she is given the name Anesidora, "She Who Sends Up Gifts."

Below, in Greek and English, are extracts from the passage in Book 18 of the Iliad (vv. 369-387, 410-427) describing Hephaestus at his forge, visited by Thetis.

Homer Iliad

|

Hephaestus sweats at his furnaceSilver-sandalled Thetis arrived at the house of Hephaestus,which was imperishable, sparkling like a star, preeminent among the immortals, made of bronze, which the crooked-footed god had built himself. She found him sweating, turning hither and thither about his bellows, working in haste. For he was making tripods, twenty in all, to stand around the wall of his well-built hall, and he placed golden wheels around the bottom of each so that they could automatically enter the gathering of the gods and then return home again, a wonder to behold. They were now complete, except that the cleverly made ears were not yet attached. He was making these ready, and was hammering out the connecting pieces. As he was laboring at these things, with experienced mind, meanwhile silver-sandalled goddess Thetis came near to him. Then beautiful Charis of the shining veil saw her, Charis, whom the famous crook-footed god had married. And she took her by the hand and spoke and addressed her: "Why, Thetis of the long robe, do you come to our house, honored and dear to us? For you have not come often before. But follow me further, that I may offer you hospitality." . . . [Charis calls to Hephaestus to come, and he recounts how Thetis saved his life when his mother threw him down from Heaven. He asks Charis to entertain Thetis while he puts away his tools.]

. . . He spoke, and rose from his anvil, huge and monstrous, |

Hephaestus and Athena outfit Pandora, just created by Hephaestus. (Image from Roscher, Ausfürliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.) In this vase painting, the manufactured girl is named "Anesidora," "She Who Sends Up Gifts," instead of "Pandora," "All Gifts."

Quotation for July, 2018

Hecuba

A Horrifying Parallel with the Present Immigrant Crisis: Captive Andromache Laments the Killing of her Son, Astyanax (Euripides Trojan Women). |

Astyanax, sitting on the lap of his mother, Andromache, touches the helmet of his father Hector. Apulian red-figure column crater, ca. 370-360 B.C. Image from Wikipedia, photo by Jastrow, from the Iliade exhibition at the Colosseum, September 2006–February 2007. Top: Hecuba, Queen of Troy, from the Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum, 1553, published by Guillaume Rouille (1518?-1589).

America betrays its own ideals

America is a proud country of high ideals and democratic traditions, but many times actions have been taken that betray those ideals with a horrifying meanness and cruelty. We are witnessing one of those actions today, in the treatment of immigrants, especially those from Mexico and Central America, where children have been ripped from their parents' arms and detained without hope, in some cases, of ever being reunited. Children are shipped to distant locations, as far away as New York, while the parents are held in holding pens on the Mexican border, not knowing where their childen are. In some cases, it is difficult to determine which children should be matched with which adults, as no system of identification was in place. A simple method of putting identification bracelets on the children, like the ones used in hospitals, could have helped, but nothing was done. Some mothers have already been deported; their children may never see them again.

Euripides' Trojan Women

Our Quotation of the Month describes an ancient situation where a child is torn shamefully from the hands of a defeated mother. In this case, the child is to be killed. It comes from Euripides' Trojan Women, a play about the suffering of the women and children of Troy, following the glorious defeat of Troy by the Greeks, which was described in the Iliad. (Another "take" on the fate of the Trojans would later form the premise of Vergil's Aeneid.) The play was produced in 415 B.C., during the Peloponnesian War, when Athens, another state with high ideals, had committed its own atrocities against the citizens of Melos. The play is thought to be a comentary on that episode.

The fate of the Trojan survivors was not glorious. The men have been killed, and the women are to be given to the Greek soldiers as sex slaves. The Greeks decide that Astyanax (the name means "Lord of the City"), young son of the Trojan hero Hector, who was killed by Achilles, shall not be allowed to live, because he might grow up to avenge his father. In our quotation, Hector's widow, Andromache, has just learned that Astyanax is to be hurled off the ramparts of Troy to his death. As she hugs the weeping child for the last time, he is led away.

Andromache ends her lament with curses against Helen, who caused the Trojan War in the first place. She refers to Helen as "daughter of Tyndareus," the king to whom her mother Leda was married, although her real father was Zeus. It was her leaving the Greek king Menelaus for the Trojan prince Paris that caused the conflict. In later passages of the play, Menelaus himself wants to kill Helen, but he relents, and we see in the Odyssey that Menelaus and Helen are back together, peacefully ruling over the prosperous kingdom of Sparta.

Andromache goes into exile

Andromache at least wants to give Astyanax a suitable funeral, burying him on his father's shield. But like the deported immigrant women of today, who will never see their chidren again, Andromache, too, will have left already, to be a concubine to Achilles' son Neoptolemus. The ship has sailed. It falls to Hecuba, widow of King Priam, to bury her grandchild.

Below, in Greek and English, are the lines from Euripides in which Andromache bids farewell to Astyanax.

Euripides, Trojan Women vv. 740-779

|

Andromache laments as Astyanax is torn from herO dearest one, o child exceedingly prized,you die at the hands of enemies, leaving your wretched mother. It is your father's nobility that kills you, born to be salvation for others; but your father's bravery comes too late for you. O ill-starred marriage-bed and nuptials, with which I once came to Hector's house, not to give birth to a sacrificial victim for the Greeks, but to one destined to be a king of fertile Asia. O child, you are crying! Do you perceive your misfortune? Why do you seize me with your hands and cling to my skirts, like a baby bird hiding beneath my wings? Hector will not come, seizing his famous spear, rising from the ground to bring you salvation, nor will your father's kindred, nor the Phrygians' strength. With a grievous leap from above you will fall without pity upon your neck and burst your windpipe. O young burden of my arms, dearest to your mother, O sweet odor of your skin! In vain, then, did this breast nourish you in your swaddling clothes, and vainly I toiled and wore myself out with cares. Now — and never again — embrace your mother, fall down before her who bore you, wind your arms around my back and join your lips to mine. O Greeks, who invent barbarous evils, why do you kill this child, who is guilty of nothng? O offspring of Tyndareus, you are not sprung from Zeus, but I declare that you were born of many fathers, first from the Avenging Spirit, then from Envy, Murder, and Death, and as many evils as earth nourishes. I never say that you were born of Zeus, a death-spirit to both barbarians and Greeks. Go to perdition! With your beautiful eyes you have shamefully destroyed the famous plains of Phrygia. Lead him away, carry him away, throw him over, if throwing seems good, feast on his flesh. It is by the gods that we are destroyed, and we cannot ward off death from my son. Hide my miserable frame and cast me into the ship. For I am going to a beautiful wedding, having lost my child. |

.jpg)

This is what's left of Troy today. The remaining walls of Troy VII, Hisarlik, Turkey, the level of ruins considered to be the city of the Trojan War. Image from Wikipedia, by CherryX per Wikimedia Commons, uploaded September 27, 2012.

Quotation for June, 2018

Medusa

For the Kentucky Derby and the Triple Crown, the Birth of Pegasus (Hesiod, Theogony 270-294) |

Pegasus, the flying horse, symbol of strength and speed, flies proudly today on a gas station sign (collection of C.A. Sowa).

Champion "Justify" wins the Triple Crown

Galloping to victory at New York's Belmont Stakes, undefeated Justify led wire to wire, always in the lead, finishing first by a length and three quarters. He thus achieved horse racing's Triple Crown, having won this season's Kentucky Derby, Preakness, and the Belmont. Trained by Bob Baffert, Justify was the 13th horse to capture the Triple Crown, giving Baffert his second Triple Crown winner. Another Baffert-trained horse, American Pharoah, won all three races in 2015.

Mike Smith, Justify's jockey, also set a record by being the oldest jockey, at 52, to ride a Triple Corwn winner.

Pegasus born from the severed head of Medusa

This month, in honor of Justify, and the sport of horse racing, we bring you Hesiod's telling, in the Theogony, of the birth of Pegasus, legendary flying horse, from the blood of the Gorgon Medusa.

Hesiod tells the story in its simplest form, as part of a long catalog of characters, with their genealogies and a few details of their eventful lives. These appear to be well-known tales, and it seems that Hesiod expects his audience to be familiar with them. We are dependent on later sources, such as Pindar and Aeschylus, Apollodorus and Hyginus, or the Roman poetry of Ovid, for full tellings of the stories, of which there are multiple versions. We cannot know for certain which versions Hesiod knew, although there are hints in artistic representations from archaic and later periods.

The Gorgons and the Graiae

Medusa was one of three Gorgon sisters, who were also sisters of the Graiae, ("Old Women"), who were born with gray hair. Hesiod names only two Graiae, but other versions name three, and tell us that they shared one eye and one tooth between them. The Gorgons, too, in archaic art, were always hideous, scary monsters, with snakes for hair or around their waists (see the picture at the top of this article). In Ovid's Metamorphoses and in later art, Medusa was once beautiful, punished by Athena who turned her hair to snakes. Original hair or no, she was so scary that to see her face turned men to stone. In the standard story, Perseus, sent by King Polydectes on a suicide mission to bring back the head of Medusa, stole the eye and tooth from the Graiae to make them tell him where the Gorgon sisters were, then looking at Medusa in the mirror-like surface of Athena's shield to avoid being turned to stone, he decapitated her. Other variants provide Perseus with a cap of invisibility and winged shoes.

From the blood of Medusa, there sprang up the winged horse Pegasus and the giant Chrysaor. Hesiod derives the name Pegasus from the springs (pegae) of Ocean, but Pegasus was also famous for creating springs wherever his hoofs struck the ground. Mounting to Olympus, he also brings thunder and lightning to Zeus when he needs them. His brother Chrysaor, on the other hand, became the father of the monster Geryon, whose cattle Heracles stole as one of his Labors. To the student of mythology, the birth of Pegasus from the head of Medusa seems analogous to the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus after he swallowed her mother Metis ("Forethought"), as well as the birth of Aphrodite from the severed genitals of Uranus ("Heaven") after Cronus cut him apart from Earth.

Bellerophon and Pegasus

Pegasus also became part of the myth of Bellerophon. Sent to kill the Chimera, Bellerophon is usually depicted as capturing Pegasus as the horse is drinking from the spring at Pirene, in Corinth. (Hesiod follows another version in his Catalogs of Women, saying that his father gave the horse to Bellerophon.) The Chimera, in most representations, had the body of a goat, the head of a lion, and the tail of a serpent. (The word chimaira means "she-goat.")

Pegasus in modern times

The winged horse remains a powerful symbol, a beloved figure of strength and speed. The flying horse, red in color, was first used as a company logo by Vacuum Oil in South Africa in 1911. Previously, Vacuum Oil had used a red gargoyle as a symbol for its petroleum-based lubricating oils. The high-flying horse remained through many corporate mergers, until the company became Mobil Oil, and now today's Exxon Mobil. A giant rotating neon-lighted red horse on the company's former headquarters in Dallas has now been restored.

So the next time you pass a Mobil gas station, or pause to refuel your own swift steed, look around, and you will see Pegasus, the immortal flying horse.

Below, in Greek and English, are the lines from Hesiod in which he traces the genealogy of Pegasus and his brother of the golden sword, Chrysaor.

Hesiod, Theogony vv. 270-294

|

Pegasus and Chrysaor born from Medusa's severed headCeto bore to Phorcys the Graiae of the beautiful cheeks,gray-haired from birth, whom the immortal gods and men who walk on earth call "Graiae," Pemphredo the well-robed and Enyo of the saffron robe. And she bore the Gorgons, who live beyond glorious Ocean on the borderlands toward Night, where are the clear-voiced Hesperides, Sthenno and Euryale and Medusa, who suffered a mournful fate, for she was mortal, the other two immortal and ageless. With Medusa the Dark-haired One lay in love, in a soft meadow among spring flowers. After Perseus cut off her head, there leaped forth great Chyrsaor and the horse Pegasus, the latter so named because he was born by Ocean's springs, the former because he held in his hands a golden sword. The one flew away, leaving the earth, mother of sheep and goats, and came to the immortal gods. He lives in the house of Zeus, bringing to wise Zeus the thunder and lightning. But Chrysaor begot three-headed Geryon, joined in love with Calirhoe, daughter of glorious Ocean. Geryon was slain by mighty Heracles beside his oxen of the rolling gait, in sea-girt Erytheia on that day when Heracles drove the broad-browed oxen to holy Tiryns, crossing the strait of Ocean, killing Orthus and the herdsman Eurytion in the misty farmyard beyond glorious Ocean. |

Bellerophon and Pegasus, who drinks from the spring. (Image from Roscher, Ausfürliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1884.)

Quotation for May, 2018

Where did the Month of May Get Its Name? (Just ask the Muses): Ovid's Fasti Book 5 |

A Muse in Grant Park, Chicago. Officially known as the Spirit of Music, she is part of a memorial to Theodore Thomas, founder of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, sculpted by Albin Polasek (1923). (Photo by C.A. Sowa, November 20, 2017.)

Why is the month of May called that?

Where did the name of the month of May come from? The answer seems like a no-brainer. Obviously, May was named for Maia, one of the Pleiades, mother of Hermes (Mercury) by Zeus (Jupiter). The Romans identified Maia with Terra (Earth) or with the Bona Dea (the Good Goddess). And the name of the month of June obviously is derived from the name of the goddess Juno. Or is any of this true?

Ovid, in Book 5 of his Fasti, or Festival Calendar, is just as curious as we are. So he did the logical thing, and consulted the Muses. Ever whimsical and inventive, Ovid considered that as a bard, he could be on familiar terms with any god he wanted to talk to. In January, for example, he encounters the double-faced god Janus, with whom, once he gets over his initial fright at the god's strange appearance, he has a long conversation. So these Muses are not the mystical beings encountered by Hesiod in his Theogony, but straightforward and familiar partners in conversation.

The Muses disagree

But the goddesses disagree! Polyhymnia begins, and the others "remain silent, but take mental notes." Polyhymnia provides a history of the universe, which begins with Chaos, as in Hesiod, but then diverges wildly. Ovid's Chaos is as much metaphorical as literal. After the Earth sank of its own weight, taking the waters with it, and Heaven rose of its own lightness, none of the other heavenly bodies and various divinities knew what place to occupy, and even "plebeian" gods were sitting on the heavenly throne. Finally, Honor and Reverence gave birth to Majesty (Maiestas), who sorted things out, and now sits beside Jupiter. From her name comes the name of "May."

The Muses Clio and Thalia agree with Polyhymnia, but Urania offers another explanation. She contends that in olden days age was held in reverence, and so the name of "May" honors the elders (maiores) and the name of June honors youth (juniores). Then Calliope chimes in, claiming that "May" indeed honors Maia, mother of Mercury, connecting that god with the story of Evander of Arcadia, who legend says founded a city on the future site of Rome, bringing his native gods with him.

Ovid wisely decides that he wants the favor of all the Muses, and he will not choose between them.

And what about June?

In Book 6 of the Fasti, Ovid is puzzled again. Apparently the question of the name of "June" is still not settled. Three more goddeses appear to the poet. The goddess Juno, queen of the gods, appears first, scaring the poet at first. She is angry. She is both sister and wife of Jupiter, and she knows not which makes her more proud. If, she says, May can be named for Maia, a mere paelex (mistress), surely she herself, as wife, can have a month named after her. But then Hebe, wife of Hercules and goddess of youth (called Iuventas in Latin), claims the month for herself. Finally, the goddess Concord appears, and suggests that the name of June comes from legendary Roman history, and is named for the junction of two kingdoms ruled by Tatius and Quirinus. The implication is that peace can be achieved.

Once again, Ovid refuses to render judgment, remembering that in the Judgment of Paris, a decision in a beauty contest between three goddesses led to the Trojan War.

Below, in Latin and English, are the opening lines of the fifth book of Ovid's Fasti. Aganippe and Hippocrene ("the Horse's Spring") are two springs on Mount Helicon, associated with the Muses. Here, the two are identified as one. Hippocrene is supposed to have risen from a blow by the hoof of the winged horse Pegasus, ridden by Bellerophon in his defeat of the Chimera. One story has it that Pegasus sprang from the blood of the monster Medusa when she was beheaded by Perseus.

Ovid, Fasti Book 5 vv. 1-10Quaeritis, unde putem Maio data nomina mensi?Non satis est liquido cognita causa mihi. Ut stat et incertus qua sit sibi nescit eundum, cum videt ex omni parte viator iter: sic, quia posse datur diversas reddere causas, qua ferar, ignoro, copiaque ipsa nocet. Dicite, quae fontes Aganippidos Hippocrenes grata Medusaei signa tenetis equi. Dissensere deae. Quarum Polyhymnia coepit prima; silent aliae dictaque mente notant. . . |

Just ask the Muses — but they disagree!You ask, whence I think the name was given to the month of May?The reason is not clearly known to me. Just as the traveler stands, uncertain which way he should go, when he sees roads in all directions, so, because it is possible to assign different causes, I do not know whither I should turn, and the very abundance is an impediment. Tell me, you who inhabit the springs of Aganippean Hippocrene, welcome footprints of Medusa's horse. The goddesses disagreed! Of them, Polyhymnia began first; the others were silent but took mental notes . . . |

The Muse Erato. (Image from Roscher, Ausfürliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1884.)

Quotation for April, 2018

For Earth Day, the Prolog to Vergil's Georgics |

Orpheus in a bucolic landscape, by the German artist Hans Thoma (1839-1924), whose painting of the goddess Flora appeared in the March 2018 web page. Thoma painted scenes of rural life, in his native Bavaria and in Italy, as well as allegorical and mythological subjects. This is another mythic scene, painted in 1898.Illustration from Thoma, des Meisters Gemälde in 874 Abbildungen, 1909.)

The Earth's bounty

In April we celebrate Earth Day, when we reconnect with Mother Earth and renew our commitment to protect and preserve this wonderful planet. As spring and summer begin, we renew our appreciation of Earth's gifts to us — the soil, rocks, and sand, the trees and flowers, the rivers, mountains, deserts, and glaciers, the clouds, rain, wind, and snow. We relearn, if we have forgotten, our relationship to animals, insects, and fish — all the creatures that creep, that crawl, that fly and run and swim, that purr and bark and chirp and caw.

The ancient Greeks and Romans, like all who grow up in rural environments, lived close to nature. Their depictions of trees and animals, their moods, emotions, and behavior, were not just abstract or poetical, they were part of the life they lived. Their divinities were close to Nature, too. The god Pan, half-goat, is understandable when we realize that his favored country of Arcadia is a rocky hardscrabble land where the only cattle that can be raised are goats and sheep.

Vergil's Georgics: sympathy with Nature

Our Quotation of the Month consists of the opening verses of Vergil's Georgics (ca. 29 B.C.), a hexameter poem on agriculture in four books. In Book I, he treats the raising of crops, in Book II the cultivation of grape vines, in Book III the rearing of cattle, and in Book IV the care of bees. Practical information is adorned with mythic tales, including the story of Orpheus and Euridice in Book Four. His models and influences were many. An obvious Greek antecedent is Hesiod's Works and Days, the Boeotian Old Farmer's Almanac. He also drew on Aratus' Phaenomena, on celestial phenomena and the weather. Among Roman sources he could use Varro's Rerum rusticarum libri III (Three Books on Agriculture). Vergil, however, puts his own stamp on his subject, especially in his empathetic portrayals of his animal subjects. We see this in the grief of the ox, whose brother and yoke-mate drops dead of the plague beside him (Book 3.515-530). We see it, too, in the family of bees, in whose perfectly regulated society each individual has its assigned task, and who buzz contentedly as they go off to sleep at night (Book 4.176-190).

Happy crops, wedded vines, and thrifty bees

In the Prolog to Book I of the Georgics, addressed to his patron Maecenas, Vergil outlines the subjects of his poem: crops and tillage, viticulture, cattle breeding, and beekeeping. The phrase "wedding vines to elms" refers to the ancient practice of training the grape vines on rows of live trees rather than artificial stakes.

Vergil invokes the rural gods and goddesses, alluding to names both well-known and obscure. He invokes Liber, an old Italian deity of planting, later identified with the Greek Bacchus, and Ceres, goddess of the grain. Faunus ("the favorable god," from faveo) was another old country god, whose voice was heard in the whisper of the winds, later identified with the Greek Pan. the Fauni, like Pan, were portrayed as half goat. Dryads are tree nymphs (from Greek drys "tree," especially "oak"). The "caretaker of the groves" is the hero Aristaeus, who taught mankind farming methods, especially beekeeping.

The Scorpion draws in his claws, yes really!

Finally, in rather cringe-worthy flattery of Augustus Caesar, Vergil invokes the emperor as a future god, asking his divine aid in the welfare of crops and productivity. The phrase "your mother's myrtle" refers to Venus, through Aeneas the mythic ancestress of the Julian gens, into which Augustus had been adopted. The myrtle was sacred to Venus.

Vergil wonders which branch of the divine Augustus will choose, and speculates that he will become a constellation among the stars, where Scorpio draws in his claws to make room for the new occupant. He will be next to Virgo (here called Erigone in reference is to a complicated story in which Erigone, a virgin, commits suicide over the unjust death of her father Icarius). The astronomical speculation, as it happens, is not as silly as it sounds. The constellation now called Libra ("the Scales") was once considered an extension of Scorpio, known as "the Scorpion's Claws," so that the Scorpion took, in Vergil's words, "more than a just proportion of the sky." Vergil deftly associates the new designation of Libra as the "Scales of Justice" with Augustus' fair and just government.

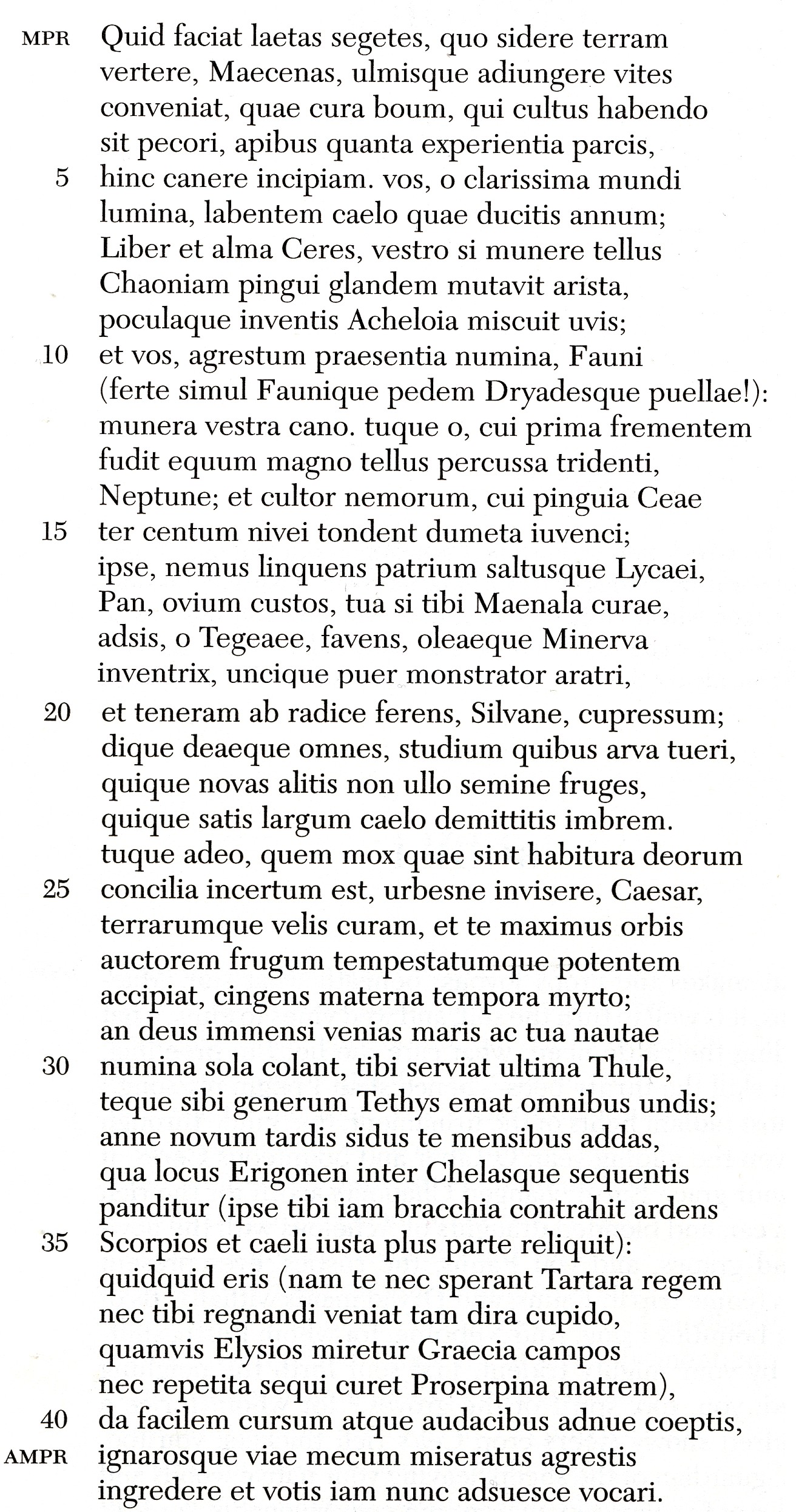

Below, in Latin and English, are the opening lines of Vergil's First Georgic.

Vergil Georgic I 1-42

|

Keeping the crops and the beasts happyWhat makes crops joyous, beneath what star it is appropriateto turn the earth, Maecenas, and to wed the vines to elms, what care the cattle need, what the procedures are for keeping flocks, how much knowledge the thrifty bees require, hence I begin my song. You, o brightest lights of the world, who lead the gliding year through the heaven, and Liber and nourishing Ceres, if through your gift the earth exchanged the Chaonian acorn for the plump ear of grain, and mixed cups of the waters of Achelous with the newly found grapes, and you, Fauns, ever-present divinities of the country people (lift your feet in unison, Fauns and Dryad girls!) I sing of your gifts. And you, o Neptune, for whom first the earth let flow forth the neighing horse when struck by your great trident; and the caretaker of the groves, for whom three hundred snowy steers crop the rich thickets of Cea; and you yourself, Pan, guardian of sheep, leaving your native woods and the ravines of Mount Lycaeus, as you care about your own Maenalus, be present and favor us, o Tegean, and you, Minerva, discoverer of the olive, and the youth who showed us the crooked plow and Silvanus, carrying a young cypress transplant by the roots and all the gods and goddesses, whose zeal it is to guard the fields, those who nourish new fruits sprung from no seed, and those who send widespread rain upon sown crops. And you, especially, Caesar, of whom it is uncertain which councils of the gods will soon have you, whether you prefer to oversee cities and the care of our lands, and that the great globe accept you as powerful author of our crops and seasons, wreathing your brows with your mother's myrtle; or that you come as god of the immense sea, and sailors worship your deity alone, while farthest Thule is subserviant to you, and Tethys buy you for a son-in-law with a dowry of all her waves; or whether you add a new constellation to the tardy months, where a place opens between Erigone [Virgo] and the Claws (blazing Scorpio already draws in his arms and leaves more than a just portion of the sky). Whatever you shall be (for neither does Tartarus hope for you as king nor may such an ominous desire to reign occur to you, although Greece admires the Elysian fields, nor does restored Proserpina care to follow her mother), grant me an easy voyage and nod assent to my bold beginnings, have compassion with me upon country people who do not know their way, advance and become accustomed to be called upon by our prayers. . . . |

Haystacks, from Souvenir of Dakota, the Artesian Wells, by Mrs. A.J. Dickinson, Chamberlain, South Dakota, illustrated by Nelle B. Lockwood, Chamberlain, South Dakota, 1898.

Quotation for March, 2018

For the Beginning of Spring, a Poem From the Appendix Ausoniana |

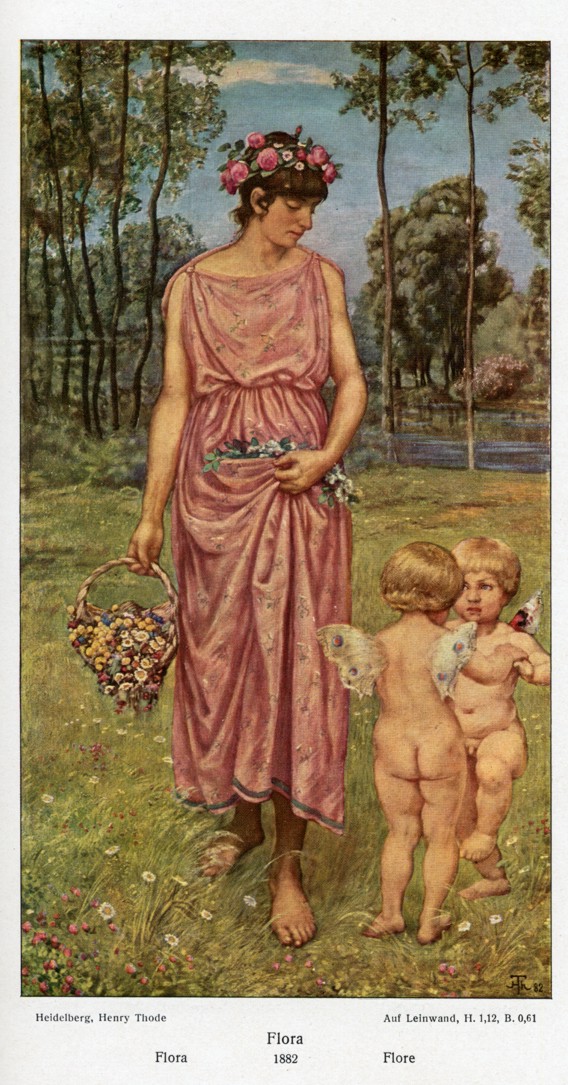

"Flora" by the German artist Hans Thoma (1839-1924). Thoma painted many pictures of idealized rural life, both in his native Bavaria and in Italy. He also painted many mythological and allegorical subjects, as well as realistic portraits of family and friends and several self-protraits — the original "selfies." (Incidentally, Thoma was a relative of mine, an uncle of my grandmother, Virginia Schmid Cooper, an artist working in California. Illustration from Thoma, des Meisters Gemälde in 874 Abbildungen, 1909.)

The spring equinox

Spring is here, as we celebrate Easter, Passover, and the spring equinox, partaking of festivals both religious and secular. Baseball season has begun, too.

For the March Quotation of the Month, we offer a poem from late antiquity that describes a walk through the garden in early morning, with the poet musing on roses that bloom in morning, but fall at night.

The poems ascribed to Ausonius

Our poem has traditionally been ascribed to the poet Ausonius (ca.310-ca.395 A.D.), a native of Burdigala in Roman Aquitaine (modern Bordeaux), who was a tutor to the future emperor Gratian, and later made by him a consul. In some manuscripts the poem is even ascribed To Vergil. More recently, however, it is classed with the Appendix Ausoniana, a group of writings probably not by Ausonius, but from a later period.

Gather Ye Rosebuds

In the opening lines of the poem, which we quote, we find our poet wandering one spring morning in his rose garden, admiring the jewels of frost that cling to shrubs and flowers. But these are jewels that will disappear with the rising sun. His thoughts turn to the roses — does the Dawn steal her colors from the rose, or is it the other way around? For Venus is the goddess of both Morning Star and rose.

In the rest of the poem, he sees the roses in all stages of their birth, lovely maturity, and death, as their petals fall upon the ground. The flower that the Morning Star beheld being born is elderly by nightfall. But from death new life will arise. The poet ends with lines that anticipate Robert Herrick's 17th century "Gather ye rosebuds while ye may," saying "Virgin, gather roses while the flower is new and youth is new,/ and be mindful that your lifetime hurries on."

Below, in Latin and English, are the opening lines of this anonymous poem. The Latin is from the Loeb edition, Vol. 2 pp.277-280. A line appears to be missing from the text after verse 9.

Appendix Ausoniana De Rosis Nascentibus 1-22

|

Dew upon the rosesIt was spring, and the day, brought back by saffron morn,after a biting cold, was breathing with a pleasant feel. A lighter breeze had preceded Dawn's yoked team, moving me to anticipate a day of heat. I was wandering along the square-cornered paths of my well-watered garden plots wishing to be enlivened by the best part of the day. I saw the frost hanging stiff on bending grasses or standing on the tops of garden herbs, and round drops playing together on the broad cabbage leaves. . . . I saw the rose-beds rejoicing, cultivated like those at Paestum, all dewy at the newly risen morning star, bringer of light. Here and there a jewel glishtened white on the frosty bushes destined to perish at the day's first rays. You can debate whether Aurora stole her blush from the rose, or whether she gives it and the risen day dyes the flowers. One dew, one color, one morning for both, for Venus is mistress of the morning star and of the flower. Perhaps also one scent. But the one is diffused high above us on the breezes, whereas this breathes its fragrance closer to us. The goddess of Paphos, shared by star and flower alike, bids both be inhabited by one red color. . . . |

Frülingswiese ("Spring Meadow"), one of Thoma's idealized landscapes. No particular place is named here. (From Thoma, des Meisters Gemälde in 874 Abbildungen, 1909.)

Quotation for February, 2018

For the Lunar Year of the Dog: Odysseus' Dog Argus Recognizes his Disguised Master (Odyssey Book 17) |

Above: Meleager, with his hunting dog, in a Roman statue of the first century A.D. It is one of many copies of a lost bronze sculpture by the fourth century B.C. artist Scopas of Paros. Meleager was a member of the Argonautic expedition and participated in the Calydonian Boar Hunt. In some versions of the statue, as in this one, Meleager is depicted with the head of the boar. (from the Fusconi-Pighini collection, Museo Pio-Clementino, Rome.) photo upoaded to Wikimedia by Jastrow (Marie-Lan Nguyen).Top: Dog Year Paper Cutting, by Fanghong, in Wikimedia.

The Chinese Year of the Dog

In the Chinese Lunar Calendar, 2018 is a Year of the Dog. Depending on the year, the dog may be associated with one of five elements. In 2018 it is associated with the Earth element; others may be Wood Dogs, Fire dogs, Metal Dogs, and Water Dogs. Persons born in a Year of the Dog are independent, energetic, sincere, and loyal. They can also be stubborn. For our Quotation of the Month, we have chosen one of the most memorable dogs in ancient epic, Odysseus' old hunting dog Argus, who greets Odysseus after twenty years, as described in Book 17 of the Odyssey.

Argus, Odysseus' faithful hunting dog, alone recognizes his disguised master

It is one of the most poignant recognition scenes in Homer, as the ancient dog and the disguised hero recognize each other. The humans, however, are oblivious.

Odysseus, having wandered far and suffered much during and after the fall of Troy, at last reaches the shores of his native Ithaca, in disguise as a common tramp. He is taken in, as described in Book 14, by the swineherd Eumaeus, who has taken faithful care of Odysseus' herd in his master's absence. Regularly, he must provide fat boars to the evil Suitors for their banquets, as they feast at Odysseus' expense while wooing his wife Penelope. Eumaeus has built, without telling anyone, a palatial set of pens for the hogs, and even sleeps next to the animals to keep guard over them. Ever cautious, Odysseus does not reveal his true identity to Eumaeus, but spins yarns about his supposed origin, still testing Eumaeus' loyalty.

While Odysseus and Eumaeus are talking, Odysseus' son Telemachus arrives, having made his own journey (in the first four books of the Odyssey) in a fruitless search for his father, while eluding the Suitors' plans to kill him off. Odysseus, while Eumaeus is out of the room, reveals himself to Telemachus, but only after the goddess Athena, changes his appearance from his beggar's clothes. Then, before Eumaeus returns, she changes him back again. At last, Odysseus, led by Eumaeus, proceeds up to the big house, to confront the taunts of the Suitors, who little know the revenge Odysseus will bring upon them.

Argus, his mission accomplished, can die happy

As Odysseus and Eumaeus approach the house, Odysseus sees his old hunting dog Argus — since argos means "brightly shining" or "swift," we might call him "Flash" — he is lying in a pile of manure, covered with ticks, uncared-for and neglected. But Argus alone, the old and tattered dog, recognizes Odysseus, in the form of the old and tattered man. Too weak to get up, he wags his tail and lowers his ears in a playful position. They know each other, but Odysseus cannot give himself away, and turns his head as he wipes away a tear. He asks Eumaeus what happened, and the old swineherd tells him how the young men used to hunt with Argus, but now none of the staff cares for him. (He gets in a dig at the institution of slavery, saying that slaves are unwilling to work because "when a man becomes a slave, Zeus takes away half their qualities.")

Odysseus and Eumaeus proceed into the hall, but Argus, his life's mission accomplished, dies happy, having finally seen his master after twenty years.

Below, in Greek and English, is the scene in the Odyssey in which Argus and Odysseus, unbeknownst to others, recognize each other.

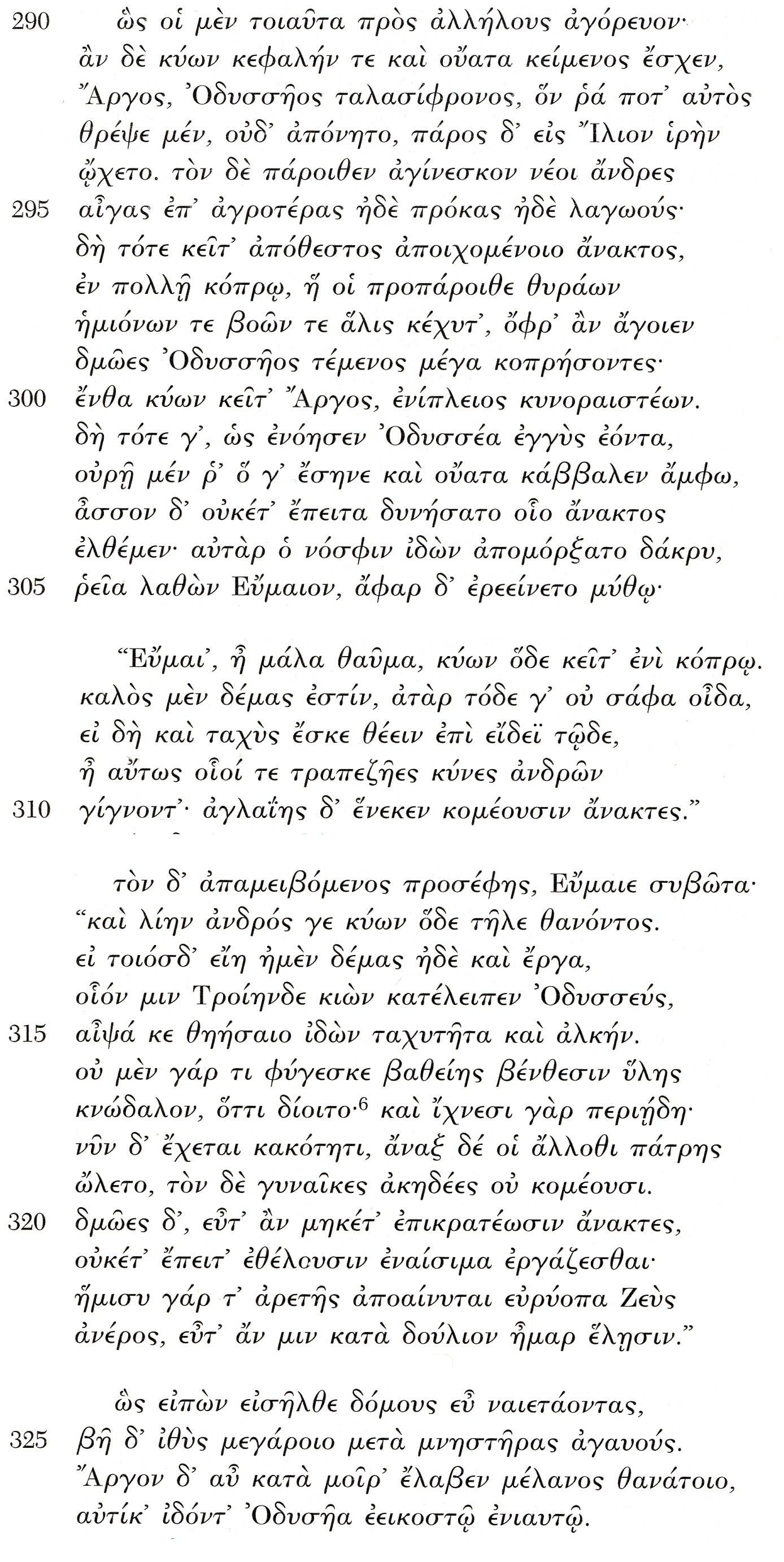

Odyssey 17.290-327

|

Argus, when he and Odysseus have recognized each other, dies happyThus they [Odysseus and Eumaios] spoke to each other.But a dog lying there raised his head and ears, Argos, stouthearted Odysseus' dog, whom he himself had raised, but had never had use of, before going to holy Troy. In former times the young men used to lead him against wild goats and deer and rabbits. But now he lay despised, his master gone, in a heap of manure of mules and cattle, which lay in great quantity before the doors, until the slaves would take it to fertilize the great lands of Odysseus. There the dog Argos lay, full of ticks. Then, when he became aware that Odysseus was near, he wagged his tail and lowered his ears, but had not the strength to approach closer to his master. Odysseus, looking aside, wiped away a tear, easily avoiding Eumaios' attention, but immediately questioned him: Eumaios, this is a very strange thing, that dog lying in the manure. He is beautiful in form, but this I do not clearly know if he was swift at running to match that appearance, or whether he was like what those table dogs become. Their masters care for them as adornments. Then, swineherd Eumaios, you addressed him in answer: "Yes, indeed, this is the dog of a man who has died far away. If he were such in form and in deeds, as when Odysseus left him to go to Troy, you would quickly see his speed and strength. No creature that he chased escaped him in the depths of the deep wood, for he was skilled in tracking. But now he is in the grip of misfortune; and his master has perished far from his native land, and the women, heedless, do no care for him. The slaves, when the masters no longer direct them, no longer are willing to work as they should. For far-seeing Zeus takes away half of a man's qualities, when the day of slavery seizes him." So saying, he entered the well-built house, and went straight to the great hall with the noble suitors. But Argos was taken by the black fate of death, now that he had seen Odysseus in the twentieth year. |

Hades and Persephone at home with the family dog, Cerberus, who seems to be begging for a bone with all three of his heads. Obviously, that much-feared canine, like the legendary Irish wolfhound, is "fierce when provoked, but gentle when stroked." (Illustration from Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.)

Quotation for January, 2018

For Rev. Martin Luther King's Birthday: Petronius Arbiter on Making Your Own Dreams |

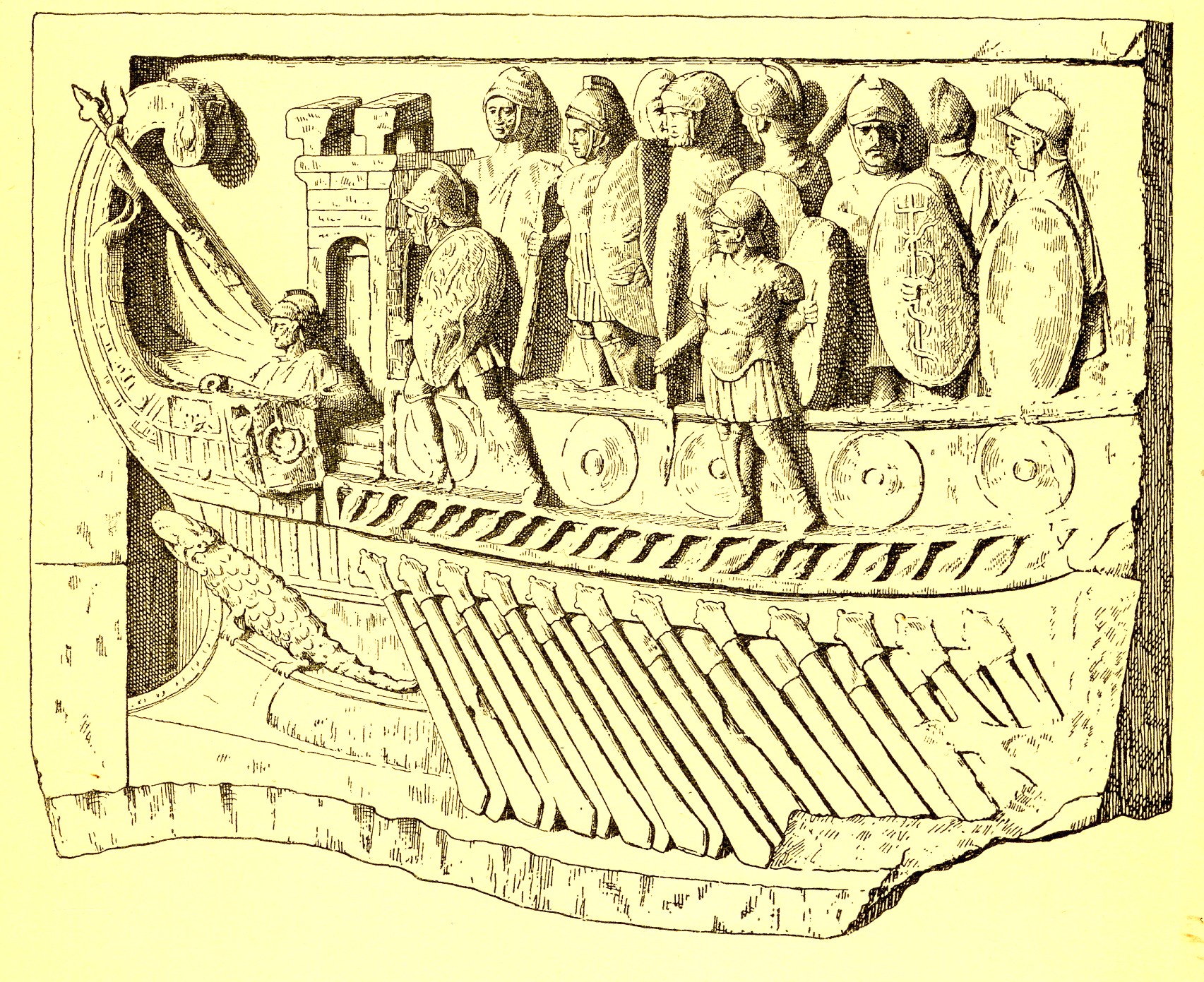

Above: Prow of a Roman two-banked war ship, ca. 50 A.D. From a relief found in the Temple of Fortune at Praeneste, now in the Vatican. Note the leather bags around the ports through which the oars stick from the hull; these keep water from getting in around the oars, but do not constrict their movement. (Illustration from Cecil Torr, Ancient Ships, , 1895.)In Petronius' poem, the sailor may dream that he saves his capsized ship, or that he clings to it as it sinks.

Top: Drawing of Petronius Arbiter from Favissae, utriusque antiquitatis tam romanae quam graecae. . . by Henricus Spoor, 1707, p. 101.

"I have a dream" still resonates

The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose holiday we celebrate the third Monday of every year (in 2018 on his actual birthday, January 15), gave his "I have a Dream" speech at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. The repeated refrain came in an extemporized coda to a prepared speech, in which he was urged on by the great gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who called out to him from the crowd, "Tell them about the dream, Martin!" Inspired, he spoke of the American dream, and of his own dream that one day America would "live up to its creed, that 'We hold these truths to be self evident: that all men are created equal.'"

Together with his other great speech, "I've been to the mountaintop ... and I've seen the Promised Land," delivered on April 3, 1968, one day before his assassination, King's "Dream" speech takes its place among the world's great inspirational orations.

Petronius as an observer of the Roman scene