These are quotations for the year 2016. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2016, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2016 |

Below are quotations for the year 2016. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotation for December, 2016

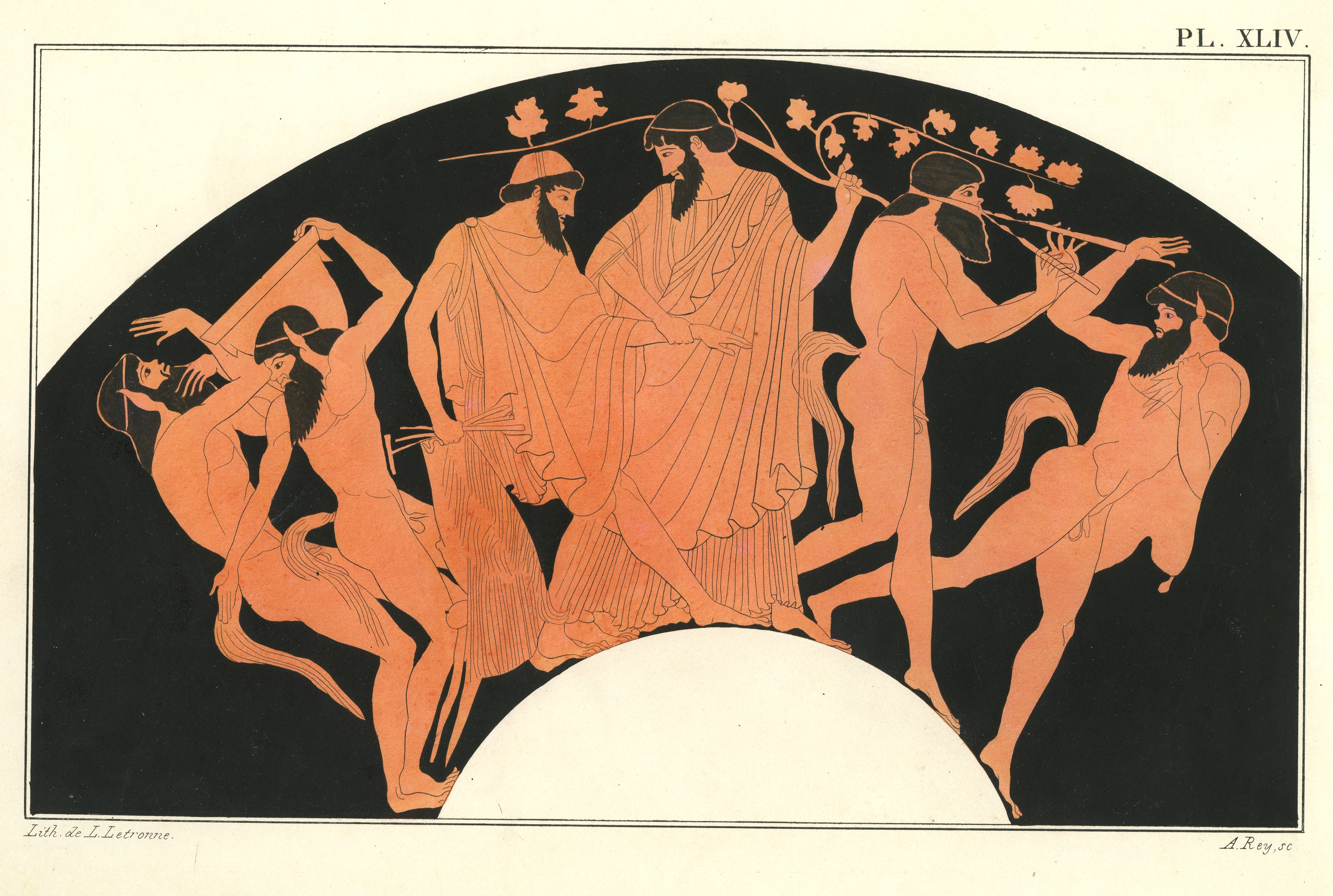

For the Holiday Season, a Celebration of Bacchus (Horace, Odes II.19) |

Dionysus (Bacchus) and satyrs. Lithograph by L. Letronne, ca. 1840.

A season for celebration

This is the holiday season, with Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, New Year's Eve, and New Year's Day all coming in close succession. All occur around the time of the Winter Solstice, celebrated by many as the Sun seems to pause and turn around, giving longer days to the Northern Hemisphere. Despite the fact that many snowy days lie ahead, the returning Sun gives a sense of hope.

Bacchus teaches mountain-dwelling nymphs and satyrs to sing

Merry drinks often accompany the celebration of the winter festivals, and for the end of December and the beginning of January we offer an Ode to Bacchus, god of wine, by the Roman poet Horace. In Ode Book II No. 19, Horace tells how he himself saw Bacchus on a rocky crag teaching nymphs and satyrs to sing (much as the archaic Greek poet Hesiod was taught to sing by the Muses on Mount Helicon — was this Horace's model?). The poet feels both terror and exhilaration at encountering the god, wielding his mighty thyrsus, a rod tipped with a pine cone, sometimes depicted as festooned with ivy and dripping honey. "Bacchus," a Greek name, an alternative to "Dionysus," was the name commonly used by the Romans when they adopted his cult. He was identified with the native Roman deity Liber Pater, the "Free Father," a name also used in the poem.

Three-headed Cerberus wags his tail and licks Bacchus' feet

In the middle verses of the poem (omitted below), Horace describes some of Bacchus' exploits, including the killing of King Pentheus of Thebes, who was torn to pieces by crazed Bacchantes (including his own mother) when he tried to invade their women-only festivities. The story is told by Euripides in his play The Bacchae. The Bacchantes were also known as "Maenads" ("mad women") or "Thyiades" ("orgiasts").

The ode ends with a reference to a myth in which Bacchus descended to the Underworld to rescue his mother Semele. The three-headed guard dog Cerberus, usually fiercely menacing, is won over by Bacchus ("glorious with [his] golden horn," a reference to Bacchus' being sometimes depicted as a bull.) Cerberus wags his tail softly against the god's leg, and licks his legs and feet with all three of his tongues! Now that's some doggy kiss!

Below, in Latin and English, are the opening and final verses of Horace's Ode.

Horace, Odes II.19

|

Bacchus gets a (triple) doggie kiss from Cerberus

I saw Bacchus on remote crags

Although you are said to be more fit for dance and jokes |

Heracles in the Underworld with Cerberus and Erinyes (Furies). Vase from Canosa. One of Heracles' Labors was to bring back the three-headed dog Cerberus from the Underworld. In this picture, Cerberus is in a bad mood! (Illustration from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon.), 1890.

Quotation for November, 2016

For the election of Donald Trump: the Trickster as Prankster and Culture Hero: Autolycus, Odysseus' Grandfather |

The old nurse Eurykleia recognizes the scar on Odysseus' leg and almost gives away his identity.

The President of the U.S. as Trickster

Donald Trump, elected as President of the United States, is admired by some, reviled by others. Although in the public eye every day (by his own choice), he is enigmatic. By turns he insults people and tells lies, yet promises to bring prosperity and jobs back to America. It is difficult to get a handle on who he is and what he stands for, with his chameleon-like ability to change personalities and agendas.

The mythological figure Trump most resembles, in both good and bad aspects, is the Trickster, both as prankster and shape-shifter and as culture hero.

Magical coyotes, spiders and shape-shifting gods

The Trickster, or the Trickster Inventor, is a character found in folk tales all over the world. Coyote is the most widespread Trickster in Native American stories.1 Like many Tricksters, Coyote can take the form of a human or an animal. Like many Tricksters, Coyote lusts after women and food. In some stories, he becomes a fish so that he can enter the bodies of young women swimming in the river. Other animal/human Tricksters take the form of rabbits and foxes. Sometimes the Trickster is outwitted by another Trickster.

The Trickster is also a Creator and Inventor. Among the Lakota and Dakota (Sioux), the principal Trickster is Iktomi the Spider. Iktomi is a liar and a cheat, but he created the world, the Sun and the Moon and the seasons. In some stories, Iktomi created not only the animals but Man and Woman and civilization. The Ashanti of Africa also have a mythic spider or spider/man named Anansi. Tales about Anansi spread to the Caribbean and America. In the U.S. South he became "Aunt Nancy."

Tricksters in Greek mythology

In Greek mythology, Hermes is the preeminent Trickster, and he too is an inventor, a subject I explored in the chapter on "Invention and Trickery" in my book Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns.2 In Homeric Hymn IV to Hermes the poet tells how Hermes, on the day he was born, tricked a tortoise into giving up her shell for him to make a lyre (by promising to make her a singer). He gives the lyre to Apollo, then invents another instrument for himself, the Pan-pipes. He steals the cattle of Apollo, driving them backwards to disguise their footprints, then kills two cows to invent animal sacrifice. Prometheus, another divine thief, stole fire and gave it to mankind, then cheated the gods of their sacrifice by offering only bones wrapped in fat to Zeus. From then on, humans get the good part of the sacrificial meat, the gods get fat and bones.

Greek gods could take the form of animals. Athena, closely associated with the owl, flies off in Odyssey 3.372 as a large bird of prey, perhaps a sea-eagle (phene). Zeus, in his pursuit of sex with women, is by turns a bull (Europa), a swan (Leda), a shower of gold (Danae), and a thunderbolt (Semele).

Autolycus, crafty grandfather of Odysseus

This month, we explore a less well-known Trickster of Greek mythology, Autolycus. The name means "The Wolf Himself." He had no cult, and stories of his parentage are contradictory, but like the stealthy predator, he flits in and out of various stories of other heroes. In some versions, he is the son of Hermes, in others his protegé. He was a master thief, who could steal cattle then disguise his theft by changing their color. He was the grandfather of Odysseus (another Trickster) and appears in stories about Odysseus. In Odyssey Book 19, Odysseus returns to Ithaca in disguise but is almost given away when his old nurse Eurycleia recognizes the scar on his leg, received in a boar hunt, with Autolycus and his sons, "Autolycus, his mother's noble father, who excelled all men in thievery and oaths; the god Hermes himself gave him these powers." (Od.19.394-397).

Odysseus' ancient boar's tusk helmet in the Iliad

Our Quotation of the Month comes from another tale of Odysseus, in Book 10 of the Iliad, where Diomedes, son of Tydeus, and Odysseus go on a spying expedition against the Trojans. As the two men are being armed for their foray, Odysseus is given a helmet stolen long ago by Autolycus and passed along to various heroes, now restored to his grandson Odysseus (but not to its original owners!). The passage provides an extremely accurate description of a boar's tooth helmet that is an anachronism in the Iliad. Its presence explained by its being an heirloom. Boar's tusk helmets of the type described here have been found in Mycenaean shaft graves of the sixteenth century B.C., long before the Trojan War, which has been dated to ca. 1270 B.C. Slices of boar's tusk were laid on a leather cap in alternating directions (see illustration below), and the cap was lined with felt. It is estimated that forty to fifty boars would have to be killed to make one helmet. The leather and cloth parts of the existing helmets have long since disintegrated, but the layers of tusk remain, and the helmets have been restored for exhibit.

Below, in Greek and English, are verses from the Iliad describing the origin of Odysseus' boar's tusk helmet, once stolen by Autolycus.

NOTES:

1. For a collection of Native American Trickster stories, see Richard Erdoes and Alfonso Ortiz, American Indian Trickster Tales, Penguin, 1999.

2. Cora Angier Sowa, Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns, Bolchazy-Carducci, 1984.

Iliad 10.254-282

|

Autolycus stole this helmet, back in the day

Speaking thus, they [Diomedes and Odysseus] put on their terrible armor. |

Boar's tusk helmet from Mycenae, National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Odysseus wore a similar helmet, an heirloom, when he and Diomedes went spying on the Trojan army. Photo by frankfl, from Wikipedia.

Quotation for October, 2016

Autumn Grain: Planting and harvesting in Hesiod's Works and Days |

Hay bales in the snow with mountains in the background, Montana, October, 2016. Photo by C.A. Sowa.

Summer and winter crops

In the American Midwest, the crops have been harvested, and the grain elevators, standing in splendid isolation in the vast plains, are filled. Hay has been baled, and the bales stand in the fields, ready to be trucked away, as we see in the photo above. Snow has begun to fall. Some fields are green, bespeaking winter crops.

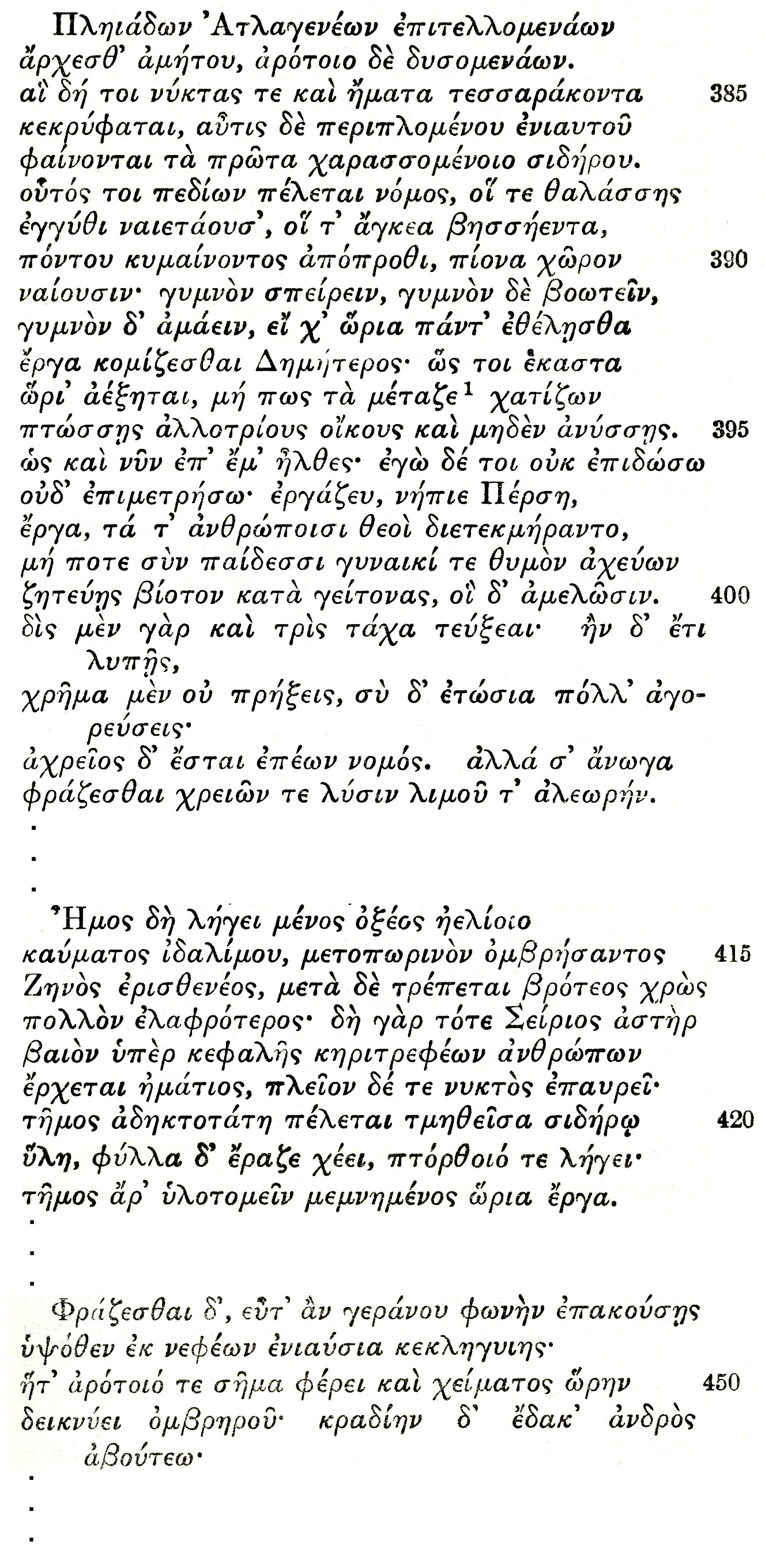

At the bottom of this entry, we see another stark environment, Mount Zagarás in Boeotia, Greece, the ancient Mount Helikon. On its heights the poet Hesiod (ca. 750 B.C.) met the Muses, who taught him to sing. On its slopes stood Ascra, the town to which Hesiod's father had moved from Aeolian Cyme, and in which Hesiod made his home. It was, as the poet tells us in Works and Days v. 640, "bad in winter, miserable in summer, never good." In the Mediterranean climate of Greece, winter grain was the norm, planted in the fall, harvested in the spring. Mythology tells us that Persephone goes underground in fall and joins her husband Hades, King of the Underworld. She rises in spring to rejoin her mother, Demeter, goddess of the grain.

Advice to a no-good brother

Hesiod addressed his Works and Days, an almanac of the farmer's year (with side-trips into myth and other lore), to his brother Perses, a ne'er-do-well who constantly asked Hesiod for financial help.

For our Quotation of the Month, we have chosen verses in which he outlines the autumn's activities: Begin your plowing when the stars of the Pleiades are setting (in November) and harvest when they are rising (early May). This schedule is enhanced by advice to Perses on working instead of freeloading. (In lines that do not appear below, he specifies that he must first get a house, and a slave woman to help with the oxen.) When the autumn rains begin (in October), it is time to cut the wood that will be used to make various useful items; the wood is free of worms at that time.

Hesiod continues (in more lines that are not included here) with explicit directions for making a mortar and pestle for grinding corn and manufacturing a wagon, specifying the type of wood and proper dimensions. Get a pair of oxen, nine years old (because young ones will act up) and a man to drive them (middle-aged, for the same reason). When the crane cries out, it is time to plow.

Below, in Greek and English, are verses from Hesiod describing the farmer's fall schedule.

Works and Days 383-404, 414-422

|

Fall planting, spring harvesting

When the Pleiades, Atlas' daughters, are rising, |

Mount Helikon (modern Mount Zagarás) in Boeotia, on whose slopes Hesiod's town of Ascra stood, and on whose heights he met the Muses, who taught him to sing. (Image from Wikipedia, author GOFAS.)

Quotation for September, 2016

For the Beginning of the School Year, A Mediaeval Student Song about Study (Drink eagerly from the streams of Philosophy!) |

Merry Mediaeval musicians. Image from Gerard Quinn, The Clip Art Book, 1990, source unattributed.

The songs of the Goliards

For the fall semester of the school year, we present, as our Quotation of the Month, a mediaeval student song extolling the study of Philosophy, conceived in its original sense as "Love of Wisdom," including all the subjects to be studied at the University. The best known mediaeval student song is "Gaudeamus Igitur," but there were hundreds of others.

Many of these songs originated in the "goliardic" tradition. The Goliards were wandering poets and singers, originally composed of unemployed clergy and university students, who composed songs, often in Latin, extolling wine, women, and song, and who rebelled against an oppressive church. The origin of the name is obscure, but may be from the singers' adopted persona as followers of the the mythical "Bishop Golias," the name being a form of "Goliath." One of the best known collections of goliardic songs is the Carmina Burana, or "Songs from (the Benedictine monastery of) Benediktbeuern (Bavaria)," some of which were set to music by Carl Orff. A second important collection is the Carmina Cantabrigiensia or "Cambridge Songs," a manuscript containing mediaeval Latin goliardic poems now at the Cambridge University Library. They date, in their surviving form, from ca. 1050 A.D. Our Quotation of the Month comes from the latter collection.

Paths to the fountains of Philosophy

Carmen XXXVII of the Carmina Catabrigiensia, the song Ad mensam philosophiae, is a short poem inviting the student to "thirstily run to the table of Philosophy." (One may assume that not just a thirst for knowledge was involved!) An invitation to "drink from the seven rivers of the tripartite flavor" is certainly a reference to the trivium and quadrivium into which the Seven Liberal Arts were divided. The lower division, the trivium, comprised grammar, logic, and rhetoric. The upper division was made up of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

The second verse of the song names some subjects that "flow" from this fountain: letters, poetry, satire, and comedy. Satire is referred to as lanx satiricorum, the "mixed stew of the satirists," a reference to the origins of the Latin word satura "satire" in the culinary lanx satura or "stuffed dish" of odds and ends. The verse ends by extolling the "Mantuan flute" that brightens the feast, a reference to the poet Vergil, who was from Mantua.

A longer version of the song fills in the curriculum

A longer version of the song (25 verses) exists in another manuscript (Ms. A, Alenšon, Bibl. Ms. 10, saec. XII; Migne PL 151, 729). It describes all the subjects and authors that will be studied by the student. The philosophers Pythagoras, Socrates, and Aristotle are there, as are orators, poets, and dramatists (Cicero, Cato, Ovid, Ennius, Plautus, Terence, et al.) The quadrivium, with its music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy are all mentioned, and Categories and Syllogisms make their appearance. Both the long and the short versions can be found online at the Bibliotheca Augustana web site (Augsburg, Germany). The long version is in Appendix II of the Augustana web page.

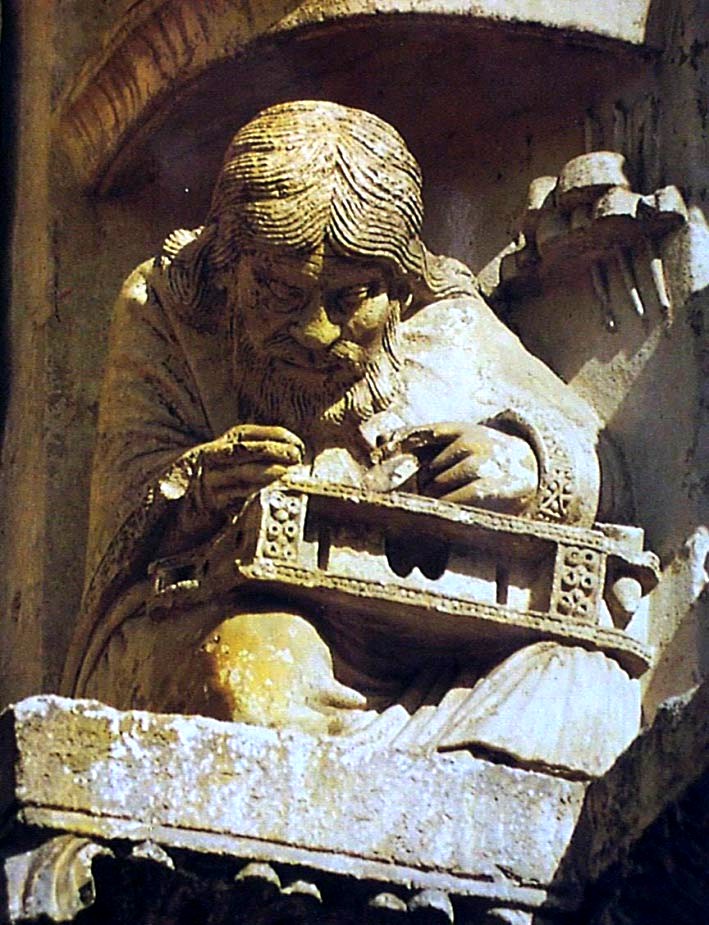

Below, in Latin and English, are the lines of the old student song, as given in the Cambridge manuscript.

Carmen XXXVII

Ad mensam philosophie sitientes currite |

Drink eagerly from the streams of philosophy

Thirsty, run to the table of Philosophy, |

Sculpture said to be of Pythagoras, over one of the doorways of the Cathedral of Chartres. (Photo by Jean-Louis Lascoux via Wikipedia.)

Quotation for August, 2016

For Michael Phelps' record number of Olympic gold medals in swimming, Pindar Olympian I |

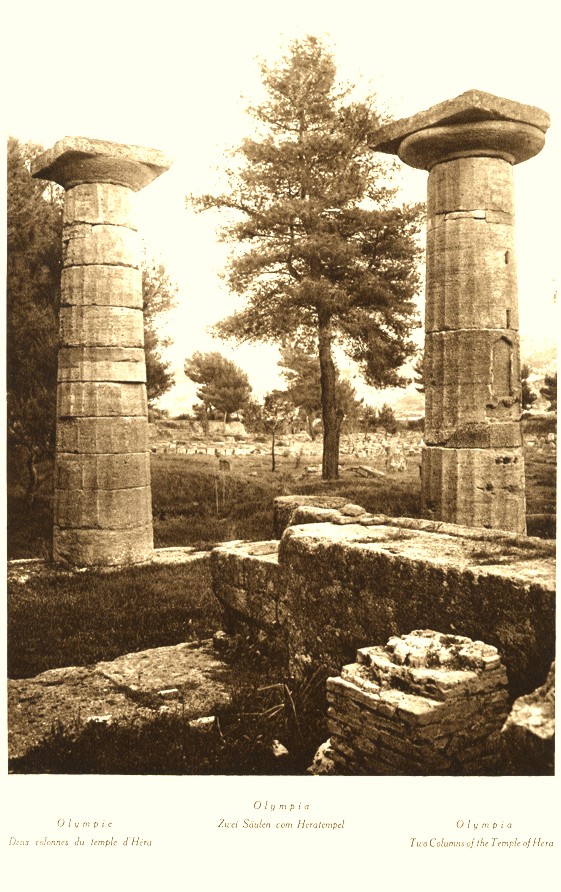

Columns of the Temple of Hera at Olympia. (From Hanns Holdt, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Griechenland, 3rd edition, 1928.)

Breaking a two-thousand-year-old Olympian record

At the Rio de Janeiro Olympics of 2016, swimmer Michael Phelps broke an Olympic record that had stood for 2168 years. By winning 13 individual gold medals in four consecutive Olympic games, Phelps overtook the record set by the runner Leonidas of Rhodes of 12 Olympic titles won in 164, 160, 156, and 152 B.C.

Phelps has won a total of 28 Olympic medals and 23 gold medals (individual and team), and 16 individual medals (all colors). He was the most successful athlete of the Games in four Olympics in a row. Just as in antiquity there were games other than the Olympics, including the Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games, so Phelps holds several world records not only in the Olympics but in the World Championship Games and the Pan Pacific Swimming Championship.

Leonidas of Rhodes won as a runner in the stadion (sprint around the stadium), the diaulos (double stadium), and the hoplitodromos, ("soldier's race," wearing armor). This last-named race began as a military exercise, with runners wearing a helmet and greaves (shin protectors), and carrying a heavy shield. After 450 B.C., the greaves were omitted. Swimming was not a sport in the ancient Olympics, which included track and field events, equine contests such as chariot racing (where the owner typically did not drive the chariot but was merely the owner), boxing, wrestling, and the pankration ("all strengths"), which combined boxing and wrestling and had few rules, and thus was similar to our Mixed Martial Arts.

A wreath of wild olive

In ancient Greece, there were no gold medals, but winners were awarded wreaths, wild olive for the Olympics, laurel for the Pythian, pine for the Isthmian, and wild celery for the Nemean. The wild olive, known in Greek as kotinos, is a species related to, but not identical to, the familiar edible olive. The Olympic wreath was always made from a branch of a specific sacred tree that grew near the temple of Zeus, cut by pais amfithalis (a boy whose parents were both alive) with a pair of golden scissors and taken to the temple of Hera, where the Olympic judges would make it into wreaths for the winners.

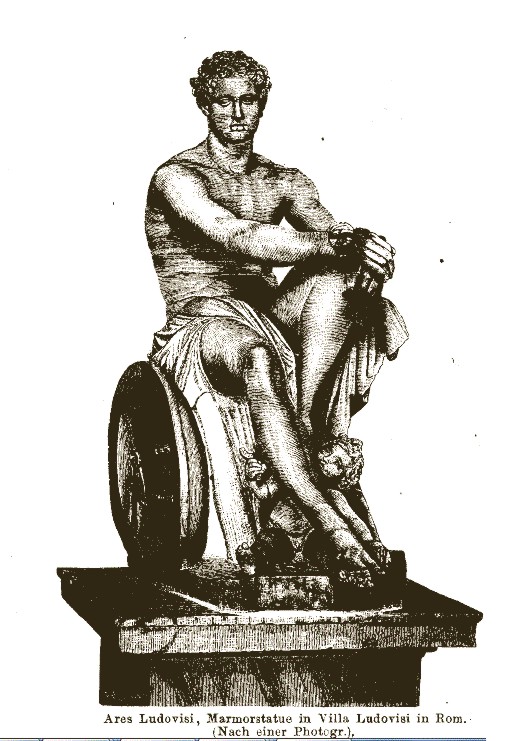

Pindar's golden vision

We have chosen the opening lines of Pindar's First Olympian as our Quotation of the Month. Gold suffuses the victory hymns of Pindar — the golden lyre, the golden Olympic wreath, golden chariots, golden pillars. The First Olympian, perhaps Pindar's best-known poem, was written for the victory of a noble race horse named Pherenikos ("Bearer of Victory") belonging to Hieron, tyrant of Syracuse. It begins by invoking images of water, gold, and the blazing sun in the empty sky, as being those things that are most excellent. Pindar being Pindar, of course we soon leave the present world and are off in the mythic land of Tantalus and of Pelops, beloved of Poseidon, before returning to Hieron's victory. For its praise of water and gold (if not of gold medals for swimming), we have chosen to quote the preface of the poem.

Below, in Greek and English, are the opening lines of Pindar's First Olympian.

Pindar Olympian I, 1-11

|

Finest of all elements

Water is most excellent, and gold shines |

Hoplitodromos, or race in military armor. From an Attic black-figure Panathenaic amphora, 323-322 B.C. Photograph: Marie-Lan Nguyen, via Wikipedia. After 450 B.C., contestants wore only the heavy helmet and shield, but no other armor.

Quotation for July, 2016

For a hot summer, Martial brags (with mixed feelings) of his hillside villa (Epigrams VIII.LXI) |

Horace's Sabine villa near Licenza. (Image from Horace, Complete Works, ed. by Charles Bennett and John C. Rolfe, 1934.) Like Horace, the poet Martial had a summer home outside Rome. Above, coin, ca. 96 A.D., with inscription (perhaps) "Memoriae Domitiane," depicting mule-drawn travelling cart. (Image from "History of Collar Harnessing.")

Getting out of Rome in summer — if you can afford it

In the hot, malarial Roman summer, anyone who could afford to got out of town. The pestilence began in July and continued into December, peaking in September. Vulnerable areas were low-lying valleys between the hills, areas near the Tiber, and swampy lands like the Pontine Marshes.1 The wealthy took refuge in villas in the hills back of Rome. The poet Horace (65 B.C. - 8 B.C.) spoke with affection of his "Sabine farm." Transportation to the suburbs (as well as within the city) was generally provided not by the iconic Roman chariot (these were for warfare, hunting, or racing). It was accomplished by various mundane kinds of carriage, closed or open, private or with many benches like an omnibus, drawn by mules or horses. Martial, a poet of the generation after Horace, alludes to these events in the short poem that is our Quotation of the Month.

Martial, master of the epigram

Marcus Valerius Martialis was born in Augusta Bilbilis (modern Calatayud) in northern Spain sometime between 38 and 41 A.D. Moving to Rome in 64, he lived there some thirty years, then returned to Spain and died there sometime between 102 and 104 A.D. on a rural property presented to him by a wealthy patroness named Marcella. He lived under the emperors Domitian, Nerva, and Trajan, and, just as Horace and Vergil received patronage from the emperor Augustus and the wealthy Maecenas, Martial depended on the generosity of royal and other wealthy patrons for whom he wrote flattering poems. At one point, he was able to acquire a small farm at Nomentum outside Rome and his own mule-drawn carriage so that he no longer had to travel by public "jitney" to his summer home.

An ironic "curse"

Martial is most famous for his Epigrams, short poems, some only a couple of lines, that are observations on human life around him, some obscene, many insulting or satirical. In Book VIII No. LXI Martial describes a man named Charinus, who is so "livid with jealousy" (livet) of the poet that he wants to hang himself. But it is not the poet's fame or fancy clothes that Charinus covets. It is his summer home, and the mule cart that he owns and no longer has to rent. The joke is that the farm was not financially successful, and Martial's "curse" on the jealous man is that he, too, acquire his own mules and summer home.

Below, in Latin and English, is Martial's catty epigram.

Note 1. For more on summer malaria, see J.N. Hays, Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History, 2005.

Martial Epigrams VIII.LXI

Livet Charinus, rumpitur, furit, plorat |

Charinus is very jealous

Charinus is livid with envy, bursting, raging, weeping, |

Horse-drawn carpentum (covered cart). Image from William Smith (ed.) Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 1857.

Quotation for June, 2016

"Sting like a Bee"

In Honor of Muhammad Ali: Boxing at the Funeral Games of Patroclus (Iliad XXIII.664-699) |

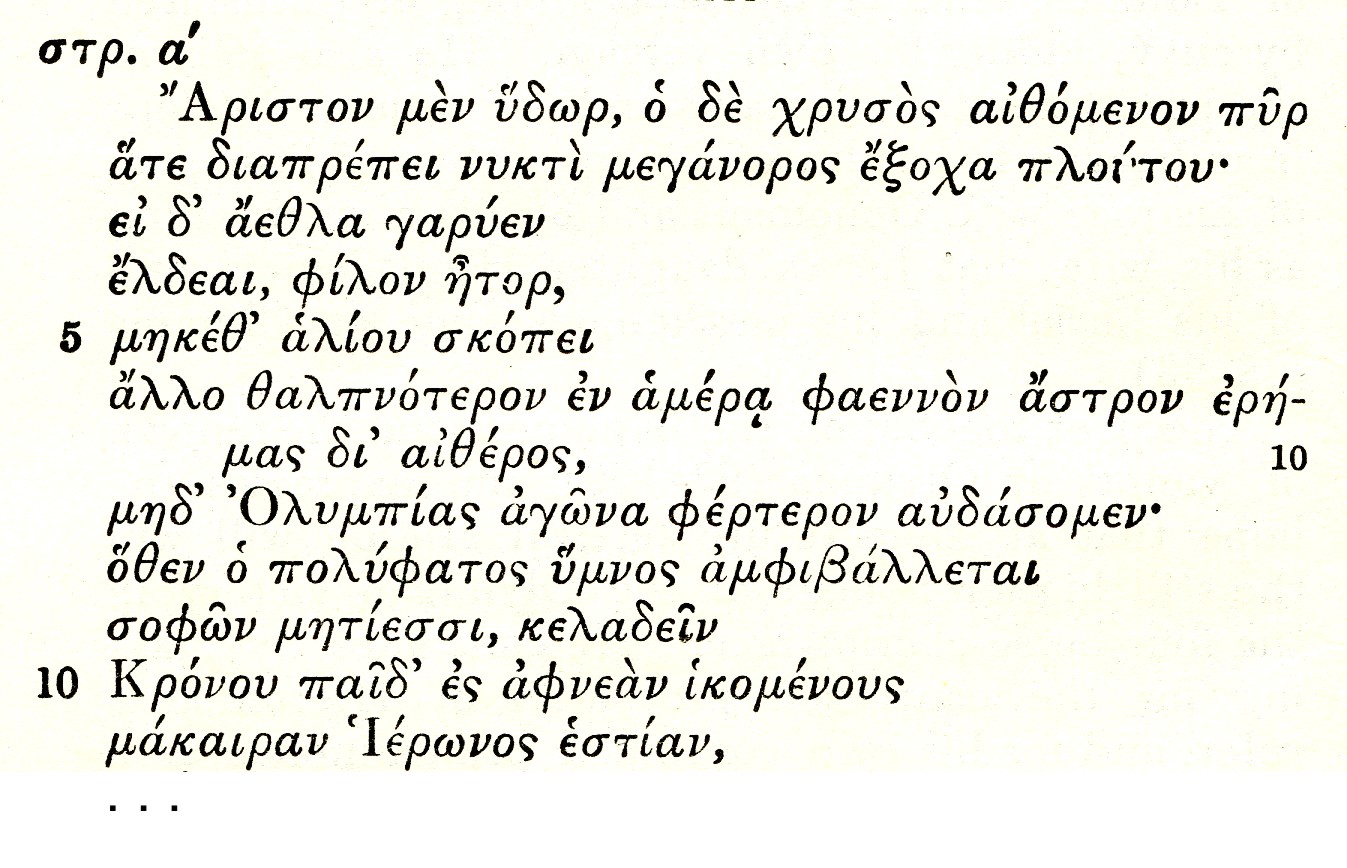

Fresco of boxing boys from the Minoan settlement at Akrotiri, on the island of Thera (modern Santorini), ca. 1600 B.C. (reconstructed from fragments). It is perhaps the earliest known depiction of the use of boxing gloves. (Image from Wikipedia.) Above, gold pendant representing two bees (or wasps) depositing a drop of honey in a honeycomb, from Mallia, Crete, in the Archaeological Museum, Herakleion.

Honoring "The Greatest"

Muhammad Ali, one of the world's greatest boxers, died on June 3, 2016. Controversial and sometimes outrageous, he became an activist for racial justice and for humanitarian causes. Attracted first to the separatist Nation of Islam of Elijah Muhammad, he later joined mainstream Sunni Islam, inspired, like Malcolm X, during a Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, by the great variety of colors and origins of the people he saw there. Born Cassius Marcellus Clay, he changed his name to Muhammad Ali. He refused to be drafted into the Vietnam War, and was banned from boxing for four years that should have been among his most productive. He was known for his whimsical poetry, in which he made fun of his opponents and celebrated himself as "The Greatest." He received two Grammy nominations for spoken word recordings. He developed the art of "trash talking" to new heights, often with colorful descriptions of what he was going to do to his hapless victim. In the art of outrageousness he was inspired by the example of flamboyant professional wrestler "Gorgeous George" Wagner.

"Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee"

Ali's boxing style in his early career featured quick hand and foot work that literally threw his opponents off balance. "I float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, his hand can't hit what his eyes can't see" he bragged before defeating George Foreman. After his enforced layoff from boxing, he developed his "rope-a-dope" style, in which he would absorb punishing blows to the head, tiring out his opponent, then suddenly surprising him with a devastating punch of his own. In 1984, he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, which gradually slowed his body and his quick mouth. It has been suggested the Parkinson's disease from which he suffered in later years was caused in part by the blows to the head that he endured.

Boxing among the Minoans and Mycenaeans

Boxing as a sport goes back to farthest antiquity, as does trash talking, and both arts have probably been practiced as long as there have been humans. The Minoan painting of two boys boxing that stands at the head of this essay is considered the earliest known evidence for the use of boxing gloves. The Hellenistic bronze statue of a boxer shown below exhibits the use of ox hide straps wound around the hands. Ancient boxing was bloody and brutal. There was no protection for the head or face. All these elements are illustrated in Book XXIII of the Iliad, describing the Funeral Games of Patroclus, from which our Quotation of the Month comes.

Trash talk at the funeral games of Patroclus

After the death of his friend Patroclus at the hands of Hector, Achilles becomes a one-man wrecking crew, killing many Trojans and dragging Hector's corpse around the walls of Troy behind his chariot. In his grief, he leaves Patroclus's body unburied, until Patroclus' ghost asks Achilles to bury him, so that he can cross the River and enter the Gates of Hades. A great funeral is held, with spectacular funeral games, including chariot races, boxing, and wrestling. For the boxing match, two prizes are announced. First prize is "a sturdy mule, six years old, unbroken, most difficult to tame." Second prize is a two-handled cup.

A burly man named Epeius comes forward, announcing that although he might not be the finest warrior, as a pugilist he is "The Best" (aristos). (A skilled carpenter, Epeius would go on to build the Trojan Horse, and be one of the soldiers in it.) Epeius announces that he will "rip to pieces the flesh of any opponent and pulverize his bones." Euryalus rises to the challenge, and after a bone-crushing and sweaty encounter, he falls to the ground, but gets up, wobbling. Epeius generously helps Euryalus to his feet, and Euryalus' friends lead him away, spitting blood and dragging his feet, his mind woozy. His companions bring him his second place trophy of a two-handled cup.

Below, in Greek and English, is the description of the fight between Epeius and Euryalus, which has just been announced by Achilles. The "son of Tydeus" is the hero Diomedes, who aids Euryalus.

Iliad XXIII.664-699

|

The winner helps his bloodied opponent to his feet

. . . |

Hellenistic bronze statue of a boxer, from the Thermae of Constantine (3rd to 2nd centuries B.C.). Image from Wikipedia (photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen, 2009). Note the leather straps around his hands.

Quotation for May, 2016

For Commencement, a Youth Assumes the Toga of Adulthood (Ovid Fasti III.771-790) |

Statue of Marcus Aurelius (161-180 A.D.) wearing the toga. British Museum, from Alexandria, Egypt. Photo by Klaus-Dieter Keller, via Wikipedia. A young man assumed the toga of manhood at the festival of Liber Pater, or Bacchus.

Commencement: the original "Toga Party"

This is the season of school and college graduations. The word "graduation" implies the end of a course of study, mostly leading to entry into the next higher level of schooling. But graduation from college or university is also called "Commencement." The word signifies not an end, but a new beginning, a setting forth on the rest of one's life.

In ancient Rome, a young man, usually at age 14, ceremonially removed from his neck the bulla or charm, placed around the necks of children to ward off evil spirits, which he had worn since childhood, dedicating it to the Lares, or household spirits. He also put aside the toga praetexta, or toga bordered in purple, which was worn, with the bulla, by both boys and girls. He would then put on the pure white toga virilis ("manly toga"). This ceremony was performed at the festival of the Liberalia, dedicated to the god "Liber Pater," Father Freedom, an ancient Roman god of fertility, vegetation, and wine, identified with Bacchus and with the Greek Dionysos It was celebrated on March 17, a month or two earlier than our usual Commencement. This was the original Toga Party!

Ovid's tells how boys assume the toga virilis at the Liberalia

Ovid, in Book III of his Fasti, describes the festival of the Liberalia (as usual working in many myths about Bacchus (i.e. Dionysos), including his birth to the Theban Semele, his friendship with satyrs, and his discovery of honey). He also gives a number of explanations of why boys at the Liberalia assume the toga virilis, which he calls the toga libera, or "toga of freedom."

Below, in Latin and English, is Ovid's explanation of the connection between the ritual of putting on the toga and the festival of the Liber Pater. Lucifer is the morning star, therefore, "the Lucifer of Bacchus" is "Bacchus' day." The "torch-bearing goddess" is Ceres (Demeter), who was said to have lighted a pine torch on Mount Aetna while searching for her daughter Proserpina. Ceres, like Bacchus, was a god of crop fertility and increase.

Ovid Fasti III.771-790

. . . |

Why young men assume the toga at the Liberalia

. . . |

Head of Dionysos, from near Smyrna (Izmir), Turkey, second century B.C. At the time of this illustration, the sculpture resided in Leiden, and a missing nose had been replaced. Restored to its originally-discovered condition, it can currently be seen in Berlin's Pergamon Museum. Illustration from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon, 1890.

Quotation for April, 2016

For Earth Day and Arbor Day, an ancient fertility ritual (Ovid Fasti IV.641-672) |

Gaia, rising from the ground, hands Erichthonius ("Totally of the Earth," a future king of Athens) to Athena, as snake-tailed King Cecrops looks on. The Athenians believed that they were "autochthonous," "born from the ground" of Attica, in whose land they had always lived. Snakes were considered intermediaries with the Underworld. Illustration from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie, 1890.

Celebrating our planet on Earth Day and Arbor Day

On April 22, we celebrate Earth Day, when we honor our beloved blue planet and dedicate ourselves to preserving and protecting its gifts. On the last Friday of April we also celebrate Arbor Day, when we plant trees that purify the air and provide habitat for birds, reptiles, and all the other animals with whom we share the planet. Arbor Day is the older of the two holidays, founded in 1872 by Julius Sterling Morton, a Nebraska newspaper editor who later became Secretary of Agriculture under President Grover Cleveland. Almost one hundred years later, in 1970, Earth Day was born with the modern environmental movement. Its success as a popular campaign led to the creation of the United States Environmental Protection Agency and the passage of the Clean Air, Clean Water, and Endangered Species Acts.

To the Greeks, the Earth was Gaia, to the Romans Terra or Tellus. The word tellus is known to us as the origin of the name of the element tellurium, from which come the mineral compounds called tellurides. The old mining town of Telluride, Colorado, today a popular resort, was named for the gold telluride minerals found in various places in Colorado. Ironically, while zinc, lead, copper, silver, and other gold ores were mined in the town's region, no telluride was ever found at Telluride.

King Numa initiates the ritual of the Fordicidia

The ancient Romans performed an April fertility ritual called the Fordicidia. On April 15, fordae, or pregnant cows, were sacrificed to Tellus (forda is related to fero "to carry" or "to bear"). The unborn calves were ritually burned by the eldest Vestal Virgin, and the ashes became an ingredient, along with the blood of a horse and empty bean stalks, in a concoction called suffimen, or fumigating incense. The suffimen was used to purify shepherds and their sheep at another ritual on April 21 called the Parilia, held in honor of a shepherds' god (or perhaps goddess) named Pales. Both rituals were extremely ancient.

Ovid, in his Fasti or Roman Calendar, tells us that the Fordicidia were founded by King Numa, the second king of Rome, a Sabine who succeeded the founder Romulus. Numa was credited with giving Rome many of her laws and religious institutions. Rome at the time was plagued by horrible weather, with droughts followed by floods, with cows bearing premature calves and sheep dying while giving birth. In the legend told by Ovid, Numa betook himself to the sacred grove of Pan, and sacrificing two sheep, lay down upon the fleeces and went to sleep. He was startled awake by the hoofed woodland god Faunus, who tells him to "sacrifice two lives in one heifer."

Numa needs his wife's help to interpret Faunus' answer

Perplexed as to the meaning of this riddling answer, Numa was set straight by the wise counsel of the nymph Egeria, in this version his wife as well as one of his principal advisors. "You are asked for the inward parts of a pregnant cow," she says. Both as a deity and as a woman, she "gets it," where the man does not!

Below, in Latin and English, is Ovid's tale of Numa's perplexity. The "god of Maenalus" is Pan, with whom the Roman Faunus was often identified.

Ovid Fasti IV.641-672: Numa dreams of Faunus . . .

|

. . . and Numa's wife decodes the vision

. . . |

Gaia reclining, with fruits and babies. Illustration from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon, 1890.

Quotation for March, 2016

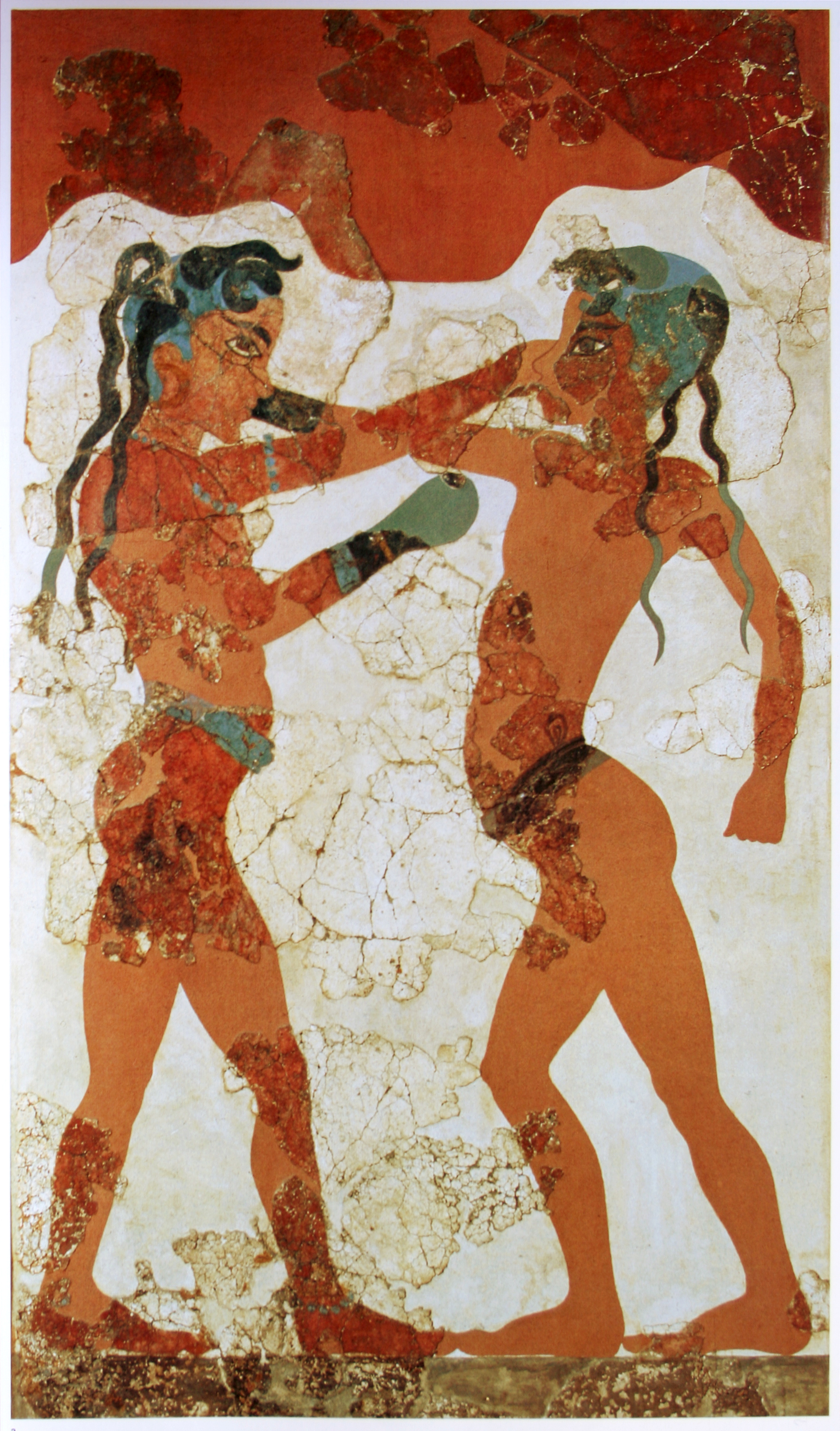

The God of War as Bringer of Peace (Homeric Hymn VIII to Ares) |

The so-called Ludovisi Ares, a 2nd century A.D. marble Roman copy of a late 4th century B.C. Greek statue. Rediscovered in 1622 during the digging of a drain, it was restored by Bernini, who is thought to have added the figure of Cupid at the god's feet. Formerly in the collection of Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, it is now in the section of the National Museum of the Terme located in the Palazzo Altemps in Rome. The above illustration is from Roscher's Ausfürliches Lexikon, 1890.

March was named for the god of war, but can he bring peace, too?

The month of March bears the name of Mars, god of war, appropriately, since we live in a time where questions of war and peace are at the top of the thoughts of many, not least the Presidential candidates. But Mars had other aspects, too. He may have begun as an agricultural deity, whose warlike personality had the aim of warding off both human marauders and the plant diseases that menace farmers' crops, with the ultimate goal of bringing peace.

Mars became identified with the Greek god Ares, who has a similarly complex personality. This month, we bring you the highly unusual Homeric Hymn VIII to Ares, a prayer to the god not just for outward peace but for peace of mind.

An Orphic hymn among the Homeric poems?

The Hymn to Ares is a strange poem, an outlier among the other Hymns, in a totally different style from the old oral tradition they embody. There is no narrative myth, as is found in all the long Hymns, such as those to Demeter and Apollo, and even in some of the shorter ones. The piling up of adjectives and descriptive epithets in the opening invocation has been compared to Orphic poetry. Furthermore, Ares is not invoked only as a shield-bearing god but as the planet we know as Mars, "whirling his fiery sphere among the wonders of the aether in their seven-fold track," that is, among the other planets. The cosmogony resembles that of the Neoplatonist Proclus (5th century A.D.). The poet calls upon Ares to shine down with "a gentle ray." Allen and Halliday (2nd ed. 1963), quoting Pfeiffer, cite the Babylonian belief that when the planet Mars shines brightly it is threatening, whereas if it glows dully, it is auspicious. Allen and Halliday suggest that the compiler of the Hymns, noting that there was no Hymn to Ares in the collection, imported one from another source, although we do not know which.

The Hymn ends with a plea to the god to give the suppliant the "warlike strength" to overcome his baser nature and remain at peace.

Below, in Greek and English, is the complete Hymn. In it, Ares is invoked metaphorically as "father of warlike Nike ('Victory')" and "helper of Themis ('Divine Order')".

TheHomeric Hymn VIII to Ares 1-17

|

A prayer to the Planet of War for peaceAres, exceedingly mighty, filling the chariot, golden-helmeted, |

Bronze figure of Nike (Victory), early Roman Empire. It was found at Cirta (modern Constantine), a city in North Africa, in what is now northeastern Algeria. Cirta was founded by the Phoenicians and taken over by Berbers of Numidia after the defeat of Carthage by Rome. The city later became a Roman colony. The figurine is in the Archaeological Museum of Constantine. Illustration from Roscher's Ausfürliches Lexikon, 1890.

Quotation(s) for February, 2016

Beech leaf (Fagus sylvatica)

Eminent Domain in Ancient Greece and Rome: Vergil's Eclogues and Homer's Odyssey |

First page of 5th century Vergilius Romanus (Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica, Cod. Vat. lat. 3867). Tityrus relaxes under his beech tree as Meliboeus, who has been evicted, trudges by with his goats.

Taking private land for a supposed public good

Presidential candidate Donald Trump, among other outrageous statements he has made, has defended the use of eminent domain, used by government agencies to seize someone's land for the benefit of a private developer. In particular, he defends his use of eminent domain to attempt to seize a long-time resident's house to make a parking lot for a casino in New Jersey.

Eminent domain, the taking of private property by the state for a public purpose, as a phrase, goes back to the term dominium eminens ("supreme lordship") used in the legal treatise De Jure Belli et Pacis, by the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius (1625). In the Unites States, the procedure has long been used for legitimate public purposes such as building a road, but over the years its meaning stretched to include the clearing of land for urban renewal in order to increase the tax base of a city.

Roger Rabbit and the Kelo decision

The expanded concept was permanently enshrined in the infamous Supreme Court decision Kelo vs. City of New London (2005), in which the city of New London Connecticut seized land for the benefit of developers hoping to appeal to employees of Pfizer, Inc. As it turned out, Pfizer closed its plant, and the land is now a dump. Robert Moses, planner and power broker for the city of New York, was a role model for urban renewal enthusiasts in his wholesale destruction of neighborhoods. In Los Angeles, historic districts were destroyed on Bunker Hill and Figueroa Street in the name of freeways and downtown development. The movie Who Framed Roger Rabbit was a fictionalization of this episode. In the film the intended victims are the cartoon inhabitants of "Toontown;" in reality they were poor Mexicans and Filipinos. Among the worst abuses was the destruction of a vibrant Mexican community located in Chavez Ravine, condemned for the purpose of public housing. When public housing was voted down by the City Council, the city found a buyer in Walter O'Malley, who was looking for a place to build a new ballpark for his Brooklyn Dodgers, and the result was Dodger Stadium. Developers offer as an excuse that they offer the original owners "fair market value." This is the price before development, of course. It is always low because the area is impoverished, not the high profit obtained by the developers, which they do not share with the original owners.

The long run of eminent domain in the U.S. culminated in the Kelo decision, and as a result of public outrage many states passed laws reining in the worst abuses. Donald Trump's Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino, for whose parking lot he originally wanted to take Vera Coking's house, closed in 2014 for lack of business. But the concept goes back to antiquity, as can be seen in Vergil and Homer.

Farmers driven out of Vergil's homeland

Vergil's Eclogues can be read as somewhat vapid poems about shepherds and shepherdesses, inspired by the more substantial Idylls of the 3rd century B.C. Sicilian poet Theocritus. But in the First Eclogue he weaves in some subtle and subversive commentary. After the defeat of Brutus and Cassius at the Battle of Philippi in 42 B.C. Octavian (later the Emperor Augustus) and the other Triumvirs seized land in northern Italy around Cremona and Mantua to give to their veterans. According to tradition, Vergil's father was among those whose land was confiscated, but by appealing to Octavian, Vergil was able to get it back. This may, however, be an inference from the story in Eclogue I. Here, an elderly farmer named Tityrus, playing love songs on his flute while relaxing under a tree, is approached by a miserable goatherd, Meliboeus, evicted and homeless. "How did you do it?" the goatherd asks. "A god gave me this leisure," the farmer says. The "god" turns out to be Octavian, to whom the farmer made his appeal, urged on by his latest love, Amaryllis. While much is made in the poem of the largesse of Octavian, for whom, as Augustus, Vergil would later write the Aeneid, Vergil's humanity shows through in his tragic depiction of Meliboeus, as he leaves behind his beloved goats and home for an uncertain future in some distant land. The poem ends with Tityrus offering to let Meliboeus spend the night at his place, since it is late.

Menelaus offers an empty city for Odysseus' use

Homer's Odyssey gives us another point of view. In Book Four, Telemachus travels to Sparta to seek news of his absent father, Odysseus, from King Menelaus. The king has no news of Odysseus, but tells Telemachus a long story about his own adventures. But if he ever sees Odysseus again, he wants to do something nice for him by emptying out some nearby city so that Odysseus and all his family can move in and they can all hang out together. After all, Odysseus went to war to help him get Helen back. However, it seems probable that Menelaus was not inspired only by friendship, but by wanting to bring Odysseus, a powerful king in his own right, closer into Menelaus' own sphere of influence, where he could keep an eye on him! There is no word about what was to happen to the present inhabitants of the evacuated city.

Below, in Latin, Greek and English, are excerpts from Vergil's first Eclogue and the fourth book of the Odyssey.

Vergil Eclogue I 1-18, 64-78

Odyssey 4.168-182

|

EMINENT DOMAIN IN OCTAVIAN'S ROMEYou, Tityrus, enjoy the good life, but I have been evicted and must sell my goats.MELIBOEUSTityrus, reclining beneath the cover of a spreading beech, TITYRUSO Meliboeus, a god gave us this leisure. MELIBOEUSIndeed I do not begrudge you, rather I marvel. Everywhere MELIBOEUSLeaving here, some of us will go among the thirsty Africans, EMINENT DOMAIN IN MENELAUS' SPARTAMenelaus will empty a city and give it to Odysseus.Answering him golden-haired Menelaus spoke:"O my! The son of a man very dear to me has come to my house, one who for my sake endured many trials. And I said that if he came back I would welcome him above all a return to us in our swift ships across the sea. And I would have given him a city for a home and built him a house, bringing him from Ithaca with his goods and his son and all his people, clearing out the inhabitants from a city of those that lie near about and acknowledge me as king. And living here we would have often visited each other. Nor would anything separate us, loving and enjoying each other, until the dark cloud of death covered us. But the god himself must have begrudged us, who made that unfortunate man alone returnless. |

Sparta, site of the Menelaion, shrine of Menelaus and Helen in the ancient Bronze Age city. Mount Taygetus is in the background. Photo by Heinz Schmitz, via Wikipedia. Menelaus offers to clear out a town near Sparta for his good friend Odysseus to move into.

Quotation for January, 2016

On Gun (and other weapon) Violence: Some Advice from Plato (Republic 331.a-d) |

Hoplites fighting hand-to-hand. Amphora, Athens, 530-510 B.C. Art Institute of Chicago. Photo by C.A. Sowa, March 2015.

Keeping weapons away from the mentally ill

Gun violence is a big issue in the 2016 presidential campaign. On one side are defenders of the Second Amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees the right to bear arms, rural citizens who depend on hunting to supplement their food supply, sport hunters, and a variety of individuals and "militia" movements who fear the power of the federal government. On the other side are believers in utopian peace who want to ban guns outright and city-dwellers who have seen the mayhem caused by rival gangs, drugs, and the tragedy of innocent bystanders caught in the crossfire. One thing that just about everyone agrees on is the need to keep guns and other weapons out of the hands of the mentally ill.

The combination of weapons and crazy people is not a new problem, and Plato addressed the issue in his Republic. In the 1970's, when New York was in its darkest days of crime and near-bankruptcy, I once taught Plato in translation to a class of Brooklyn College students whose neighborhood was ridden with crime, and while Plato thought not of guns but of knives and swords, the subject instantly resonated with them.

What is justice?

Plato's Politeia ("Republic") is presented as a conversation between Socrates and a group of friends, narrated by Socrates himself. "I went down yesterday to the Piraeus . . ." it begins innocently. In a spirit of curiosity, he has attended a festival of the Thracian goddess Bendis, and ends up at the house of Cephalus, a retired businessman. They are joined by Cephalus' sons and several others. The conversation turns to definitions of justice. Cephalus has just said that one of the advantages of wealth is that one can go to the other world in good conscience, not having deceived anyone or left debts unpaid.

So, says Socrates, is justice (dikaiosyne) just telling the truth and repaying what you have borrowed? What if you borrow a weapon from someone, and he asks for it back, but he has gone insane (maneis). Would it not be unjust (adikôs) to give it back? Would it not be wrong to tell the whole truth to a madman? (At this point in my class, a lively debate broke out, with one student saying, "Of course you give it back, it's his!" and another replying "Yes, but the dude's crazy!")

From individual justice to the ideal State

Socrates' other friends offer suggestions, and subtly the emphasis changes from "paying someone back" to "giving someone his due," in other words, what he deserves. Polemarchus opines that justice is helping friends and harming enemies, but Socrates counters that it is unjust to harm anyone, since doing harm makes the harmed person a worse man (a concept worth entertaining today, when we consider the effect of long incarceration on the incarcerated). More definitions of justice are discussed, and the dialog progresses from individual justice to political and civic justice, until Socrates (that is, Plato) reveals his description of the ideal state and its governance. It ends with the myth of Er, the man who, having died in battle, is privileged to return from the dead and report what he sees. He sees each soul, preparing for transmigration to a new material body, choosing a new life, with some electing to return as animals and some animals becoming humans. The hero Ajax returns as a lion, the singer Orpheus becomes a swan, and a swan chooses to become a man. Er himself awakes in his own body.

Below, in Greek and English, is part of the discussion between Socrates and his friends.

Plato Republic 331.a-d

|

Justice is not just telling the truth and paying your debtsCephalus:". . . In addition, I believe this is why the acquisition of money is most worthwhile, not perhaps for every man but for one who is reasonable and moderate: Not having to go to the other world in fear of having unwittingly deceived or lied to someone, or having owed sacrifices to some god or money to some man — to this the acquisition of money contributes a large share. It has many other uses, too. But comparing one thing with another, O Socrates, I would claim that for the man of good mind, not least of all, wealth is most useful for this purpose. Socrates:You put that very well, Cephalus, I said. But this thing, justice, shall we shall say it is simply telling the truth and giving back, if someone has received something from someone, or are these things sometimes just, sometimes unjust? I suggest the following: Anyone would say, if a person borrows weapons from a friend who is of sound mind, and if he asks for them back when he has gone mad, that the borrower should not give them back, nor would the person giving back be a just man, nor should he be willing to tell the whole truth to one in such a condition. Cephalus:You speak correctly, he said. Socrates:Then indeed that is not the measure of justice, to

speak the truth and to give back what one has taken. |

Funerary stele of Mnason, Thebes, Archaeological Museum of Thebes, from the museum guide by Katie Demakopoulou and Dora Konsola. "The warrior, stepping barefooted on uneven ground, rushes into battle, his spear in the right hand, his sword and shield in the left." Last decade of the 5th century B.C.

<---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2015 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: