These are quotations for the year 2017. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2017, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2017 |

Below are quotations for the year 2017. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2017

Click on a link to read each quotation

2017

- December, 2017: For the Winter Holidays, Lucretius describes the rotation of the seasons (De Rerum Natura 5.737-750).

- November, 2017: For Thanksgiving and the Holiday Season: the Cornucopia, or Amaltheia's Horn of Plenty (Ovid Fasti 5.115-128).

- October, 2017: For Halloween, a Spooky Story of the Cave of Trophonius (Pausanias 9.39).

- September, 2017: For the Storms and Earthquakes of 2017: Homeric Hymn XXII to Poseidon, Shaker of Earth and Sea.

- August, 2017: For the Eclipse of August 21, 2017, Thales of Miletus (according to Herodotus) Predicts the Eclipse of May 28, 585 B.C.

- July, 2017: For the Dog Days of Summer, Hesiod's Advice in the Works and Days.

- June, 2017: For "Juneteenth," Epictetus on the Irrationality of Slavery.

- May, 2017: For Memorial Day and Fleet Week, the Catalog of the Ships (Iliad Book 2).

- April, 2017: For Earth Day/Earth Month, Gaia in Hesiod's Theogony.

- March, 2017: For Women's History Month, a dedication to Artemis as goddess of childbirth, perhaps by Sappho.

- February, 2017: For Black History Month, Memnon, the Ethiopian hero of the Trojan War (Quintus of Smyrna, Posthomerica Book II).

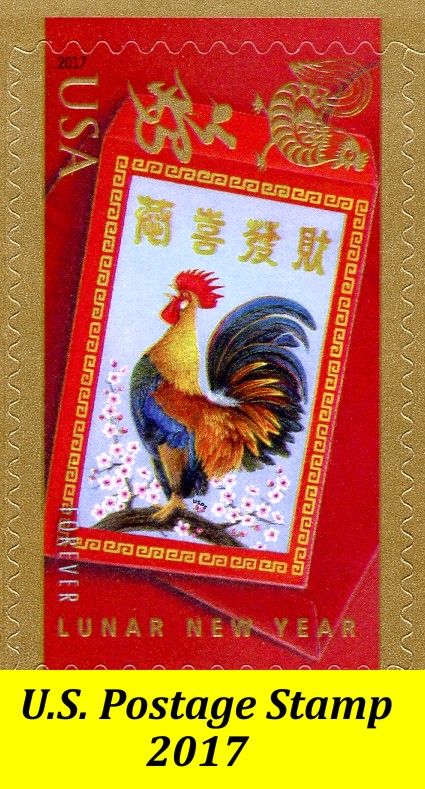

- January, 2017: For the Chinese Year of the Rooster, Socrates' Rooster Offering to Asclepius (Plato, Phaedo).

Quotation for December, 2017

For the Winter Holidays, Lucretius describes the rotation of the seasons (De Rerum Natura 5.737-750) |

The Winter Solstice as a time of new beginnings

Happy holidays! At this time of year we celebrate many different holidays — Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, the Roman Saturnalia, New Year's. All represent a new beginning, a taking stock, a rededication to our purposes and goals. It is the time of the Winter Solstice, when the Sun seems to stand still — perhaps in contemplation? — before returning to its usual business of moving across the sky.

The Romans generally seem to have used the word solstitium (literally "sun standing still") to refer to the Summer Solstice, the longest day of the year, and poets used it to refer to "summer heat." For the Winter Solstice, or shortest day of the year, they used the word bruma, short for brevissima, "shortest."

Lucretius, following Epicurus, explains the universe

Lucretius (ca. 99 B.C. - ca.55 B.C.), in his mighty poem De Rerum Natura "On the Nature of Things.", describes the orderly composition of the universe. We know little about Lucretius, and he is only known to have composed just this one work. He was an admirer of the Greek philosopher Epicurus, founder of the school of philosophy known as Epicureanism. The Epicureans did not, as commonly caricatured, believe in unbridled pleasure, rather, they believed in freedom from pain. They believed in the pursuit of ataraxia, which is often translated as "apathy," but which is more accurately translated as "not being bothered by things." As Bobby McFerrin's song put it, "Don't worry, be happy."

Happiness, the Epicureans believed, comes from understanding the true nature of things, both physical and psychological. Lucretius heaps praise on Epicurus for having delivered mankind from superstition, the kind of misguided belief that led Agamemnon to sacrifice his daughter Iphigeneia to please the gods so that they would provide propitious weather on their voyage to Troy.

Atoms and moon phases; the orderly succession of natural events

Lucretius is rightly praised for his exposition of an early version of the atomic theory, in which the entire universe is made up of indestructable atoms and void. In this, too, he followed the lead of Epicurus, who in turn was influenced by the pre-Socratic philophers Democritus and Leucippus. The word "atom" means "uncuttable" or "indivisible," the early philosopher/scientists being unaware that the atom itself is made up of electrons, protons, neutrons, and even smaller fractions.

Lucretius saw that the entire universe follows a set of orderly patterns, and he saw the importance of believing in direct observation. As a result, however, some of his science is a trifle dubious. Thus, he believed that the sun and the moon are exactly the size that they appear to be.

Lucretius sometimes gives more than one explanation for phenomena, and he may or may not indicate which version he prefers. For example, he gives several different explanations for the phases of the moon. Perhaps the spherical moon shines with light reflected from the sun, and that part that faces the sun reflects more light, as she moves in an orbit lower than the sun. But perhaps she shines with her own light, which is sometimes hidden by another dark body gliding past her. But perhaps she shines with her own light, but only one part lights up, and we only see the light when that side is turned toward us. And finally, perhaps at the end of each day the moon simply vanishes, and another takes its place the following day.

The rotation of the seasons

In the passage we present as our Quotation of the Month, Lucretius describes the sequence of the seasons, from spring to summer to autumn to winter (bruma), "that makes teeth chatter." And so, he reasons, since so many things happen at a fixed time, why not the periodic birth and destruction of the moon?

Below, in Latin and English, is Lucretius' description of the rotation of the seasons. In this passage, Volturnus was a Roman god whose festival was held on August 27. Auster was the hot south wind.

Lucretius De Rerum Natura 5.737-750It ver et Venus, et Veneris praenuntius antepennatus graditur, Zephyri vestigia propter Flora quibus mater praespargens ante viai cuncta coloribus egregiis et odoribus opplet. inde loci sequitur calor aridus et comes una pulverulenta Ceres inde autumnus adit, graditur simul Euhius Euan. inde aliae tempestates ventique sequuntur, altitonans Volturnus et Auster fulmine pollens. tandem bruma nives adfert pigrumque rigorem reddit hiemps, sequitur crepitans hanc dentibus algor. quo minus est mirum si certo tempore luna gignitur et certo deletur tempore rursus cum fieri possint tam certo tempore multa. |

The Rotation of the SeasonsSpring and Venus come, and Venus' winged harbingermarches before them, and in the footsteps of Zephyr mother Flora strewing the path before them fills it all with brilliant colors and scents. Next in place follows arid heat and its companion dusty Ceres and the yearly winds that blow from the north. Then autumn arrives, and with it joyful Bacchus marches in. Then other seasons and winds follow, high-thundering Volturnus and Auster powerful with lightning. At last the shortest day bears snow and winter brings back numb rigidity; there follows painful cold with chattering teeth. So all the less is it to be marvelled at if the moon at a fixed time is born and is destroyed again at a time that is fixed, since the things that can happen at such a fixed time are many. |

Quotation for November, 2017

For Thanksgiving and the Holiday Season: the Cornucopia, or Amaltheia's Horn of Plenty (Ovid Fasti 5.115-128) |

Above: Allegorical sculpture of the River Bug, in Łazienki Królewskie Park ("Royal Baths Park") in Warsaw, Poland. Sculpture by Ludwig Kaufmann, 1855. The god of the river, an important tributary of the Vistula river which flows through Warsaw, is depicted holding a cornucopia full of fruits and flowers. (Photo by C.A. Sowa, September 12, 2015.) Top: Coin image of nymph Amalthea holding baby Zeus. (Image from Roscher, Ausfürliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1884.)

Ouranos, Kronos, Zeus, and hidden children

It is a family drama of sons overthrowing their fathers. In Greek and Roman mythology, Ouranos and Gaia ("Heaven" and "Earth") were the First Couple. They were the parents of many children, including gods, nymphs, mountains, seas, monsters like the Cyclopes, and personifications like Themis ("Law") and Mnemosyne ("Memory"). But, as Hesiod tells us in the Theogony, Ouranos hated his children and buried them deep in Mother Earth. Finally, the youngest child, Kronos, was persuaded by Gaia to castrate his father and free his imprisoned siblings. Kronos cut off his father's genitals and threw them into the sea. From the foam that formed around the severed members, Aphrodite, goddess of love was born. Kronos became king.

But Kronos was no better. Married to the goddess Rhea (another child of Ouranos and Gaia) and afraid that a son would overturn him as he had done his father, he swallowed all his children, one by one. Rhea, on advice from Ouranos and Gaia (who seem to have reconciled), retreated to the island of Crete to give birth to her youngest son, Zeus, and gave Kronos a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes, which he swallowed. Zeus does overthrow his father, who vomits up the stone, followed by his other children, familiar Olympian gods like Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon. A stone, claimed to be the one given Kronos, was exhibited at Delphi, where it was seen by Pausanias. Zeus himself would go on to swallow Metis ("Good Counsel"), his first wife before Hera, so that she could not bear him a son who would overthrow him. She was pregnant with Athena, who was later born from his head. Metis survives within him, to give him advice.1

The infant Zeus, hidden from his father, is suckled by a goat

Hesiod says little of how Zeus was raised in his Cretan retreat, but other poets have filled in the gaps. Many versions exist, but the most common story is that he was born in a cozy cave, either on Mount Ida or on Mount Dikte, was raised by nymphs, and was suckled by an affectionate she-goat. In some tellings, the goat is named Amaltheia, in others, that is the name of the nymph who owned the goat. Somehow, one of the goat's horns broke off (versions differ as to how this happened) and it became filled with fruits, flowers, and all good things, the cornucopia — Cornu Copiae, or "Horn of Plenty," today a symbol of our holiday of Thanksgiving.

Romulus and Remus, Daphnis, and Dolly Parton

Lest we laugh at the barnyard tale, stories of human children suckled by animals are not unprecedented. The most famous, of course, is that of Romulus and Remus, suckled by a wolf. In the 2nd century A.D. Greek novel Daphnis and Chloe by Longus, the boy Daphnis (who is later revealed to be the scion of a wealthy family) is first discovered by a goatherd being suckled by one of his goats, as illustrated at the bottom of this piece. In our own times, the singer and actress Dolly Parton, in her autobiography My Life and Other Unfinished Business, tells how at the age of 3, she was found on the family farm happily nursing among the piglets on one of the sows, much to the mortification of Dolly's mother.

For this month's Quotation of the Month, we present Ovid's telling of the story of Amalthea and Jupiter (the Roman name for Zeus). Below, in Latin and English, is Ovid's story, in Fasti Book 9. Here, "Amalthea" is the name of the nymph, who garlands the horn with herbs and packs it with fruit for baby Jupiter. He, when he becomes king, makes both goat and "fertile horn" into stars.

To prove the story true, you can look in the sky! The goat is the star known as Capella, "Little Goat," the brightest star in the constellation Auriga!

NOTES:

1. For modern versions of the Succession Myth, where successive generations of heroes overthrow their fathers, in films like The Godfather, see my article "Ancient Myths in Modern Movies".

Ovid Fasti 9.115-128Naïs Amalthea, Cretaea nobilis Ida,dicitur in silvis occuluisse Iovem. Huic fuit haedorum mater formosa duorum, inter Dictaeos conspicienda greges, cornibus aeriis atque in sua terga recurvis, ubere, quod nutrix posset habere Iovis. Lac dabat illa deo. Sed fregit in arbore cornu truncaque dimidia parte decoris erat. Sustulit hoc nymphe cinxitque recentibus herbis et plenum pomis ad Iovis ora tulit. Ille ubi res caeli tenuit solioque paterno sedit, et invicto nil Iove maius erat, sidera nutricem, nutricis fertile cornu fecit, quod dominae nunc quoque nomen habet. |

The Horn of AmaltheaThe Naiad Amalthea, renowned on Cretan Mount Ida,is said to have hidden Jupiter in the woods. Belonging to her was the beautiful mother of two kids, conspicuous among the Dictaean flocks, with horns high in the air, curving over her back, and an udder such as the nurse of Jupiter might have. She gave her milk to the god. But she broke one horn on a tree and was deprived of half of her charms. The nymph picked up the horn and bound it with fresh herbs and brought it, filled with fruit, to Jupiter's mouth. He, when he had gained the kingship of heaven and sat on his father's throne, and nothing was greater than unconquered Jupiter, made his nurse, and his nurse's fertile horn, into stars, and the horn even now keeps its mistress' name. |

The infant Daphnis is discovered by a goatherd being suckled by one of his goats. Illustration by Prudhon from the Vizetelly edition of Daphnis and Chloe, ca. 1890, originally in the "Amyot edition" published in French by Pierre Didot in 1800.

Quotation for October, 2017

For Halloween, a Spooky Story of the Cave of Trophonius (Pausanias 9.39) |

Livadia, Boeotia. Within those limestone cliffs is the Cave of Trophonius, where scary things happen when you consult the oracle. (Image by Costas78 from Wikipedia.)

Weird caves

The limestone caves of Greece are places of mystery. From some, sacred springs arise. Many were the haunts of nymphs, and were filled with offerings left by those who wished to earn their favor. Strangest of all were the underground places sacred to immortal heroes, who having disappeared beneath the earth, were thought to live there forever, where they could be consulted as oracles.

Oracular prophets beneath the earth

One of these underground heroes was Amphiaraus, who was one of the Seven Against Thebes, the disastrous expedition in which the sons of Oedipus, Eteocles and Polynices, killed each other over their father's legacy. Amphiaraus, a seer, knew that he would not survive, and, along with his chariot, was swallowed up in the earth. At his sanctuary in Oropus, northwest of Athens, he was consulted for oracular wisdom and for healing, in a similar way to Asclepius. Oedipus himself, as told by Sophocles in his Oedipus at Colonus, disappeared into the earth in the Attic deme of Colonus, northwest of Athens, where his grave became a shrine.

The cave of Trophonius

Weirdest of all is another Boeotian figure, Trophonius, whose cave in the mountains near the Boeotian town of Livadia (ancient Lebadaea) on the banks of the river Hercyna, was a place of nightmarish experiences. It is not clear whether Trophonius (whose name means "Nourisher") was a god, hero, or daimon. According to the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, he and his brother Agamedes built Apollo's temple at the oracle of Delphi. Associated with Trophonius is a nymph named Hercyna ("Defender"), a friend of The Maiden, daughter of Demeter. As told by Pausanias (Book 9), Hercyna was chasing a goose that had escaped into a cave and hidden under a rock. As she lifted up the rock water flowed out, forming the eponymous river, and her cave, too, became a shrine.

Sacred snakes and honey cakes

Trophonius, like Amphiaraus, was associated with healing, and was identified with Asclepius. Within the cave of Hercyna were images identified either as Trophonius and Hercyna or as Asclepius and Health, both holding sceptres entwined with snakes, symbols of Asclepius. In Trophonius' own cave, the suppliant had to carry honey cakes, apparently to appease the resident snakes.

The location of the cave of Trophonius was lost until the Lebadaeans suffered a plague, and the Delphic Oracle told them that a hero somewhere was angry at being neglected. The cave was relocated by following a swarm of bees, who disappeared into a hole in the ground, and Trophonius was appropriately honored.

A scary trip that draws you in

The procedures for consulting Trophonius are described by Pausanias (Book 9.39). The preparation for the visit took several days, during which the suppliant made sacrifices to various gods and took ritual baths in the river Hercyna. At each sacrifice, a diviner examined the entrails of the victim, to make sure that Trophonius would give him a good welcome. When the sacrifices are propitious, he is taken at night to be bathed by two young men, then he is made to drink from two fountains, "Forgetfulness" (Lethe), to forget everything he has been thinking, and "Memory" (Mnemosyne), to remember what he experiences in the cave. Then he puts on ritual garments of linen, and descends to the cave.

The oracle itself consists of a circular structure, shaped like a kribanon, or baker's oven, wider at the bottom than at the top. Attendants bring a ladder for the suppliant to get down into it. There is a little hole in the bottom of the interior wall, through which the inquirer, lying on his back, puts his feet. As he wiggles around trying to get his knees through the opening, he is suddenly sucked in "as if into a whirlpool by a swift river." Once inside, he experiences visual and or auditory phenomena, which are different for each person. Afterwards, he is again sucked out of the same hole, feet first. In an almost catatonic state, he is handed over by the priests to his relatives. Eventually he recovers, and "is able to laugh again." The inquirer is obliged to dedicate a tablet on which he inscribes all he has seen and heard.

The phrase "to go to see Trophonius" came to mean "to go somewhere scary" (as in Aristophanes' Clouds 508). Only one man actually died, Pausanias tells us, but he went under false pretenses, really intending to rob the shrine. His remains were coughed up by the cave through a different opening, not the sacred one.

Pausanias speaks from personal experience

Pausanias assures us that he describes the doings at the cave not from hearsay but from his own personal experience. He does not, however, tell us what he experienced.

Below, in Greek and English, is Pausanias' description of going into the cave of Trophonius.

Pausanias 9.39.10-14:

|

A hallucinatory journey leaves the inquirer terrifiedGoing into the hole, seeing and hearing stuff. . . They have provided no way to get to the bottom. When a man comes to the shrine of Trophonius, they bring him a narrow, lightweight ladder. When the inquirer has descended, there is a hole between the floor and the structure. It appeared to be the width of two spans [i.e. two stretched hands, about 18 inches], and the height seemed to be about one span. The one who descends lies with his back on the bottom holding barley-cakes kneaded with honey and thrusts his feet into the hole and then he himself follows, trying hard to get his knees into the hole. The rest of his body is suddenly pulled in, following his knees, just as the largest and swiftest river will drag a man into its eddy and pull him under. For those who have entered the sanctuary, there is not just one way in which they learn the future, but one person might see something and another hear something. The return from below is by the same mouth, the feet rushing out first . . .Coming back up, unconscious with terror. . . After the inquirer comes back up from Trophonius, the priests seat him upon the so-called throne of Memory, which lies not far from the shrine, and while he is seated there they ask him what he saw and what he has learned. After ascertaining this they turn him over to his relatives. These carry him to the building where he stayed before with Good Fortune and the Good Spirit, taking him there overcome with fright and unconscious both of himself and of those around him. Afterwards, however, his good sense will be no less than before, and laughter will return to him. I write this not from hearsay, but from having seen others, and having myself inquired of Trophonius. Those who have descended to the shrine of Trophonius must dedicate a tablet on which they write all they have heard or seen. . . |

Quotation for September, 2017

For the Storms and Earthquakes of 2017: Homeric Hymn XXII to Poseidon, Shaker of Earth and Sea |

Poseidon, statue on the Lateran Museum, Rome. Image from Seyffert, A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.

A season of tragic storms, earthquakes, and volcanos

The summer and fall of 2017 have been a season of catastrophic storms in the Caribbean islands and along the Texas and Florida Gulf Coast. It also brought earthquakes and volcanos.

Hurricane season began early, with Tropical Storm Arlene in April in the north Atlantic, followed by Bret and Cindy in June, and several other storms and smaller hurricanes in July and August. Then, in quick succession, a half dozen hurricanes, most of prodigious proportions, struck, one after the other. Harvey (Category 4) made landfall on August 26 at Rockport, Texas, near Corpus Christi, then sat for days over Houston and Beaumont, leaving residents unable to escape from flooded homes. Irma (Category 5) made landfall on September 10 in the Florida Keys, then traveled up the center of Florida. Jose (Category 4) went out to sea. Katia (Category 2) made landfall on September 8 at Tecolutla, Mexico as a Category 1. Lee (Category 3) went out to sea. Maria (Category 5) made landfall on September 20 in Puerto Rico. Satellite images from September 8 show three hurricanes, Katia, Irma, and Jose, all revolving like pinwheels in the Caribbean simultaneously. Puerto Rico, devastated and broke, is, as of this writing, still struggling to survive, while the politicians waste time blaming each other.

Earthquakes struck Mexico on September 7 (magnitude 8.1, in Chiapas and Oaxaca), September 19 (magnitude 7.1, in Mexico City Morelos, and Puebla), and September 23 (magnitude 6.1, in Oaxaca).

The Ring of Fire has been active in the South Pacific, with volcanic eruption on Sumatra on September 27, followed by evacuations from Bali and from Vanuatu, an island northeast of Australia, for fear of volcanic activity on those islands. On September 28, the volcano on Vanuatu erupted.

Poseidon, god of storms, earthquakes, and horses

Poseidon, ancient god of the sea and of the waters, was believed by the Greeks to be responsible for both storms and earthquakes. His name is known from the Mycenaean Linear B tablets. The Mediterranean does not have the hurricanes and typhoons of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, but it has sudden storms that seem to come out of nowhere and which sent many ancient ships to the bottom. Storms were thought to be due to Poseidon's anger. When we meet Odysseus in the Odyssey, he has wandered the seas for years because he angered Poseidon by killing his son, the one-eyed Cyclops Polyphemus. Sailors prayed to Poseidon for protection against storms. Poseidon's symbol is the trident, pictured at the top of this article.

According to Homer and Hesiod, Zeus, Hades, and Poseidon, sons of the defeated Kronos, divided the world between them, with Zeus having the sky, Hades the Underworld, and Poseidon the Sea. Poseidon was a god of waters, including springs and streams and the mysterious underground rivers that are found in the limestone crags of Greece. (See L.R. Farnell, Cults of the Greek States Vol. IV, pp. 1-55). It was believed that the movements of underground water were the causes of earthquakes.

The Horse's Spring

Poseidon was associated with the horse, an animal whose strength and wildness were like the raging waters. Just as Poseidon could strike a rock with his trident to make water flow, so the winged horse Pegasus, son of Poseidon, struck the earth with his hoof, creating the spring Hippocrene ("Horse's Spring") on Mount Helicon.

The association with horses was particularly strong in Arcadia, where he had the epithet "Poseidon Hippios." At Phigalia, Pausanias tells of a long-gone ancient wooden statue of Demeter that had a horse's head (Pausanias, Book 8). According to one myth, Demeter, pursued by Poseidon, took the form of a mare. Upon which, Poseidon became a stallion and mated with her.

Thales and tectonic plates

Even the ancient philosophers, including Thales, believed that the world floated in a lake of water, whose movements caused earthquakes. This idea is not so foolish, as modern models of plate tectonics have the plates of the earth's lithosphere move about on the less rigid asthenosphere, causing earthquakes, volcanic activity, and mountain-building.

The Homeric Hymn to Poseidon

Homeric Hymn XXII to Poseidon, our Quotation of the Month, is a short invocation of the god, a prayer to keep sailors safe from storms. It is short, but it covers all his attributes: earthquakes, storms at sea, and horses.

Below, in Greek and English, is the short but succinct invocation to Poseidon that comprises the Hymn to the god.

Homeric Hymn XXII to Poseidon:

|

A prayer for protection of the shipsMover of the earth and of the harvestless sea, Lord of the deep, who also reigns over Helicon and broad Aegae. A twofold honor, Shaker of the Earth, the gods allotted you, to be a tamer of horses and a savior of ships. Hail, Poseidon, Upholder of the Earth, dark-blue-haired, and, O blessed one, with kindly heart bring aid to those who sail. |

Archaic Temple of Poseidon at Isthmia, Isthmus of Corinth, Greece, reconstruction by Kenny Arne Lang Antonsen and Jimmy John Antonsen. Based on information from Excavations at Isthmia — University of Chicago. Archaic Temple at Isthmia. The Archaic Temple at Isthmia: Techniques of Construction, by Elizabeth R. Gebhard. (Image posted on Wikipedia.)Isthmia was the location of the Isthmian Games, dedicated to Poseidon. Along with the Olympic, Pythian, and Nemean, the Isthmian Games were among the foremost ancient contests.

Quotation for August, 2017

For the Eclipse of August 21, 2017, Thales of Miletus (according to Herodotus) Predicts the Eclipse of May 28, 585 B.C. |

Top: Thales of Miletus, as he may have looked.Above: The Antikythera Mechanism, as it looks today, corroded and in pieces, after centuries of burial at the bottom of the Aegean Sea. Pictured is Fragment A (now cleaned up), at the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Composed of interlocking bronze gears, the Mechanism was an early astronomical calculator.

(Images from Wikipedia.)

An eclipse of the sun is an exciting adventure, or it can be a fearful event

A total eclipse of the sun is an exciting event, as the moon neatly fits over the sun like a lid, shutting out its light. On October 21, 2017 such an eclipse was visible over a large swath of the United States. Thousands gathered in remote towns in Oregon and elsewhere to wonder at the phenomenon. In my own backyard, where the eclipse was only partial, the familiar dots of dappled sunlight on the walkway became weird crescents, as gaps between the leaves formed pinhole cameras that projected the shape of the partly covered sun. This can be seen in the photo at the bottom of this article.

But to some, even today, an eclipse is a fearful portent. The National Catholic Reporter for August 11-24 tells us that Father James Kurzynski of St. Joseph Parish in Menominee, Wisconsin felt it necessary to reassure the doubtful that the eclipse was not a "harbinger of end times," but "an opportunity to reflect on humanity's relationship to creation and build stronger bonds with God while enjoying a rare astronomical event."

An eclipse of the sun stops an ancient battle

One such fateful eclipse stopped a battle between the ancient Lydians and the Medes in the sixth century B.C., an eclipse said to have been predicted by the philosopher Thales of Miletus. The story is told by Herodotus in Histories Book I, Chapter 74. In circumstances too complicated to narrate in detail, a band of Scythian nomads had taken refuge among the Medes, an ancient Iranian people. There, the Median King Cyaxares took them in as suppliants and employed them in instructing a group of young men and set them to hunting game. One day, when they returned from the hunt empty-handed, the king treated them with insults. The Scythians retaliated by killing one of their young students, cutting him up, and serving him to the king as they would normally serve freshly killed game. They then fled to Sardis, where they were taken in by the Lydian King Alyattes. Cyaxares demanded the return of the Scythians, Allyattes refused, and war began began between the Lydians and the Medes.

The war went on for five years, and as the sixth year began, a battle was underway, when "day suddenly became night." The combatants decided that this was a good time to quit. Fighting stopped, and a peace was negotiated. The best way to conclude a treaty was always to marry off a princess, so Aryenis, daughter of Alyattes was married to Astyages, son of Cyaxares. (Nobody says what the princess thought.) The treaty was further sealed by both parties making small cuts in their arms and sucking each others' blood.

Did Thales predict the eclipse?

According to Herodotus, the eclipse was predicted by Thales of Miletus, one of the Seven Sages of Greece, who lived circa 624 B.C.- circa 546 B.C. Modern scientists have placed the eclipse, and therefore the battle, on May 28, 585 B.C. based partly on the dates of king lists of the tribes involved.

Modern scholars have questioned whether Thales could have predicted the eclipse, especially since Thales' own dates are rather vague, based somewhat, in circular fashion, on the date of the eclipse itself. (The question was discussed by Alden Mosshammer in "Thales' Eclipse" in Transactions of the American Philological Association Volume 11, 1981 pp. 145-155.)

The Antikythera Mechanism and eclipse prediction

The true reason for solar eclipses was known in antiquity. The device known as the Antikythera Mechanism, discovered in 1900 by sponge divers in a shipwreck at the bottom of the Argean Sea, could, among other things, predict solar and lunar eclipses. Found as a misshapen lump of bronze and wood, it is now recognized as a type of astronomical calculator from the Hellenistic period. Modern imaging techniques show its pieces to be composed of over thirty separate gears that represent the movement of the sun, moon, and planets. The largest fragment is pictured at the top of this article and a schematic representation appears below.

Thales himself was among the first of the Pre-Socratic philosophers to make use of mathematics and geometry in the study of natural phenomena. He is said to have determined the height of the pyramids by comparing the length of shadows cast by a person and by the pyramids.

Below, in Greek and English, is Herodotus' account of the fateful darkening of the sun that ended a war.

Herodotus I.74

|

The sun disappears and a truce is declared |

A schematic recreation of the gears inside the Antikythera Mechanism. A number of proposals have been made as to exactly how the device worked. This schematic is one proposed by James Evans, Christian C. Carman, and Alan Thorndyke (February 2010) in "Solar anomaly and planetary displays in the Antikythera Mechanism" (PDF). Journal for the history of astronomy. xli: 1:39.

The dappled spots of sunlight take on crescent shapes as the gaps between the tree branches become pinhole cameras, projecting the shape of the partially covered sun. Photo by C.A. Sowa, August 21, 2017.

Quotation for July, 2017

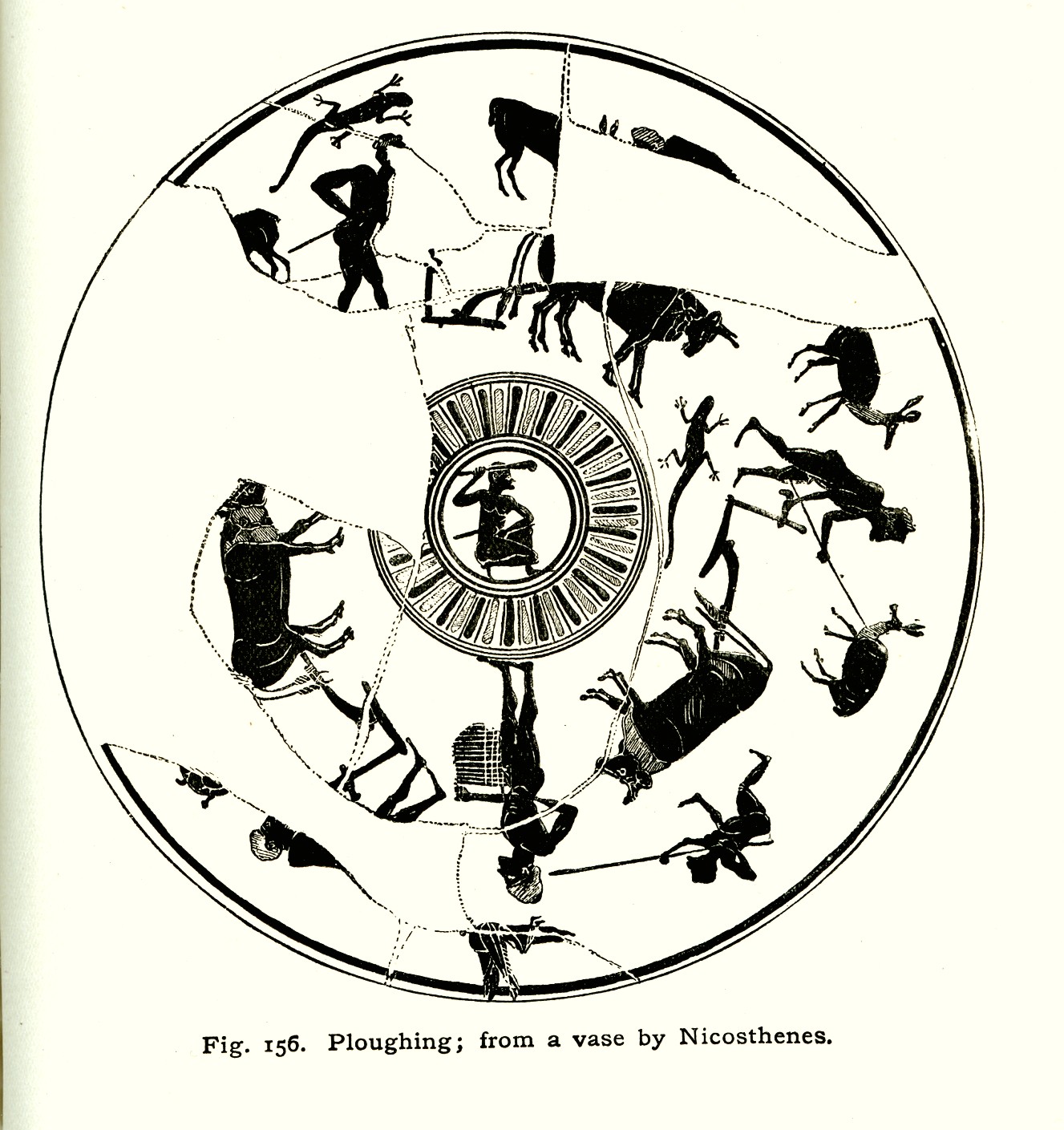

For the Dog Days of Summer, Hesiod's Advice in the Works and Days |

Top: Hesiodic plow, drawing from Leonard Whibley, A Companion to Greek Studies, 1916, p. 637. The drawing follows the description in Hesiod's Works and Days, vv. 427-436. Above, "Ploughing," from a vase by Nicosthenes, Whibley, p. 637.

In the dog days of summer, eat lunch behind a rock to avoid the girls

The Dog Days of summer begin when Sirius, the Dog Star rises. The weather is sweltering, but the wine is at its best. According to Hesiod, the Old Curmudgeon (in his Works and Days), it is also the time when women are at their most lustful and men's knees and head become weak. In the first part of our Quotation of the Month, he advises that the man take his lunch behind a shady rock, with some of that good wine, where, presumably, the girls can't find him. Then he should pour a libation to the deities of the spring.

In late summer, winnow and store your grain, and don't forget to feed the guard dog!

In the second set of quoted verses, it is late summer, and it is time to gather the grain, winnow it, and store it in the big storage jars. (We assume that he is talking about those big man-size clay pithoi, used for storing all sorts of things, found at Bronze- and Iron-Age sites.) The farmer should then let his hired man go and (with more misogyny!) hire a servant girl who is childless, because a servant nursing a child is a pain in the neck. (Note that the word for "nursing a child" is hypoportis, "(a cow) with a calf under her!") The guard dog must be fed well, so that he will keep the burglars ("the man who sleeps by day") away. Then give the slaves some rest, and unyoke the oxen, to give them some rest, too.

In the verses that follow the quoted lines, not quoted here, the farmer must go back to work again in September and October, bringing in the grape harvest and plowing the ground ready for the next crop. The construction of the plow (illustrated at the top of this item) was already described in verses 427-436.

Below, in Greek and English, are Hesiod's words of advice on summer activities.

Hesiod Works and Days vv. 582-608

|

A picnic lunch, then store your grain and unyoke the oxensitting in a tree, pours out its clear song continually from beneath its wings, in the season of exhausting summer, then the goats are fattest and the wine is best, women are most sex-crazed and men are weakest, because Sirius dries up the head and knees, and the skin is dry from the heat. But at that time let there be the shade of a rock and wine from Biblis, and barley bread made with milk drained from goats and meat of a heifer fed in the woods that has not yet calved, and of firstborn kids. Drink the fiery wine, too, while sitting in the shade, when you have satisfied your heart with food. Then turning your face toward the strongly blowing Zephyr, from an ever-flowing spring that runs mud-free, pour three libations of water, but make a fourth libation of wine. Urge your slaves to winnow Demeter's holy grain when strong Orion first appears, in a well-ventilated space on a smooth threshing floor. Then measure it and put it away in storage jars. But when you have put all your livelihood away at the ready in your house, I bid you send your hired man away from the house and seek out a servant girl with no children. For a servant nursing a child is difficult to deal with. And take care of the jagged-toothed dog, don't spare the food, lest the man who sleeps by day take your belongings. Bring in fodder and litter, so that there is enough for the oxen and mules. But then allow some rest for your slaves' poor knees and unyoke the oxen. |

The Vale of Tempe, in Thessaly, northern Greece. A lovely landscape that Hesiod, in scrubby Ascra, could only dream about as he drank his noontime wine. From an old postcard, collection of C.A. Sowa.

Quotation for June, 2017

For "Juneteenth," Epictetus on the Irrationality of Slavery |

An Ethiopian slave breaks in a horse, Archaeological Museum of Athens. Description: "Funerary stele from Attica, right side of a two-panels relief. Pentelic marble, found near the Larisis railway station, date unknown (maybe 4th century BC or 1st century BC). If belonging to the later date, may have been made in honour of king Mithridates of Pontus." (-Wikipedia). Note the panther skin covering the horse like a blanket. Photographer: Marsyas (2006). Above: Epictetus as imagined in the eighteenth century (-Wikipedia).

Celebration of "Juneteenth"

On June 19, 1865, word reached the slaves of Texas that they were free. The news had traveled slowly. On April 9, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, and on June 2, General Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Confederate army west of the Mississippi, surrendered to Union forces, bringing the final end to the American Civil War. The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, had not ended slavery. But it did free those slaves in certain designated rebel states who were able to escape by running away or because the area was taken by Union troops. Many slaves, in fact, escaped to Union lines. The Proclamation did not outlaw slavery or grant citizenship to freed slaves. Slavery would not be outlawed until December 18, 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment went into effect.

On June 19, 1865, federal troops entered Galveston, Texas to take possession of the state and enforce emancipation. Union general Gordon Granger, standing on the balcony of the mansion still known as Ashton Villa, used as Union headquarters, read "General Order No. 3," which begins:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor...

African Americans in Texas have henceforth celebrated the date as "Juneteenth," and observances have spread to other states.

Slavery in antiquity

Slavery in antiquity was regarded somewhat differently than in the United States. Many of the enslaved were war captives or victims of piracy, and might be better educated than their owners. They might become tutors to their owners' children. Freedmen might achieve high professional success. The Roman playwright Terence, whose Latin name was Publius Terentius Afer ("the African") and who lived c. 195/185 - c. 159 B.C., was, with Plautus, one of the two greatest Roman comic dramatists. He was born in north Africa, possibly near Carthage, of Berber descent. He was brought as a slave to Rome by a Roman senator, who gave him an education, then freed him.

The Cynic philosopher Diogenes (c. 412 BC - 323 B.C.) spent time as a slave. Diogenes, who was actually a serious philosopher, a rival and competitor to Plato, was famous for his silly stunts, like living in a large storage jar (often mistranslated as a "barrel") or going around with a lantern "looking for an honest man." When Alexander the Great asked what he could do for him, Diogenes replied, "You could stand out of my sunlight" (to which Alexander said, "If I were not Alexander, I would wish to be Diogenes!") The philosopher was captured by pirates and sold into slavery to a Corinthian named Xeniades, saying that he wished to be "sold to a man who needed a master." He became a tutor to Xeniades' sons.

Another version of the Diogenes/Alexander story, widely quoted and requoted, seems to be a relatively modern fabrication, appearing only in the late seventeenth century. In it, Alexander sees Diogenes looking through a pile of bones, and asks him what he is looking for. Diogenes says, "I am looking for your father's bones and those of my slave," implying that in death we are all equal. A paper for the Yale Law school by Thomas Laqueur traces this tale to conflict of Protestants and Catholics over the veneration of saints' relics.

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus on slavery

In general, slavery was accepted by the classical world as a normal part of the landscape, and its morality or rationality was not questioned. The first surviving statement questioning the reasoning behind the institution comes from the Stoic philosopher Epictetus (c. 50 A.D. - 135 A.D.). Born in Phrygia, he spent his youth as a slave to the wealthy freedman Epaphroditus, secretary to the emperor Nero. The name Epiktetos in Greek simply means "acquired." We do not know what other name he had. Epictetus obtained his freedom in 68 A.D., after the death of Nero, and taught philosophy. His most famous pupil was the historian and philospher Arrian, whose transcriptions of Epictetus' discourses are our only source for Epictetus' thought, since he himself left no writings. These transcriptions take the form of eight books of the Discourses, of which four survive, and the Enchiridion, or "Handbook."

Epictetus quesioned slavery not on moral but on rational grounds. He explains that while we cannot always control external circumstances, we can always control our attitude toward them, using reason. In the Discourses Book 1 Chapter 2, he applies this principle to slavery. If, he says, you hold a chamber pot for your master because if you do not, you will be beaten and you will not be fed, this is a rational choice, as far as it goes. But if you decide that this is not an occupation worthy of you, you must take this into consideration, too. But slavery is also irrational for the slave owner, if he sees that it is intolerable to let another man hold the chamber pot for him.

Below, in Greek and English, are Epictetus' words on rational choice regarding the holding of the chamber pot.

Epictetus 1.2.5

|

To the person who knows his self-worth, slavery is irrational for both slave and master. . |

Alleged portrait of the playwright Terence, from Codex Vaticanus Latinus 3868. This is an illuminated manuscript from the 9th century of Terence's comedies, possibly copied from 3rd-century original. (Image from Wikipedia.)

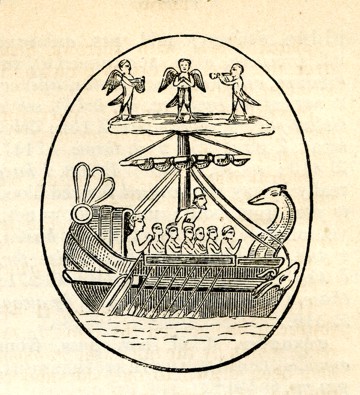

Quotation for May, 2017

For Memorial Day and Fleet Week, the Catalog of the Ships (Iliad Book 2) |

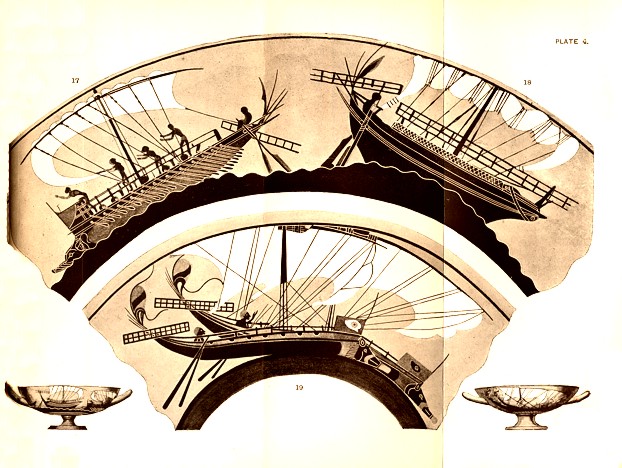

Main illustration: Upper part (Figs. 17, 18) war ship and merchant ship, about 500 B.C. From a painted vase found at Vulci, in Etruria. Lower part (Fig.19) two war ships, about 500 B.C. From a painted vase by Nicosthenes found at Vulci. Illustrations from Cecil Torr, Ancient Ships, 1895. Small inset picture: the Sirens singing to Odysseus from the rigging of his ship. Illustration from Autenrieth's Homeric Dictionary, 1876. The comment is made: "The cut, from an ancient gem, represents them as bird-footed, an addition of later fable; for Homer, they are beautiful women."

A gathering of ships

Fleet Week is a chance for the Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard to show off their ships and stage spectacular air shows. It is celebrated in summer in ports around the U.S. In New York, it takes place the week of Memorial Day; in Portland, Oregon it is in June, in conjunction with the annual Rose Festival, and in San Francisco it will be in October. Other cities include San Diego, Port Everglades, and Seattle. Summer is also a time when coastal inhabitants' thoughts turn to enjoying the water, whether from a boat or on the beach.

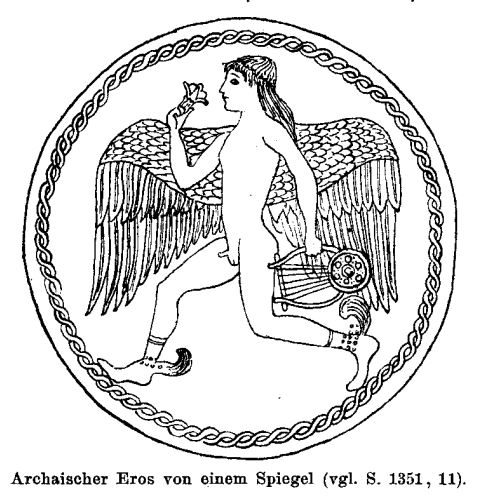

For the Quotation of the Month for May we present the most famous Fleet Week of Greek epic, the Catalog of the Ships from Book 2 of the Iliad (vv. 484-759). The Greek army is drawn up before the walls of Troy. They have been there for nine years, and many of the soldiers are ready to go home. But speeches from Odysseus (inspired by Athena), Nestor, and Agamemnon restore their courage, and they prepare for a fight. There follows the great Catalog, enumerating the leaders of each contingent, with the number of ships provided by each, including numerous stories and digressions about the many heroes. The Catalog of the Ships is followed by the Catalog of the Greek horsemen and the Catalog of the Trojans and their allies.

The Greek ships that went to Troy

The magnitude of the Greek army is matched by the magnitude of the Catalog, which weighs in at 275 verses. To quote Homer, "If I had ten tongues and ten mouths, and an unbroken voice, and the heart within me were bronze," I could not include the entire Catalog here. Homer had the advantage of help from the Muses, whom he invokes as he begins his narration. All the heroes are here, including Agamemnon of Mycenae, Menelaus of Sparta, Nestor of Pylos, Odysseus of Ithaca, Idomeneus of Crete, Ajax of Salamis, along with the Athenians, the Cretans, and those from Arcadia, Argos and Tiryns, and all the rest.

I include here only the invocation to the Muses and the first two contingents, the Boeotians and Minyan Orchomenus, the latter usually regarded as part of Boeotia, but here given its own entry.

In the Iliad, the Theban wars are just a memory

The Boeotian entry is most interesting for what it does not include. Many of the town names are little known, such as Hyria, Schoenus, Peteon, Ocalea, and Medeon — who were they, anyway? A few have their own fame. Plataea became famous later as the site of the Battle of Plataea (479 B.C.) in which the Greeks finally drove the Persians out of mainland Greece in the Second Persian War. Onchestus is known to us from the Homeric Hymn IV to Hermes, in which the Old Man of Onchestus tattles on the infant Hermes, whom he has seen driving the cattle of Apollo, which he has stolen, backwards to disguise their footprints.

But where is the glorious seven-gated city of Thebes? Only "Lower Thebes" (Hypothebai) is named. The city of Cadmus, of Semele and Dionysus, of Oedipus, of Antigone, of the heroes of the Seven Against Thebes — that city is but a memory. These are stories famed in epic and drama second only to the Trojan War itself (although the Argonauts and Jason and Medea are close behind). Bronze Age Thebes was destroyed by the Epigonoi, the "After-born," sons of the heroes of the first Theban War. Thebes would be reborn in historic times as one of the great cities of Classical Greece, but by the time of the Trojan War, the powerful old Theban stories were themselves history.

Below, in Greek and English, are the opening lines of the Catalog of the Ships and two contingents of Agamemnon's army and navy, as described in the Iliad, Book 2, vv.484-516.

Iliad 2.484-516

|

The ships that left for Troy— for you are goddesses, you are present, and know all things, but we only hear the report, and know nothing — who were the leaders of the Danaans and their kings. Their multitudes I could not tell or name, if I had ten tongues and ten mouths, and an unbroken voice, and the heart within me were bronze, if the Olympian Muses, daughters of aegis-bearing Zeus, did not remind me how many came beneath Ilion. Now I will tell of the captains of the ships and all the ships together. The Boeotians were led by Peneleos and Leïtus, and Arcesilaus and Prothoënor and Clonius. They were those who lived in Hyria and rocky Aulis and Schoenus and Scolus and Eteonus with its many ridges, Thespeia and Graea and Mycalessus of the broad dancing-places, and those who dwelt around Harma and Eilisium and Erythrae, and they that held Eleon and Hyle and Peteon, Ocalea and Medeon, the well-built city, Copas and Eutresis and Thisbe, with its many doves, they who held Coroneia and grassy Haliartus and Plataea, and who lived in Glisas, and those who held Lower Thebes, the well-built city, and holy Onchestus, the shining grove of Poseidon, and who held Arne, rich in grapes, and Mideia and sacred Nisa and farthest Anthedon. Of these there came fifty ships, and in each one went one hundred and twenty young men of the Boeotians. Of those who lived in Aspledon and Minyan Orchomenus the leaders were Ascalaphus and Ialmenus, sons of Ares, to whom, in the home of Actor, son of Azeus, Astyoche gave birth, revered maiden, when she went to her upper chamber, conceiving them of mighty Ares, for he lay with her in secret. With them were ranged thirty hollow ships. . . . |

Two war ships in action, about 550 B.C.From a painted vase by Aristonophos found at Caere in Etruria. Illustration from Cecil Torr, Ancient Ships, 1895.

Quotation for April, 2017

For Earth Day/Earth Month, Gaia in Hesiod's Theogony |

Gaia Kourotrophos (Earth nourisher of children). Image from Roscher, Ausfürliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1884. The aconite, in the inset photo above, which I took in my garden, is the first flower to come out of the earth in spring, even before the crocuses. Sometimes it gets covered by a late snow, but it always bounces back. The bees love it.

How the universe began

It all begins with Chaos, Earth, and Love. Our Quotation of the Month for April is taken from Hesiod's Theogony, his epic on how the universe came to be. The Theogony (ca. 750 B.C.) can be described in shorthand form as the genealogy of the gods, but it is more than that. It is a dizzying carousel of stories of gods, goddesses, nymphs, monsters, storms, winds, and bizarre phenomena, and their descent from and battles with each other.

Hesiod took his tales from many sources — previous epics, ritual cults sacred to local features like mountains and springs, old stories — and strung them together to make a coherent narrative. The Succession Myth, of successive generations of monarchs (in this case gods: Ouranos (Heaven), Cronos, Zeus) deposing each other has parallels in other Near Eastern mythologies — Phoenician, Hurrian, Babylonian, Hittite. Sometimes, it was surmised by M.L. West in his edition of the Theogony, Hesiod (or some predecessor) simply used his own imagination to make up names to fill out his lists of nymphs and multiplicities of Muses, Cyclopes, Hours, sea goddesses, and the like. He weaves in an array of stories, like the story of the first woman, who brought nothing but trouble. He used this story again in his Works and Days, where he gives her the familiar name: Pandora.

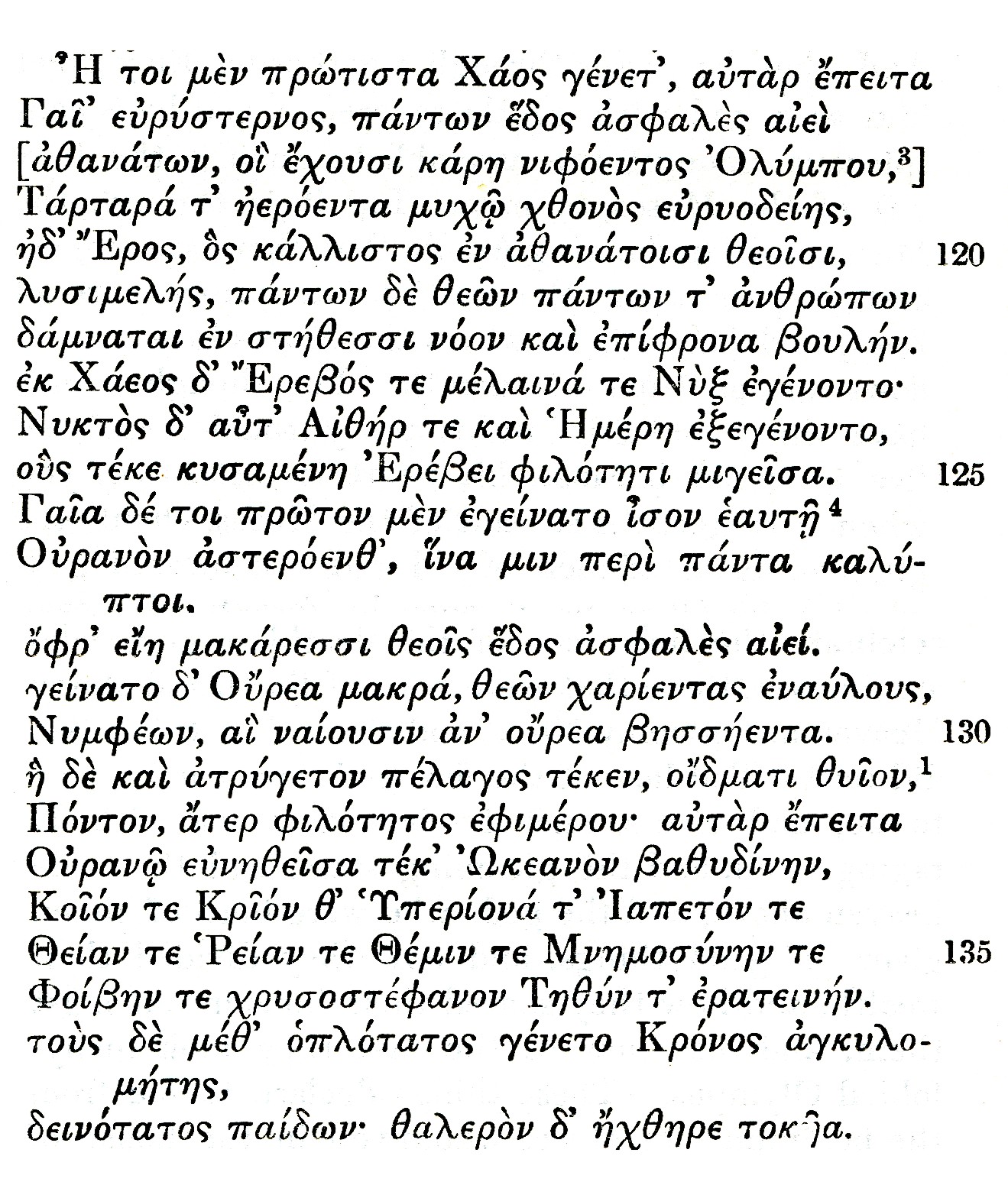

Chaos, Earth, and Love

First came Chaos, then Earth, then Tartarus, and Eros. There is much speculation about the word "Chaos." We moderns are tempted to see in this the Big Bang and the swirling dust that coalesced into stars and planets, but we can't be sure how Hesiod conceived it. Was it simply the Yawning Gap, a great chasm, or some murky dark substance? We can't be sure. Next came Gaia, the Earth, supporter of all life and Tartarus, the nether world, hidden in the dark places of Earth. Then Eros, or Love, "most beautiful of the gods, who makes men weak-kneed and makes them lose their minds and judgment."

Earth herself gave birth to Ouranos (Heaven), by whom she bore many gods and a few monsters, including the one-eyed Cyclopes. Ouranos had a bad habit of stuffing all his children back into Earth, who groaned in pain. Finally her son Cronos took a sickle and cut off his father's private parts and threw them into the sea, separating Heaven and Earth. Around the severed genitalia the white foam spread. It was from this sea foam that Aphrodite, goddess of desire and fertility, was born.

The generations continue

Cronos, married to Rhea, was the father of many well-known gods, including Zeus, Hera, Demeter, Hades, and Poseidon. But Cronos, too, had a bad habit, of swallowing all his children, lest one of them depose him. So when Zeus, the youngest, was born, he was hidden in a cave, while Cronos was given a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes, which Cronos swallowed. He threw up the stone, then vomited up all the children he had swallowed, and Zeus indeed became king of the gods.

Zeus' first wife (before Hera) was Mêtis ("Good Counsel"). Metis became pregnant with Athena, but Zeus was told that Metis' next child would be a son who would depose him, so he stuffed pregnant Metis into his belly, thus not only ensuring his kingship but also making sure that the wise goddess would be there to give him advice. Later (in what may have originally been a separate myth), Zeus gave birth to Athena from his head. By this time Zeus was married to Hera, who was angry at him for producing the wise Athena without her. So on her own she gave birth to the craftsman god Hephaestus.

And so on! The stories are too many to summarize here!

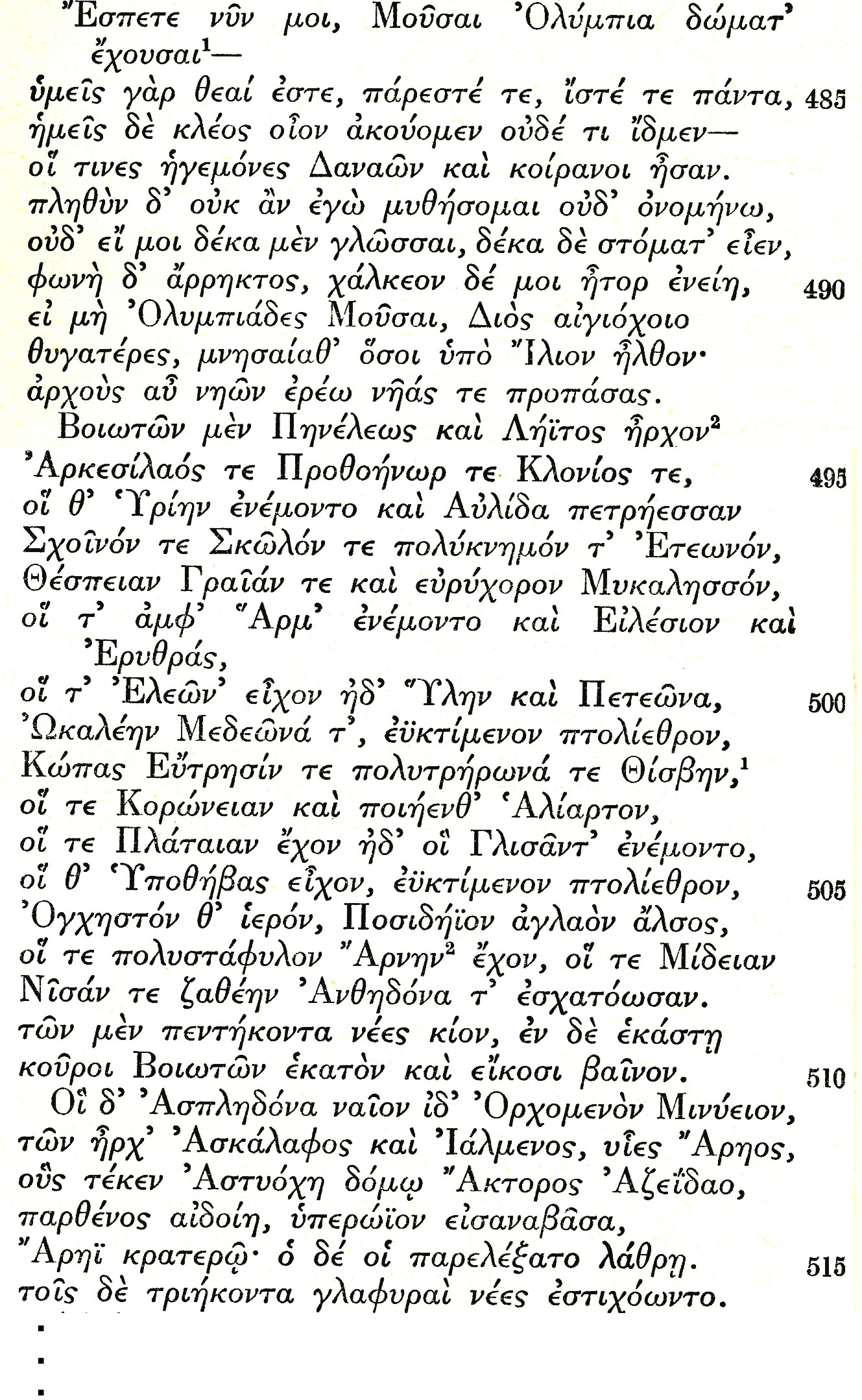

Below, in Greek and English, are the opening lines of Hesiod's cosmogony.

|

The beginnings of the Universebroad bosomed Gaia (Earth), a dwelling-place always secure for all [of the immortals, who inhabit the peak of snowiy Olympus,] and murky Tartarus in an inmost part of the wide-pathed earth, and Eros, who, most beautiful among the immortal gods, makes the limbs weak, and subdues the mind and wise counsel in the hearts of all gods and all men. From Chaos Erebus and black Night were born. But from Night were born Aether and Day, which Night bore after lying in love with Erebus. And Gaia first bore starry Ouranos (Heaven), equal to herself, so that he might cover her on all sides, and to be a dwelling place always secure for the immortal gods. And she bore the long Mountains, graceful dwellings of the goddess Nymphs, who inhabit the hilly valleys. And she gave birth to the harvestless Sea, without uniting in sweet love. But then, sleeping with Ouranos she gave birth to deep-eddying Ocean, Coeus and Crius and Hyperion and Iapetus and Theia and Rhea and Themis and Mnemosyne (Memory) and gold-crowned Phoebe and lovely Tethys. After these was born the youngest, wily Cronus, most terrible of her children; he hated his lusty father. |

Eros, archaic figure. Image from Roscher, Ausfürliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1884.

Quotation for March, 2017

For Women's History Month, a dedication to Artemis as goddess of childbirth, perhaps by Sappho |

Statue of Diana, the Roman Artemis. Located at the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California. Photo by C.A. Sowa. Small picture above: grave stele of Hegeso, 5th cent. B.C., detail.

Women poets of ancient Greece

As we conclude Women's History Month, we celebrate women poets of ancient Greece. Best known, of course, is Sappho of Lesbos. Enough of her work survives for us to appreciate her great talent. Her Hymn to Aphrodite survives intact, quoted entire by Dionysius of Halicarnassus. In another poem, her description of "falling apart" at the sight of a woman she loves, talking to a man — "He seems to me equal to the gods who sits across from you listening to your sweet speech..." — anticipates Patsy Cline's "I Fall to Pieces." The opening stanzas survive because Longinus quoted them as an example of the Sublime. We used this poem as the Quotation of the Month for February, 2008.

Sappho's sister poets

Sappho was not, however, alone. The work of her sister poets has almost entirely perished. Some are only names, but a few pieces survive. Corinna, choral poet from Tanagra in Boeotia, is traditionally said to have been a contemporary and sometimes rival of Pindar (c. 522 - c. 443 B.C.), although some scholars consider a later date. She composed the Contest between Helicon and Cithaeron, these being the two great mountains of Boeotia. (Cithaeron won, but Helicon retaliated by causing a disastrous landslide). Another woman poet, Myrtis, was said to be the teacher of both Corinna and Pindar. Hardly anything remains of the work of Praxilla of Sicyon (in the Peloponnese), a 5th century B.C. poetess, but she was sufficiently famous to be parodied by Aristophanes. Her "Hymn to Adonis" was laughed at because she makes Adonis say, when questioned in Hades about what he missed most in life, that the most beautiful things he left behind were the sun, the stars, and the moon — and cucumbers, apples and pears! Zenobius quoted the lines to explain the saying "sillier than Praxilla's Adonis," implying that produce is not on the stately level of the heavenly bodies. It seems, however, quite reasonable that a woman would realize that Adonis would miss the homely pleasures of a good meal. A pun has also been suggested on the word for "cucumbers" (sikuos) and the name of Praxilla's home town of Sikyon.

A dedication of thanks to Artemis for a successful childbirth

Our Quotation of the Month is perhaps by Sappho, or perhaps "in the style of Sappho" (hôs Sapphous, according to its heading). It comes from the Palatine Anthology, a collection of Greek poems and epigrams dating to the 10th century A.D. The selection is taken from an inscription on a statue dedicated to "Artemis Aethopia" by a grateful mother, following a successful childbirth. The words are those of the newborn girl, or perhaps of the stone itself, "wordless as I am," speaking through the inscription "laid out at my feet."

Artemis Aethopia, goddess of childbirth

Artemis is known as the virgin goddess of the hunt and of the wild mountains. The name is known from Mycenaean sources, but is of uncertain origin, perhaps pre-Greek. She is associated with cults of wild animals, especially the bear. The deer was also sacred to her. She became associated with various other goddesses and other functions. In mythology, she was known as the twin sister of Apollo, daughter of Zeus and Leto. The Romans identified her with Diana. She became identified with Selene, the moon, and Eileithyia, goddess of childbirth. She acquired the epithet Aithopia, from aitho "to burn," "to shine brightly," perhaps from her identification with the moon. (The word does not mean "Ethiopian," although that name comes from the same word, meaning "having dark (i.e. "sunburnt") faces.") It is as a goddess of childbirth that this statue and its inscription are dedicated to her.

The text we use is that of the Loeb edition of 1934 (ed. J.M. Edmonds) which has the child herself speaking, giving the first word of the inscription as pais "child." The manuscript itself has paides "children," meaning that the words are addressed to an audience of children, and that the stone itself is speaking. This reading is followed by other critics.

Below, in Greek and English, is one reading of the inscription.

|

"A thank-offering to Artemis Aithopia"setting down an unwearied voice at my feet: Aristo dedicated me to Artemis Aithopia, child of Leto, she herself being the daughter of Saunaïdas son of Hermocleitus. She is your attendant, O sovereign of women. Be gracious to her, and willingly bring glory to our family. |

Sappho about to jump off a cliff, as drawn by the anonymous former owner of my copy of the Greek Anthology.

Quotation for February, 2017

For Black History Month, Memnon, the Ethiopian hero of the Trojan War (Quintus of Smyrna, Posthomerica Book II) |

Memnon's departure for Troy, black-figure vase, ca. 550-525 B.C., Musées Royaux d'Art et d'Histoire, Brussels, Belgium. The Ethiopian hero prepares to aid the Trojans against the Greeks. (Image from Wikipedia.) The thumbnail drawing above shows a warrior wearing a linen cuirass, illustrating the word linothorex ("linen vest") in Autenrieth's Homeric Dictionary, 1876.

The Black Hero of the Trojan War

For February, in honor of Black History Month, we bring you the great Black hero of the Trojan War, Memnon, King of the Ethiopians. His mother was Eos, Goddess of the Dawn. The Ethiopians occupy a favored place in Homeric epic, where they are a semi-mythical people in whose company the gods enjoy lavish banquets. In Iliad 1.423-426, Zeus cannot help Thetis, mother of Achilles, because he is off visiting the Ethiopians. In Iliad 23.205-207, it is the goddess Iris who must hurry off to an Ethiopian sacrifice and banquet. In Odyssey 1.22-25, Poseidon receives sacrifices from the Ethiopians.

Memnon does not appear in the Iliad, which does not describe the last desperate period of the war, but ends with the funeral of Hector, slain by the raging Achilles in revenge for his killing of Patroclus. It is only after this that Memnon arrives with his army to support the Trojans. Memnon was, however, featured in other poems of the Epic Cycle, which were prequels and sequels that filled in stories of what happened before and after the war as told in the Iliad and Odyssey. All of these poems are lost, but summaries and excerpts survive in later authors. One poem was, in fact, called the Aithiopis, or the Ethiopian Poem, which narrates events that immediately follow the Iliad. It begins with the arrival of the Amazon Penthesilea, who comes to support the Trojans, but is killed by Achilles. Then Memnon arrives with his army, but he, too, is killed by Achilles. Achilles pursues the Trojans to the gates of Troy, where he is killed by Paris, who is also eventually killed.

The Egyptian singing statue

In Egypt, Memnon was identified with Amenhotep III (reigned ca. 1411-1375 B.C.). Two colossal statues of the pharaoh still stand near Thebes (as illustrated below). One of these gave a ringing tone when it was struck by the rising sun. While the reason may have been an accident of humidity, the sound was thought to be Memnon's greeting to his mother, Eos, or perhaps her greeting to her son.

Quintus Smyrnaeus' continuation of Homer

In the 4th century A.D., a poet known as Quintus of Smyrna undertook the writing of an epic poem called the Posthomerica, or "After Homer." In a fairly creditable imitation of the Homeric style, it provides another source for the contents of the lost Epic cycle, being based on plot elements of the sequels to the Iliad. Book I recounts the story of the Amazon Penthesilea, Book II tells the story of Memnon. Tall and black, he, like Achilles, wears armor made by the god Hephaestus.

Our Quotation of the Month describes Memnon's arrival in Troy, where the people, and especially old King Priam, are almost pathetically glad to see him, and think he will be their savior. Priam entertains him lavishly, and compares him to the gods. In the narrration that follows our excerpt, Memnon cautions Priam not to celebrate too much, and prefers to go to bed early, rather than stay up all night eating and drinking. His reservations turn out to be all too valid, as he will end up being killed. At the request of Eos, her son's body is wafted away by spirits, and his army is turned into a flock of birds, which fly away.

Below, in Greek and English, is the description of Priam welcoming Memnon.

Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica II.100-163

|

"A hero to help the Trojans"King Memnon with his blue-black Ethiopians, who came leading an immense army. Around them the Trojans, rejoicing all over the city, gazed at him, just as sailors, weakened after a destructive storm, behold through the upper air the radiance of the revolving constellation of the Great Bear. So the Trojan people rejoiced as they thronged about, but above all Priam, son of Laomedon. For in his heart he hoped very much to destroy the Greek ships with fire, helped by the Ethiopian men, since they had a huge king, and they themselves were many, all of them eager for war. Therefore, with great passion, he paid honor to the strong son of early-born Dawn, with fine gifts and sumptuous festivities. And they conversed with one another, over banqeting and eating, the one telling of the Danaan chiefs and the woes he had suffered, the other telling of his father and his mother Dawn's eternally immortal life, of the streams of the boundless goddess Tethys, of the sacred swells of deep-flowing Ocean, of the bounds of inexhaustible earth, of the place of the rising Sun, and of his entire journey from the Ocean to the city of Priam and the headlands of Mount Ida. He told how he cleaved asunder with his strong hands the divine army of the Solymoi, difficult to subdue, who barred his way, a deed that brought them unmanageable calamity and death So he told all those things, and how he had seen a myriad races of men; and Priam's heart rejoiced within him as he listened, and hanging on his words addressed him in an old man's words: "O Memnon, the gods have allowed me to look upon your army and upon you in our halls. Would that they might make it so that I could see all my foes destroyed upon your spears. You appear in every way like the invincible immortals, wondrously, like no one of the earthly heroes. Therefore, go hurl moaning slaughter against them. But now come delight your heart at my banquet, for today. But later go to battle, as befits you." |

Colossal statues of Amenhotep III in Egypt, identified as the famous "singing statues" of Memnon, King of Ethiopia, son of the Dawn goddess Eos. Changes in early morning humidity caused cracks in one of the sandstone statues to emit a singing sound at dawn. But you can no longer hear mother and son singing to each other. Later Roman repairs caused the singing to cease. (Illustration in W.H. Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1894-1897.)

Quotation for January, 2017

For the Chinese Year of the Rooster, Socrates' Rooster Offering to Asclepius (Plato, Phaedo) |

Asclepius, god of healing, accompanied by a snake, his usual animal symbol. Paris, Louvre. Illustration from Seyffert, Dictionary of Classical Antiquities 1899.

The Year of the Rooster

This is the Year of the Rooster! And not just any rooster. In the Chinese Lunar calendar, there are five kinds of rooster: Wood, Fire, Earth, Gold, and Water. The year 2017, whose New Year is celebrated this January, is a Year of the Fire Rooster. Roosters are talkative and sociable, but they can be vain and boastful. The Fire Rooster, however, is trustworthy, with a strong sense of timekeeping and responsibility. The U.S. Postal Service has issued a Lunar New Year's stamp with a picture of a rooster, as seen above.

"A cock for Asclepius"

The most famous rooster in antiquity is the cock which Socrates, in his last words, told Crito he owed to the god Asclepius. The story is told by Plato at the conclusion of the Phaedo. That dialog purports to recount the last day in the life of the great Athenian philosopher, as narrated by Socrates' disciple Phaedo to his friend Echecrates. In the political upheavals following the Peloponnesian War, Socrates (469(?)-399 B.C.), a philosophical gadfly, was sentenced to die by drinking poison hemlock for "corrupting the Athenian youth" and for "impiety."

In the Phaedo, Socrates' friends gather in his jail cell for one last conversation. The ensuing dialog concerns the nature of the soul, and whether it survives the body. It covers questions of reincarnation and transmigration of formerly human souls into animals, and what happens to good and evil souls. (Souls contaminated by living in the bodies of the gluttonous and violent are reincarnated in the bodies of asses and other such beasts (Phaedo 81e), the unjust pass into the bodies of wolves and hawks (82a), those who have practiced moderation pass into ants and bees (82b)).

At last an attendant brings the poison cup, and Socrates asks permission to pour a customary libation, but the attendant says the poison is carefully measured out, and none can be spared. Socrates' friends start to cry, and Socrates reminds them to act in a dignified manner, and explains (misogynistically) that that is the reason he sent his wife and other women away, because of their emotional outbursts. Socrates drinks the poison, and as his limbs progressively go cold, he reminds Crito that "We owe a cock to Asclepius, pay the debt and do not neglect it" (118a). Crito asks for further information, but Socrates dies, leaving the enigma of what he meant.

What did Socrates mean?

People from Plato's time onward have scratched their heads over Socrates' intent. Offerings were customarily made to Asclepius, god of healing, after being cured of some illness. The animal most closely associated with Asclepius was the snake, but animals, including roosters, were customarily sacrificed to him. Some writers (including Nietzsche) have thought Socrates meant that life is a disease of which he was cured. Others think he meant that his disciples were cured by his teachings of their misguided thoughts. It is also possible that there is a mundane explanation, that he really did owe an offering to Asclepius for some previous cure. Colin Wells in "The Mystery of Socrates' Last Words" in Arion 16.2 (Fall, 2008) offers another very sensible interpretation. Socrates had wanted to pour a libation (perhaps ironically) from his cup of poison, as if it were wine on some special occasion. Prevented from doing so, he still felt that some appropriate offering should be made to the gods. Hemlock was, in fact, sometimes used as a medicine in small doses, and Plato refers to the poison as a pharmakon ("drug" or medicine), so what god is more appropriate than Asclepius?

We also note that a rooster was a traditional gift exchanged by gay men; see the vase painting below.

Below, in Greek and English, are the final lines of the Phaedo.

Plato, Phaedo 117e-118a

|

"Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius"Then the man who gave the poison laid his hands on him, and, and after a little time examined his feet and legs, and pressing hard on his foot asked him if he could feel it. He said no. Then after that his legs. And going upwards thus he showed how he was becoming cold and stiff. And again he felt him and said that when the poison reaches the heart, then he will be gone. The area around his groin was already becoming cold, and uncovering himself — for he had covered himself — he said — and these were his last words — "O Crito, he said, we owe a cock to Asclepius; pay the debt and do not neglect it." "It shall be," said Crito. "but see if you say something else." To this question there was no answer, but after a little while he moved and the man uncovered him, and his eyes were fixed. When Crito saw this, he closed his mouth and eyes. That, Echecrates, was how the end of our companion happened, a man, as we may say, of all men of his time whom we have known, the best and above all the wisest and most just. |

Ganymede, boy favorite of Zeus, playing with a hoop and holding a rooster. Berlin painter, Louvre. The rooster was frequently exchanged as a gift by gay men. The other side of the vase depicts Zeus in pursuit of Ganymede. (Image from Wikipedia, photo by Bibi Saint-Pol.)

<---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2016 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: