These are quotations for the year 2020. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

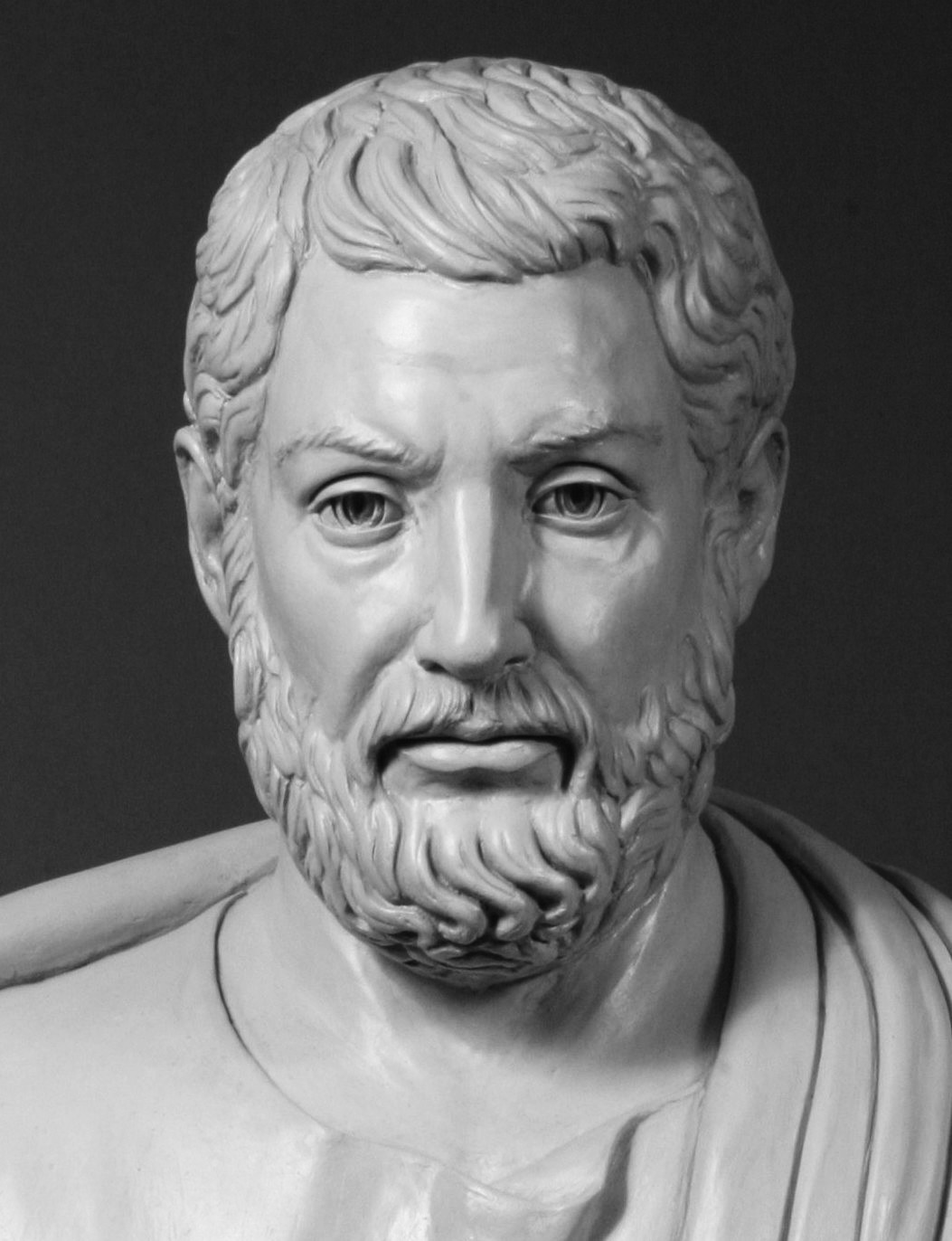

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2020, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2020 |

Below are quotations for the year 2020. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

- For 2020, see below.

- 2019

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

- 2015

- 2014

- 2013

- 2012

- 2011

- 2010

- 2009

- 2008

- 2007

- 2006

- 2005

- 2004

Quotations of the Month for the year 2020

Click on a link to read each quotation

2020

- December, 2020: For the Winter Holidays: The Conjunction of the Planets: Was it the Christmas Star?

- November, 2020: For Thanksgiving: Horace's Poem of Gratitude for a Friend's Return (Odes 2,7).

- October, 2020: For the Election Season: Political Polarization in Ancient Rome, Horace Epodes VII.

- September, 2020: The Last Crickets of Autumn: A Mediaeval Poem About Animal Sounds.

- August, 2020: For Women Winning the Right to Vote: Women in Ancient Greece.

- July, 2020: For the Americans With Disabilities Act: Hephaestus, the Lame God of the Forge.

- June, 2020: For Juneteenth: Friendly relations between gods and Ethiopians.

- May, 2020: For Memorial Day: People, not stone and timber walls, make a city strong (Alcaeus, fragment 29).

- April, 2020: For Earth Day: A Hymn to Gaia and an Epigram on her Moods.

- March, 2020: Precedents for the Coronavirus: The Plague at Athens, 430 B.C.: Thucydides Book II.

- February, 2020: Impeachment and Ancient Athenian "Ostracism:" Plutarch Life of Aristides.

- January, 2020: For the Lunar Year of the Rat: The Pseudo-Homeric Battle of the Frogs and Mice.

Quotation for December, 2020

For the Winter Holidays: The Conjunction of the Planets: Was it the Christmas Star? |

Above: "A Adoração dos Magos" ("The Adoration of the Magi"), by Domingos Sequeira, 1828, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon, Portugal. The Star of Bethlehem appears as a glowing light above mother and child.

A light in the darkness

It's all about light. At this time of year, there are a number of celebrations, religious and secular: Christians celebrate Christmas, Jews celebrate Hanukkah, and African-Americans celebrate Kwanzaa. New Year's Day marks the beginning of a new and hopeful year. All use an imagery of light: a star, candles, fireworks, and the many light displays that decorate our houses. And all come around the time of the winter solstice, when, in the Northern Hemisphere, the sun, which has gradually absented itself, begins to return. Although two months of sometimes brutal weather awaits, the event brings a message of hope for better things to come.

In the year 2020, there was an additional show of light in the sky. There was a rare conjunction of the planets Jupiter and Saturn, when the two planets appeared so close that, for those lucky enough to witness the phenomenon, they seemed to merge into one brilliant heavenly body. (Unfortunately, the skies in the Northeast were covered in clouds during this event.) Was such a conjunction the fabled Star of Bethlehem, which led the Wise Men to the infant Jesus?

The Bible story of the Three Wise Men

The story of the Star of Bethlehem occurs in only one place in the Gospels, in Matthew 2.1-12. According to the Gospel, in the reign of Herod the Great, puppet king of Judea under the Romans, "wise men from the East" (magoi apo anatolôn) arrived in Jerusalem to inquire concerning the whereabouts of the newly-born King of the Jews, "for they had seen his star." Herod, fearing a threat to his power, and learning from his experts that the child was in Bethlehem, sent the Wise Men to that town to bring him information. Herod (falsely) claimed that he too wished to worship the child.

The Wise Men follow the Star, which also arriving from the east, comes to a stop right over the house where Jesus lies with his mother Mary. They fall down and worship him, giving him gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Warned by God, they do not return to Herod, but go home another way. Joseph, also warned by an angel that Herod is up to no good, takes mother and child to Egypt. Herod, angry at being tricked, slaughters all the children two years and under in Bethlehem and the surrounding area (the Massacre of the Innocents, whose factual basis is questioned by historians).

The Gospel does not say how many Wise Men there were. Later writers, especially in Western Christianity, fixed their number at three, perhaps influenced by the three gifts which they gave to the Child. (Eastern Christians often fix the number as twelve).

Hanukkah

Hanukkah, the Festival of Lights, commemorates the Jewish Maccabean revolt against the Seleucid Empire, and the rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in the 2nd Century B.C. The event is described in the books of the First and Second Maccabees. The miracle of the one-day supply of oil lasting eight days is first described in the Talmud.

The Seleucid Empire was founded by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander the Great's generals, after the death of Alexander in 323 B.C. and the subsequent breakup of Alexander's empire. His empire eventually encompassed most of Alexander's Asian territories. By the Second Century, the empire of the Seleucids was coming apart, and by 143 B.C., the Jews, led by the rebel Judas Maccabeus and his four brothers, had achieved independence for Judea and the restoration of traditional Jewish religion, which had been banned by the Seleucid king Antiochus.

According to the rabbinic tradition of the Talmud, when the Jews reentered the temple, they found only one small jug of olive oil whose seal was unbroken, protecting it from contamination. It held only enough oil to light the seven-branched lamp, the menorah, for one day. But by a miracle, the oil lasted for eight days, burning brightly until more oil could be procured. It is this light in the darkness that is celebrated at Hanukkah, when one candle of the menorah is lighted each day for eight days, until all are lighted. Unlike the seven-branched menorah of the Temple, the Hanukkah menorah has nine branches; the ninth branch is lighted first, and the others are lighted from it. In 2020, Hanukkah began the evening of December 10 and ended the evening of December 18.

A reconstruction of the Menorah of the Temple created by the Temple Institute.

Kwanzaa

Kwanzaa is an African-American celebration held from December 1 to January 1. It was created in 1966 by Maulana Karenga, but is based on traditional harvest festivals from West and Southeastern Africa. Since these lands lie in the Southern Hemisphere, the Solstice they celebrate is the Summer Solstice, heralding not the cold of winter but the warmth of summer. As interpreted in Kwanzaa, the festival celebrates African heritage, unity, and culture.

Each day of Kwanzaa is dedicated to one of the Seven Principles: Umoja (Unity), Kujichagulia (Self-Determination), Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility), Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics), Nia (Purpose), Kuumba (Creativity), and Imani (Faith).

Among the symbols displayed at Kwanzaa is the kinara, a seven-branched candle holder, similar to the Jewish menorah. A black candle is placed in the middle branch, with three red candles to its left and three green candles to its right. The black candle is lighted first, and the others, in order from left to right, are lighted from it on subsequent nights.

Kwanzaa candles.

The conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 2020; Was it the Christmas Star?

On December 21, 2020, there was a celestial symbol of light, as the two planets Jupiter and Saturn seemed to overlap, making one super-bright light in the sky on the very night of the Winter Solstice. The planets are, of course, actually hundreds of millions of miles apart, and their closeness is an optical illusion. Such occurrences are rare, these particular planets have not been seen this close for 400 years. But there were several such conjunctions around the traditional date of the birth of Jesus Christ. A photo of the two planets as they appeared just before closing on each other in 2020 appears below.

There has been much speculation about the real facts behind the Biblical story of the Christmas Star. There is no reason to doubt that there was some such phenomenon around the time of the birth of Jesus, but both its nature and its date are matters of speculation. Some have suggested that it was a nova or perhaps a comet, but the conjunction of two or more planets would seem to fit the description of this event that has become so much a part of the Christian tradition.

We do not actually know the exact date of the birth of Jesus, except that he seems to have been born some time in the first century B.C. It happens that there were several conjunctions of two or more planets during this time period. Jupiter and Saturn appeared close to each other three times in 7 B.C. Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn passed in near-conjunction in 6 B.C. Venus and Jupiter appeared in close conjunction in 3 B.C. and again in 2 B.C. It seems likely that visitors come to gaze on the child they considered their Holy King did see something up there in the sky, seeming to be a beacon lighting their way. So maybe we were actually visited by the Christmas Star.

Quotation of the Month

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Greek and English, the story of the Chirstmas Star in the Gospel of Matthew. The Greek text is from an edition containing both the Greek and the Latin Vulgate, published by the Catholic Book Agency, 1955. The English is the King James translation, as published by the Massachusetts Bible Society, 1964.

New Testament, Matthew 2.1-12

|

The Wise Men inquire at Jerusalem, then follow the Star to Bethlehem

|

Saturn, top, and Jupiter, below, are seen after sunset from Shenandoah National Park, Sunday, Dec. 13, 2020, in Luray, Virginia. (Photo from the NASA web site.)

Quotation for November, 2020

For Thanksgiving: Horace's Poem of Gratitude for a Friend's Return |

Above: Roman Banquet, by Albert Baur, 1888.

Feelings of gratitude

In this season of Thanksgiving, we pause to think of those things for which we are grateful. Right now, that might seem difficult, but we can find reasons of many kinds, big and small, for which we can give thanks. Perhaps we are lucky enough to have loved ones, relatives and friends, neighbors or faithful pets. We may have good health or be surviving a bout of ill health. We may feel grateful for the gift of food or clothing from a stranger, or just a friendly look. Or we may rediscover a keepsake from a long-ago vacation. Those whose religion keeps them strong may feel grateful for the existence of God, or we may give thanks for the beauty of a golden maple leaf.

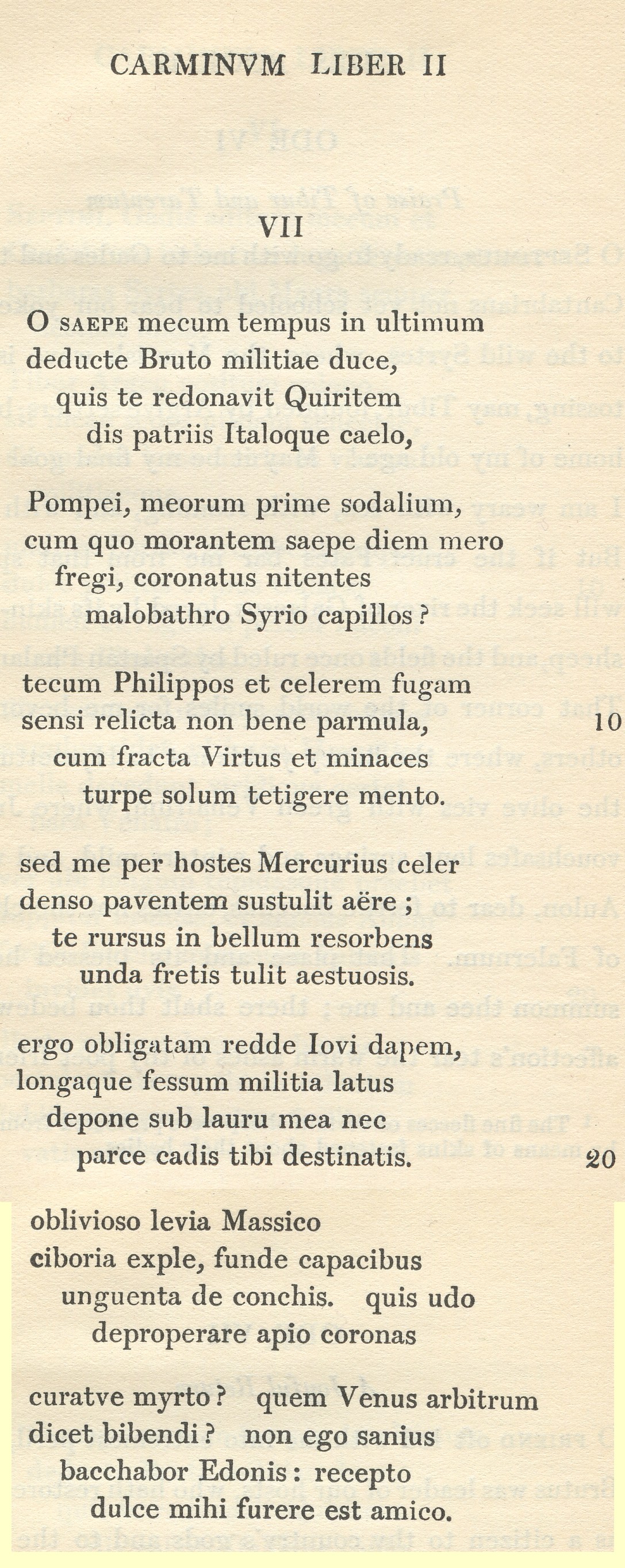

This month's Quotation of the Month is a poem by the Roman poet Horace in which he expresses gratitude for the return of an old friend and comrade, a fellow-veteran of the civil wars that followed the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C.

Horace escapes the fog of war

This month's poem is a follow-on to last month's selection (Quotation for October, 2020), Horace's Epode VII. Written probably around 38 B.C., it bemoans the fighting that took place between the partisans of the assassins Brutus and Cassius, who fought for the old Republic and the partisans of the new Second Triumvirate, Octavian (Julius Caesar's heir and adopted son), Mark Antony, and Lepidus. By 42 B.C., after the Second Battle of Philippi in Macedonia, Brutus and Cassius were dead, but the Triumvirs fell to fighting each other. Octavian (later Augustus Caesar) finally defeated Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium in 21 B.C.

Horace participated in the battle at Philippi on the Republican side. Horace was of humble origin (his father seems to have been an enslaved captive during part of his life, but was successful enough to provide his son with a good education). Yet Horace was given the position of tribunus militum of a legion, a promotion that caused jealousy among his well-born fellow soldiers. His identification with the cause may have been thin, as he reports that he ran away, "throwing away his little shield," a shameless plagiarism from the Greek poet Archilochus (7th cent. B.C.), who tells the same tale about himself. (The poets Alcaeus and Anacreon also repeated the same story about themselves.)

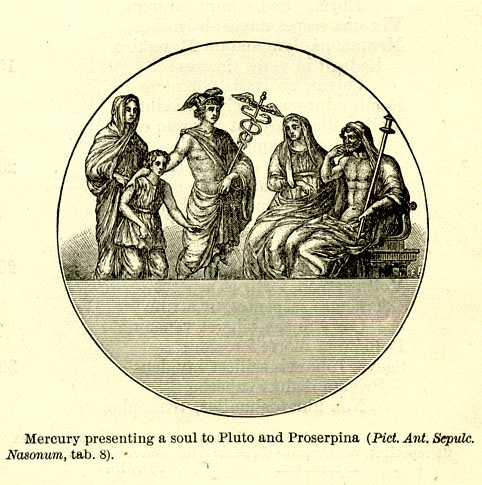

Horace also borrows a familiar device from epic, claiming to have been rescued from battle by the divine guide Mercury, who spirited him away in a cloud of invisibility.

Amnesty and reconciliation, reunion with a friend

Horace quickly made up with the party of the new leader, Octavian, by making friends with the wealthy Maecenas, Octavian's right-hand man. Horace, as well as Vergil, became the new Emperor's propagandists.

His friend Pompeius (about whom nothing is known aside from this poem) was not so lucky. He was drawn back into the war "by a wave of stormy waters" and continued to serve on the losing side.

In 29 B.C., Octavian offered amnesty to those who had fought against him, and allowed them to return to Italy. Horace's Ode 2.7 seems to date from this time. Horace remembers the good times he shared with his friend, killing time on long, monotonous days by drinking wine. He does not name Octavian, only alluding to his benefactor by saying "Who was it that returned you to Italy and your ancestral gods as a Roman citizen (Quiritem)?" He suggests that a feast is owed to Jove, especially since he has been saving special jars of wine for his friend. He looks forward to having a crazy time (furere) with his old comrade.

Below, in Latin and English, is Horace's Odes Book 2 No. 7. The text is that of the Loeb edition of 1914. The phrase "Who will Venus appoint ...," which I have expanded to "Who will the Venus of dice appoint ..." is a reference to the "Venus throw," the highest throw of the dice, where the numbers that appear are all different. A throw of the dice determined who should be leader of the drinking, and hence of the feast.

Horace Odes 2.7

|

My friend has returned, let us give thanks and rejoice

O you who were often led with me into extremest peril, |

Mercury, the guide and herald of the gods. The illustration depicts Mercury (Hermes) in his role as psychopompos, or conductor of the souls of the dead into the Underworld. In his Ode, Horace claims that Mercury saved his life by taking him up in a cloud of invisibility.

Quotation for October, 2020

For the 2020 Election Season: Political Polarization in Ancient Rome, Criticized by Horace |

Above: Horace (on the right) with Maecenas (center) and Augustus (seated, on the left). From a wall painting found in the palace of Augustus on the Palatine.

The political leaders are all fighting each other

The word most often used to describe the current political situation in the U.S. is "polarization." Each of the two principal candidates for President and their supporters try to convince voters that the other will bring about the ruin of democracy in America. Less time is spent explaining how the policies of each will benefit Americans than on how the other person will bring about chaos and civil war.

The two candidates do not have actual armies backing them up, but some of the more extreme partisans on both sides have indulged in violence or threats (some quite credible) of criminal behavior.

Each candidate accuses the other of accepting help from foreign governments.

Will nothing bring us together?

Julius Caesar's successors fight for dominance

The late first century B.C. in Rome was also a time of great civic unrest, with political leaders fighting each other for dominance. In 44 B.C., Julius Caesar, who had centralized power in his own hands by being made Dictator for Life, was assassinated by Brutus and Cassius. In 43 B.C., after much political turmoil, the Second Triumvirate was formed, consisting of Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian, Julius Caesar's great-nephew, posthumously adopted in his will as his son. Feelings about the assassination were complicated by the fact that Caesar had been very popular among the Roman middle and lower classes, as opposed to the aristocratic senators attempting to restore what they saw as the legitimate Republic.

Brutus and Cassius were defeated by the triumvirs at the Second Battle of Philippi in 42 B.C. However, the three leaders quickly fell to fighting each other. As rulers of their separate Roman provinces, they really did have armies of legionaries backing them up. There was also foreign interference. Mark Antony had his infamous affair with the Egyptian queen Cleopatra (who had also had an affair, and a son, with Julius Caesar) and formed a military alliance with her. Antony and Cleopatra were defeated by the forces of Octavian at the naval battle of Actium in 31 B.C. (Lepidus, the other member of the triumvirate, had already been sidelined). Octavian, immensely popular with the Roman legions, took sole control.

In 27 B.C., Octavian was given the title "Augustus" by the Roman Senate, and it is as Augustus Caesar that he is generally known. And thus the Roman Republic, though retaining the shell of its institutions, became the Roman Empire.

Horace Epode VII: a plea for civil peace

In 38 B.C. or thereabouts, the poet Horace, in a spirit of pessimism, composed his Seventh Epode. He laments the fact that peace, which seemed to have come to Rome, had evaporated, and political leaders were again renewing hostilities. Warfare, which should have been turned against Rome's enemies, was turned on each other. The poem ends pessimistically, with the conclusion that the ancient curse of Romulus' killing of his brother Remus, was continuing down to successive generations.

Horace, who participated on the Republican side at Philippi, would become reconciled in time to the new regime. He was introduced to Augustus' wealthy political strategist Maecenas, who became the patron of both Vergil and Horace, and both poets, through their poetry, became spokesmen for the new Emperor.

Below, in Latin and English, is Horace's Epode VII. The text is that of the Loeb edition of 1914.

Horace Epode VII

|

Romans, why are you again making war on each other?

Whither, whither, are you rushing to ruin, scoundrels? Why |

Above: Triumphal Arch of the Emperor Augustus, Rimini. Photo by Tobabi1, via Wikipedia.

Quotation for September, 2020

The Last Crickets of Autumn: A Mediaeval Poem About Animal Sounds |

Above: Illustration from A.W. Kappel and W. Egmont Kirby, Beetles, Butterflies, Moths, and Other Insects, 1893, Plate XI. The field cricket (Gryllus campestris) is No.8. Other well-known insects are No. 6 (cockroach) and No. 9 (Great Green Grasshopper).Top: Common Nightingale, Luscinia megarhynchos, photographed in Istria-Novigrad, 1998, by Orchi.

The fall crickets are still singing in the fields

It is autumn, and the days are getting chillier, but some days the temperature rises, and we almost think that summer has returned. At night, the crickets are still singing, quickly when the weather is warm, slowing down as the temperature drops. The male cricket sings a variety of songs: to announce his identity, to attract a female, or to engage in combat with a competitor. Sometimes they seem to call antiphonally, with a cricket on one side of the garden answering one on the other.

There is more than one kind of buzzing, chirping insect, and each has its own noise-making equipment, activated by wiggling various parts of wings, abdominal ridges, etc. The Fall Field Cricket (Gryllus Pennsylvanicus) makes its characteristic chirping sound by rubbing its wings together. One wing has a sort of scraper, which it rubs across a file of evenly spaced teeth on the other wing. The wings are not used for flight, however. It escapes its predators (such as a human hand trying to catch one) by leaping out of the way on its powerful hind legs.

Albus Ovidius Iuventinus' "Elegia de Philomela": All about animal sounds

Our Quotation of the Month is from a poem called Elegia de Philomela, "An elegy About the Nightingale," ascribed to Albus Ovidius Iuventinus, whose identity is cloaked in mystery. Its earliest appearance is in a manuscript of the eleventh century A.D, and some speculate that the author was a German monk, but the poem may go back further than that. It is a catalog of animal sounds, describing the voices of a menagerie of birds, snakes, and other animals. Earlier Roman writers, including Suetonius and Varro, also collected onomatopoetic or mimetic Latin words imitating the sounds of various beasts. Our poem may have its origins in these.

The poem is called an "elegy" not for its mood but because it is written in the metrical form called "elegiac," with alternating long and short lines. Its full title is Elegia de Philomela, et de aliarum avium, simul et quadrupedum, vocibus, "Elegy on the Nightingale, and on the Voices of Other Birds and Quadrupeds."

The poem begins with praises for the nightingale, whose varied song is capable of imitating the voices of many birds. Also. unlike birds who sing only at night or during the day, it can sing around the clock. The nightingale takes its name, "Philomela," from the story of Philomela, sister of Procne, who was raped by her brother-in-law Tereus. Their story was told in an earlier Quotation of the Month. Philomela was turned into a nightingale, who sings a song of her sorrow, Procne became a swallow, and Tereus turned into the hoopoe with its extravagant crown of golden feathers. (In real life, only the male nightingale sings, to attract a mate, but this makes a good story!)

The poem goes on with its catalog of animal sounds: The pig grunts (grunnit), the bull bellows (mugit), the owl (bubo) hoots (bubulat) as it brings ill luck to human kind. And so on for seventy lines.

Et grillus grillat: chirping crickets

Near the conclusion, which we show below, we come to the cricket, (grillus) who chirps (grillat). The shrew squeaks (desticat), and the snake slithers and hisses (serpendo sibilat). The frog goes "Coax!" (coaxat), an obvious reference to Aristophanes' Frogs, who go "Brekekekex! Coax! Coax!."

Finally our poet admits that no one can catalog all the beasts and their voices, but all are creatures of God.

Below, in Latin and English, are the concluding lines of "Iuventinus'" Elegy on the Nightingale. The text is that printed in Poetae Latini Minores Vol 6, edited by Io. Christianus Wernsdorf, 1799. This poem appears on pp. 388-401.

Elegia de Philomela vv. 62-70

|

Animals both vocal and silent: how to describe them all?. . . |

Above: "The Rape of Philomela by Tereus." Engraved by Johann Wilhelm Baur for a 1703 edition of Ovid's Metamorphoses Book 6, plate 59.

Quotation for August, 2020

For Women Winning the Right to Vote: Women in Ancient Greece |

Above: Running Girl, bronze, 520-500 B.C., British Museum. Spartan, found in Serbia. Photo by Caeciliusinhorto, via Wikimedia.Top: Artemis and deer. Bronze Medaillion of Antoninus Pius. Illustration from R.H. Roscher, Ausfürliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1894-1890.

100th annivesary of women's right to vote

In August, 2020, we celebrated the 100th anniversary of U.S. women winning the right to vote. The 19th Amendment was passed by Congress on June 4, 1919, and ratified on August 18, 1920. Some states had already granted women the vote, but the 19th Amendment made it federal law. The names of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton are well known, but less recognized is the important role played by African American women. Their role is exemplified by the activist and abolitionist Sojourner Truth and the journalist Ida B. Wells, who fought for rights for both Black and white women, as well as for civil rights for both Black men and women.

The true nature of democracy is still a matter of debate and conflict even today.

Women in ancient Greece

This month we look at women's rights in ancient Greece, often called, especially with regard to Athens, the "cradle of democracy," though here, too, the application of "democracy" was selective.

At Athens and in most Greek cities, women could not vote, hold public office, serve on juries, or own property. Detailed knowledge of life in Greek cities other than Athens is mainly dependent on the evidence of Athenian writers, and of necessity reflects the Athenian point of view.

Women in ancient Thebes

In 1995, Barbara Goff wrote an interesting article in the Classical Journal called "The Women of Thebes." Goff shows how Athenian dramatists positioned Thebes, the great city that was a rival of Athens, as a kind of "anti-polis," where society and social norms were the opposite of Athens, as a means of confirming Athens' own identity. Women such as Antigone and Iocasta are portrayed as being deprived of their "natural" role in rituals, such as caring for the dead, but are called upon to take a public role in solving disputes between warring male family members, who were derelict in their own prescribed roles.

We do not know if this reflects in any way the actual position of women in Thebes (or men, for that matter), or whether this is Athenian propaganda.

Goddesses, of course, were exempt from the limitations of human women. We cannot imagine Athena being subservient to a husband!

Women in ancient Sparta

Women in Sparta were the exception, having freedoms unheard of in other cities. They received education similar to that of men, participated in exercises and athletic events, and owned property in their own right, mostly by inheritance. They wore short tunics, slit up the side, attached over one shoulder, leaving the other shoulder and breast exposed, as seen in the famous "Running Girl" statuette shown at the top of this piece (much to the scandal of other Greeks). According to Aristotle, women owned forty percent of the land in Sparta.

But the relative freedom of Spartan women had a dark side. Sparta was a militaristic society, and women were expected to be strong and smart so that they could give birth to strong soldiers. Here, again, our knowledge comes almost entirely from non-Spartan sources. Important sources are the Constitution of the Lacedemonians (Lacedaemonion Politeia) by the Athenian soldier and historian Xenophon, Plutarch's Life of Lycurgus, and Aristotle's Politeia.

Sparta's rigid class structure

Sparta was an oligarchy, with a strict class structure. It was ruled by two kings, both supposedly descended from Heracles. The top class were the Spartiates, who were the smallest class, but were the only true citizens. Below them were the perioikoi ("living around") who were free non-citizens, and the helots, descended from conquered Messenians and others who were enslaved, but were more in the nature of state owned serfs. Spartiate boys were sent to military school at the age of seven, and even as adults, spent most of their time in military service, leaving the administration of the household to their wives. Women did not marry until their twenties, to ensure that they would be healthy mothers of healthy men. Babies were judged at birth, and if they were not healthy, it is reported that they were killed. If the husband was not able to have children, the wife could have children by another man. Women did not have to concern themselves with typical women's work like weaving, because these tasks were done by slaves. Hence the opportunity to engage in athletics and other activities.

Tyrtaeus and Alcman, Spartan poets

We have fragmentary writings by two Spartan poets, Tyrtaeus and Alcman. Tyrtaeus wrote elegaic poetry in the mid-seventh cent. B.C. Most of what survives consists of sometimes lengthy quotes in other authors. His poetry, popular with the army, glorified warfare and dying for one's country.

Alcman shows us another side of Spartan society. Alcman, a lyric poet, probably lived in the late seventh cent. B.C. We know of six books of his choral lyric poetry, but these have, unfortunately been lost since early Mediaeval times. In 1855, a papyrus fragment was found in a tomb near Saqqara in Egypt, containing about 100 verses of a partheneion, or Maidens' Song, apparently intended to be sung at a festival. Since then other fragments have been found in garbage dump at Oxyrhynchus.

Alcman's maiden song

The Partheneion, composed in the Doric dialect, was to be performed by competing choruses of young women, apparently at a festival of the goddess Artemis Orthia, the remains of whose temple can still be seen outside of Sparta. (See the illustration below. The reading "Orthia" in the damaged papyrus may or may not be correct.) The fragment of the Partheneion that survives, although composed by a man, shows us perhaps a little of how the women of Sparta saw themselves. The two choruses are led by their choregoi or chorus leader, Agido and Hagesichora (whose name literally means "Leader of the Chorus"). The unnamed narrator, a member of Hagesichora's band, expresses her admiration for the beauty of her leader, as well as that of the other girls. She compares the girls to spirited horses, racing against each other. The comparison to racehorses emphasizes the women's athleticism. There is possibly also a homoerotic theme here, reminiscent of the poetry of Sappho of Lesbos, a near contemporary.

Our Quotation of the Month is an extract from Alcman's Partheneion, given below in Greek and English. Hagesichora is compared to an "Enetian racehorse." The Eneti were a people who inhabited a region of Paphlagonia, on the southern coast of the Black Sea, at the time of the Trojan War. The area was known for its population of wild mules (as described in Homer's Iliad). The narrator contrasts the high-spirited horse with "the offspring of wild asses." Later, the two chorus leaders, Hagesichora and Agido, are compared to two other breeds of horses, the Kolaxian and Ibenian. The women are also compared to doves, if that reading is correct.

Alcman First Partheneion vv. 39-63

|

The young women sing of their mutual admiration

. . . As for me, I sing |

The remains of the temple of Artemis Orthia in Sparta, May 15, 2019. Via Wikipedia.

Quotation for July, 2020

For the Americans With Disabilities Act: Hephaestus, the Lame God of the Forge |

Above: Hephaestus at his forge. From From R.H. Roscher, Ausfürliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1894-1890.Top: The symbols of Hephaestus: the forge, hammer, and tongs.

Thirty year anniversary of the Americans With Disabilities Act (1990)

The Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA, was first introduced in the House and Senate in 1988, and was passed in in its final version in 1990. It was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush on July 26, 1990. It forbade discrimination in employment and in public accommodiations on the basis of race, religion, sex, or national origin. A number of disabilities were covered, including physical disabilities such as cancer, diabetes, or missing limbs or use of a wheelchair, and intellectual challenges such as autism or schizophrenia. Amemdments extending the scope of the law were signed by President George W. Bush on September 25, 2008.

Gender identity or orientation are not covered, since homosexuality is no longer defined as a mental disorder, but the Supreme Court rendered a decision on June, 2020, that they are covered by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, since the bar to discrimination on the basis of sex also covers sexual orientation!

Hephaestus, the lame blacksmith god

Perhaps the most famous personage with a disability in Greek epic is Hephaestus, the lame blacksmith and metal worker of the gods. Myths differ as to his birth and the source of his disability. In some versions, he is the son of Zeus and Hera. But in the earliest accounts, Hesiod's Theogony and the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, Hera bore him by herself, in revenge for Zeus' giving birth to Athena without her. But his foot was shriveled, and Hera threw him out of Heaven. He was then cared for by the sea-goddess Thetis. (A later account attributes his lameness to a different incident, in which he was thrown out of Heaven by Zeus when Hephaestus defended his mother from an attack by Zeus.)

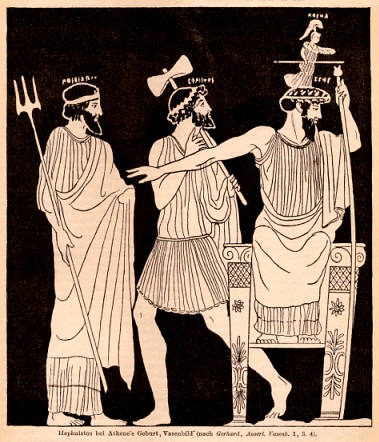

Vase paintings turn the story of Hephaestus' birth on its head, so to speak, having the smith god, already grown up, wielding an axe at Zeus' head to allow Athena to be born from his skull (see below).

Athena's birth from the head of Zeus, with Hephaestus standing by holding an axe. Illustration from R.H. Roscher, Ausfürliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1894-1890.

Thetis asks Hephaestus to make armor for her son, Achilles

We think of Hephaestus as the "blacksmith god," (see the illustration at the top of this essay), but he was much more than this. He was a skilled worker and inventor in metal and materials of all kinds, especially when the result had miraculous qualities. He was said to have designed Hermes' winged helmet and sandals, the chariot of Helios, and even the manufactured woman Pandora, made out of clay, who infamously let the evils out of the jar. He built lifelike automatons of gold, his assistants in his workshop, and he made an amazing shield and armor for the hero Achilles.

The Iliad begins with the Greek hero Achilles withdrawing from the battle between the Greeks and the Trojans, because the Greek general Agamemnon, has taken from him the girl Briseis, his trophy of war. (Briseis herself is "unwillingly" led away from the hero.) When Achilles refuses to fight, his best friend Patroclus goes out to fight in his armor. Patroclus is killed by the Trojan hero Hector, and Achilles rejoins the battle, vowing revenge. He needs new armor, and his mother Thetis goes to Hephaestus in Book 18 (vv.369 ff.) to request that he make her son new armor. Hephaestus is happy to oblige, repaying her for her care for him when he was rejected by his mother, Hera. Much of the rest of Book 18 is taken up by the description of the fantastic shield of silver and gold that Hephaestus fashions, on which are depicted complete scenes of city and country, peace and war, herdsmen and fields, war and rural dances. This is rich fantasy, but an almost believable exaggeration of inlaid metalwork actually found in Mycenaean tombs (see the dagger shown below).

Dagger. Bronze, inlaid with silver and gold. Hunting lions. Mycenaean Late Bronze Age, 16 century BC. National Archaeological Museum of Athens N 394. (From Wikimedia, photo 23 March 2014, 13:17:46 by Zde.)

Hephaestus' golden robots

Hephaestus also built self-moving automatons, endowed with artificial intelligence. When Thetis enters, he is making self-driving goden tripods that will wheel themselves into the gods' banquet hall, then wheel themselves back when not needed. He also has made for himself golden handmaidens, endowed with intelligence and speech, to help him, since he is lame. Although he is physically disabled, he has invented the most wonderful workarounds, and has turned his inventiveness in most amazing directions!

Below, in Greek and English, is a portion of Thetis's visit to Hephaestus, and the description of his golden helpers (Iliad 18.410-427).

Iliad 18.410-427

|

Hephaestus rises, limping, from his forge, to greet Thetis

. . . He spoke, and rose from his anvil, huge and monstrous, |

Achilles sulking in his tent. Illustration from A Burlesque Translation of Homer, Fourth Edition, Improved, 1797, Vol. 1, p. 41.

Quotation for June, 2020

For Juneteenth: Friendly relations between gods and Ethiopians (Iliad 1.419-430 and 23.198-211) |

Above: Memnon, king of the Ethiopians, accompanied by two other Ethiopians. Black-figured amphora, ca. 510 B.C. from Vulci. Munich, Staatliche Antikensammlungen. Photo by Bibi Saint-Pol, via Wikimedia.Top: Janiform (i.e. with double face) aryballos, or flask. From Attica, ca. 520-510 B.C. Louvre, photo by Jastrow, via Wikimedia.

Juneteenth, the end of slavery in the U.S.

June 19, or Juneteenth, is considered as marking the end of slavery in the U.S. Long celebrated by African Americans, it is now being recognized officially as an American holiday. Specifically, it celebrates the day, June 19, 1865, on which the people of Galveston, Texas, and by extension, all of Texas, learned that the slaves were free. The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863 had already freed all the slaves in the states that had seceded, but news traveled slowly in the nineteenth century, and Galveston, except for a brief period in 1862, was under Confederate control for the entire war. On April 9, 1865, the war officially ended with Lee's surrender, and news did not reach Texas for more than a month. In fact, fighting continued into May on the banks of the Rio Grande.

On Monday, June 19, 1865, Union Major General Gordon Granger and 2000 Federal troops arrived in Galveston to take possession. Marching to several locations, beginning at the Army headquarters and ending at the Negro Church on Broadway (since renamed Reedy Chapel-AME Church) he read out General Order No. 3, which proclaimed that

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

Traditionally associated with the reading of the Proclamation is the Galveston mansion known as Ashton Villa, a historic home built in 1859 from whose balcony Gen. Granger is often said to have delivered the order. It still stands, and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Ethiopians among the Greeks and Romans

The ancient Greeks and Romans were very aware of black Africans, both in real life and as a half-mythical fantastical people. "Ethiopia," a geographic name of somewhat vague reference, referring generally to a world of dark-skinned people, extending from India to sub-Saharan Africa, took on a romantic image. ("Aithiops" means "burnt-face" in Greek.)

In Rome, the African-Roman playwright Terence (Publius Terentius Afer — "the African") left us some of the finest Roman plays that have survived. Vergil, in his homoerotic second Eclogue, praises the beautiful black boy, believing him more beautiful than his white rival:

O beautiful boy, do not trust too much in your complexion:

white privet flowers fall, but black blueberries are gathered.

Ethiopians in epic poetry

In epic, which often turns out to have a strong basis in historic fact (although embroidered by myth), we encounter many black characters. Memnon, king of the Ethiopians, had an entire epic, the Aithiopis, devoted to his exploits, dating from the time of Homer. Said to be the son of the dawn goddess Eos and the the Trojan prince Tithonos, he joined his Ethiopian army with that of the the Trojans at Troy. He was slain by Achilles, but was made immortal by Zeus. In Egypt, he was identified with Amenhotep III (reigned ca. 1411-1375 B.C.), whose colossal statues near Thebes gave a ringing tone when they were struck by the rising sun, an event thought to be Memnon's greeting to his mother, Eos.

In Odyssey 19.244-248, Odysseus' herald Eurybates ("wide-stepping") is described thus (by Odysseus in disguise, to Penelope):

And there was a herald, a little older than he,

round in his shoulders, of black complexion, woolly-headed;

Eurybates was his name. Odysseus honored him above his other

companions, because his thoughts were in harmony with his.

The gods, including Zeus, enjoy banqueting with the Ethiopians

The Homeric gods were particularly fond of going to banquets given by the far-off Ethiopians. Apparently the Ethiopians gave good banquets, as well as sumptuous sacrifices that preceded the feasts. For example, in Odyssey 1.22-25,the god Poseidon is depicted as receiving sacrifices of bulls and rams from the Ethiopians:

But he [Poseidon] had gone to the far-off Ethiopians

— the Ethiopians are divided in two, the most distant of men;

some live where Hyperion sets, others where he rises.

There he receives hecatombs of bulls and rams,

and there he enjoys sitting at the feast. . .

A banquet with the Ethiopians could preempt any other duties, and our Quotations of the Month illustrate this principle:

Achilles asks for help from Thetis

In Iliad 1.423-426. Achilles, smarting at the taking of the girl Briseis from him by his commander, the Greek King Agamemnon, begs his mother, the sea-goddess Thetis, to ask Zeus to help the Trojans, to punish Agamemnon for his lack of respect for himself, "the best of the Achaeans." Thetis replies that she will ask Zeus's help, as soon as he returns, but that he is presently away from Olympus:

"for Zeus went yesterday to the Ocean, to the blameless Aethiopians,

for a banquet, and all the gods followed with him."

Patroclus' funeral pyre fails to ignite

In Iliad 23.205-207, the funeral pyre of Patroclus fails to burn, and Achilles prays to the North Wind and the West Wind to blow, to ignite the fire, promising them fine offerings. The messenger goddess Iris goes to the Winds to ask them to blow. She finds all the winds at the home of the West Wind, Zephyros, enjoying a feast, which they invite her to join. But she, having delivered her message, declines because of a prior engagement, saying,

"I can't sit down, for I am going back to the streams of Ocean,

to the land of the Aethiopians, where they are sacrificing hecatombs

to the immortals, that I may share in the sacrificial banquet."

After Iris departs, the winds rise up "with a wonderful din" and fall upon the land of Troy, igniting the fire.

Below, in Greek and English, are Thetis' apologies to her unhappy son, Achilles, and Iris expressing her regrets to the winds' banquet.

Iliad 1.419-430

Iliad 23.198-211

|

Zeus is away visiting the EthiopiansTo speak your words to Zeus who delights in the thunderboltI will go myself to snowy Olympus, in hopes of persuading him. But you, remaining by the swift-sailing ships, continue to rage against the Achaeans, and refrain entirely from battle. For Zeus went yesterday to the Ocean, to the blameless Aethiopians, for a banquet, and all the gods followed with him. But on the twelfth day he will come back to Olympus, and then I will go to Zeus's house with the bronze threshold and, clasping his knees in prayer, I think that I can persuade him. So speaking, she departed, and left him there, angry in his heart because of the fair-girdled woman, whom they had taken from him against his will . . . Iris has nn invitation from the Ethiopians. . . Immediately, Irisheard his prayer and went as a messenger to the winds. They were all together at the house of the fierce-blowing West Wind feasting at a banquet. Running up, Iris stood on the stone threshold. As soon as their eyes saw her, they all leaped up, and each called her to himself. But she refused to sit, and spoke: "I can't sit down, for I am going back to the streams of Ocean, to the land of the Aethiopians, where they are sacrificing hecatombs to the immortals, that I may share in the sacrificial banquet. But Achilles prays that the North Wind and the noisy West Wind come, and he promises them fair offerings, that they may rouse the pyre to burn, on which lies Patroclus, for whom all the Achaeans lament." |

Ashton Villa, Galveston, Texas, traditionally associated with the reading of General Order No. 3, announcing that the slaves were free. From an antique postcard, ca. 1905 (collection of C.A. Sowa).

Quotation for May, 2020

For Memorial Day: People, not stone and timber walls, make a city strong (Alcaeus, fragment 29) |

Alcaeus and Sappho. Location: Munich, Staatliche Antikensammlungen. Photo by Bibi Saint-Pol, via Wikimedia.

The citizenry themselves are the best safeguard

On May 25, we celebrated Memorial Day, when we pay tribute to the men and women who have sacrificed their lives in the service and defense of their country. This day gives us the opportunity to reflect on what it means to defend and protect our nation.

There are those who think that the best defense is to literally build fortification walls of stone and cement and to withdraw from all contact with other nations and from all international agreements. This conduct is not only useless but can backfire. Whereas useful exchange, of commodities, people, and information is strangled, harmful exchange of corporeal items such as drugs, and incorporeal material such as malign computer programs, always find a way to cross borders. And as we have seen with the pandemic of coronavirus, a virus knows no borders. Walls do not help in a plague: we saw in the Quotation of the Month for March that the Great Plague at Athens of 430 B.C. was exacerbated by the close penning up of thousands of inhabitants behind their Long Walls — with no social distancing!

The fundamental way to achieve national strength is to develop a strong people who not only have a robust set of ideals but who live up to those ideals, and who set an example to be followed by other nations.

Our Quotation of the Month is a short fragment from the Greek poet Alcaeus of Mytilene, from the sixth century B.C., expressing a sentiment that is surprisingly appropriate, that the strength of a city-state is not in its walls but in its people.

Alcaeus, the other poet from Lesbos

Alcaeus (ca.620-ca.580 B.C.) was from the city of Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. When we think of Lesbos, we generally think of the poetess Sappho (ca.630-ca.570 B.C.), and in fact the two very likely knew each other. (Legend has them be lovers, but there is little if any evidence for this.) Alcaeus belonged to the aristocratic ruling class of Mytilene, and was involved in its political disputes and rivalries. Little is known of Sappho's family. Their poetic output differed in scope, hers being of a more personal nature, whereas he composed poetry on a variety of subjects, including hymns to various gods, war songs, love songs, drinking songs, and political commentary. Both wrote in their native Aeolic dialect.

But both Alcaeus and Sappho suffer from the loss of most of their poetry. It exists today mainly in quotations in other writers and in fragmentary papyri found in the ancient rubbish dump at Oxyrhynchus and elsewhere in Egypt.

Alcaeus on defense of the city

The quotation we have chosen is the one labeled as No 29 in the Loeb edition. It was quoted by Aristides in The Four Great Athenians (and paraphrased by other writers). The city, Alcaeus says, is composed not of stone and timber, but of men.

Below, in Greek and English, are the words of Alcaeus on what makes a great city.

Alcaeus Fragment 29

|

The people themselves are the wallsNot stones and timber, not the craftof the builder are the city, but wherever there are men who understand how to keep themselves safe — there are the walls and the city. |

An ancient hero. Sculpture of Heracles capturing the Deer of Ceryneia (his third labor). Location: the Museum at Delphi. (From a postcard.)

Quotation for April, 2020

For Earth Day: A Hymn to Gaia and an Epigram on her Moods |

A view from my back window. The magnolia tree in the back yard, with birdbath in the foreground. Photo by C.A. Sowa.

A look out the window at Nature

On Earth Day (April 22), many were stuck this year inside a house or apartment having to enjoy nature by just looking out the window at a tree or a bird, or even just by watching TV or the Internet. The magnolia tree in our back yard, depicted above, produces a cloud of pink flowers for a week or so, but is now dropping its petals and replacing them with green foliage.

Tragically, the scourge of the coronavirus has taken many of our loved ones from us. Ironically, however, our inability to go anywhere we like has had perhaps a positive effect on the other scourge of our era, climate change. There is, at least temporarily, less pollution in our air, due to the lack of toxic emissions from cars and aircraft. (There is, however, a downside. It was reported that due to sanitary concerns, there was been an uptick in the use of non-reusable plastic.)

We must treat the Earth right, and she will treat us right, as expressed in this month's Quotations of the Month, the Homeric Hymn to Gaia and a short epigram from the so-called Homeric Epigrams.

A Hymn to Gaia

The Hymn to Gaia is one of the Homeric Hymns, a group of poems, in the same oral epic tradition as the Iliad and Odyssey, probably from the eighth century B.C. The longer Hymns are each about the length of one book of the major epics, and may have been meant for one evening's performance at dinner in some great house, although since they tend to end with a phrase like "Hail to you, goddess, and I will remember you in another song also," the bard may have intended an encore.

The longer Hymns are our sources for some important myths. The Hymn to Demeter tells of the kidnapping of Persephone by Hades, king of the Underworld, and how her mother, Demeter, goddess of the grain, searched for her, and having been reunited with her, founded the Eleusinian Mysteries. The Hymn to Apollo tells of Apollo's birth on Delos and his founding of his temple at Delphi. The Hymn to Hermes recounts the god's birth and how he invented the lyre from the shell of a tortoise, and gave the instrument to his half-brother, Apollo. The Hymn to Aphrodite is our source for the story of the goddess' love for the Trojan prince Anchises, and the birth of her son Aeneas, who was made famous in Vergil's Aeneid. Other Hymns are shorter, but tell stories, like the Hymns to Dionysos and Pan.

Many Hymns in the collection, however, are but short invocations of a divinity. There are thirty-three Hymns in all, the shortest only four or five lines long. The Hymn to Gaia, Mother Earth, is of medium length, at nineteen lines, praising the Earth for providing abundance to all, but with a word of warning, for, the poet says,

It is yours to give the means of life and to take it away from mortal men.

The poem ends with the usual formula

I will remember you and another song, also.but not before the poet has included his own personal request to the goddess for a successful career in exchange for his praise of her!

A warning epigram about Earth's moods

The second selection is a three-line invocation of the Earth goddess (here called Gê instead of Gaia) from the so-called Homeric Epigrams. These short musings were ascribed to Homer in antiquity, but who knows? The epigram selected here makes even more clear that Earth can act kindly toward those she likes, but can turn on those she is angry at. This is a message that we can take to heart. In these days when we repeatedly mistreat the Earth, we can expect her to turn on us, but if we treat her well, she will reward us.

Below, in Greek and English, are the two Quotations, Homeric Hymn XXX to Gaia and Homeric Epigram VII.

The Homeric Hymn to Gaia

A "Homeric Epigram" about Gaia

|

"Earth, Mother of All Things"I will sing of Gaia, mother of all, the well-rooted,she who is the oldest. She feeds all things that are upon the earth, those that walk upon the divine soil and those that go upon the sea and those that fly; all these are fed from her wealth. From you, Mistress, men become goodly in their children and in their harvest; it is yours to give the means of life and to take it away from mortal men. He is fortunate, whom in your heart you freely honor. He has everything in abundance, his life-bearing farmland is heavy with harvest, and in his fields he prospers in cattle, and his house is filled with fine things. Such men rule with good laws over their city of beautiful women and great wealth and riches accompany them. Their sons exult in youthful high spirits and their daughters disporting themselves in flower-bedecked dances skip with high-spirited hearts in the soft flowers of the meadow. Such are those whom you honor, majestic goddess, ungrudging spirit. Hail, mother of the gods, wife of starry Ouranos, freely grant me a heart-pleasing livelihood in exchange for this song. But I will remember you and another song, also. Earth knows her friends and enemiesLady Earth, all-bounteous, giver of honey-hearted wealth,indeed how plentiful you are for some persons, but you are difficult and harsh for those at whom you are angry. |

Gaia as giver of abundance and ferility. From R.H. Roscher, Ausfürliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1894-1890, Vol. I p.1583.

Quotation for March, 2020

The Athenian Acropolis

Precedents for the Coronavirus: The Plague at Athens, 430 B.C.: Thucydides Histories Book II |

Above: Pericles, 2nd Century A.D. Roman copy of a lost Greek original, the British Museum, photo by Brett Bigham, 2016, via Wikipedia.Top: The Athenian Acropolis, as it appeared in this detail of an antique postcard, collection of C.A. Sowa.

A long history of epidemics

We are in the midst of an epidemic (or pandemic, since it affects many different populations) of the disease known as the Coronavirus. Not only is the disease easily communicable and frequently deadly. The social and economic toll is equally deadly, with families separated and jobs and incomes gone. Health care workers are particularly at risk, since they are in constant contact with the sick, as are those incarcerated or otherwise forced to live in crowded circumstances.

The epidemic is described as "unprecedented," like nothing seen before. No one is sure how long it will last, or how to treat it. Some turn to religion or superstition — President Trump originally said that it would "miraculously" disappear, and some claim that religious medals will ward off infection. Conspiracy theories abound, claiming that the virus was manufactured in a laboratory by — take your pick — the Chinese or the Americans.

As a matter of fact, the experience is not without precedent. Often mentioned is the influenza epidemic of 1918, but even earlier, in the nineteenth century, waves of malaria and yellow fever devastated cities. Great numbers of people from rural areas were moving into cities, which had minimal infrastructure for handling sewage, which was usually dumped into the nearest river or bayou. In Memphis alone more than 5000 inhabitants perished in the yellow fever epidemic of 1878. The germ theory was a novel idea, questioned by many, and yellow fever was particularly mysterious, as the connection with mosquitos was still unknown. The French attempt to build the Panama Canal (later successfully completed by the U.S.) was thwarted not only by massive mismanagement but by devastating losses to the fever, only conquered at last by eradication of the mosquito. The most famous plague of course is the Black Death, the bubonic plague of the fourteenth century, which wiped out much of the population of Europe.

But long before any of these epidemics, there was the Great Plague at Athens in 430 B.C.

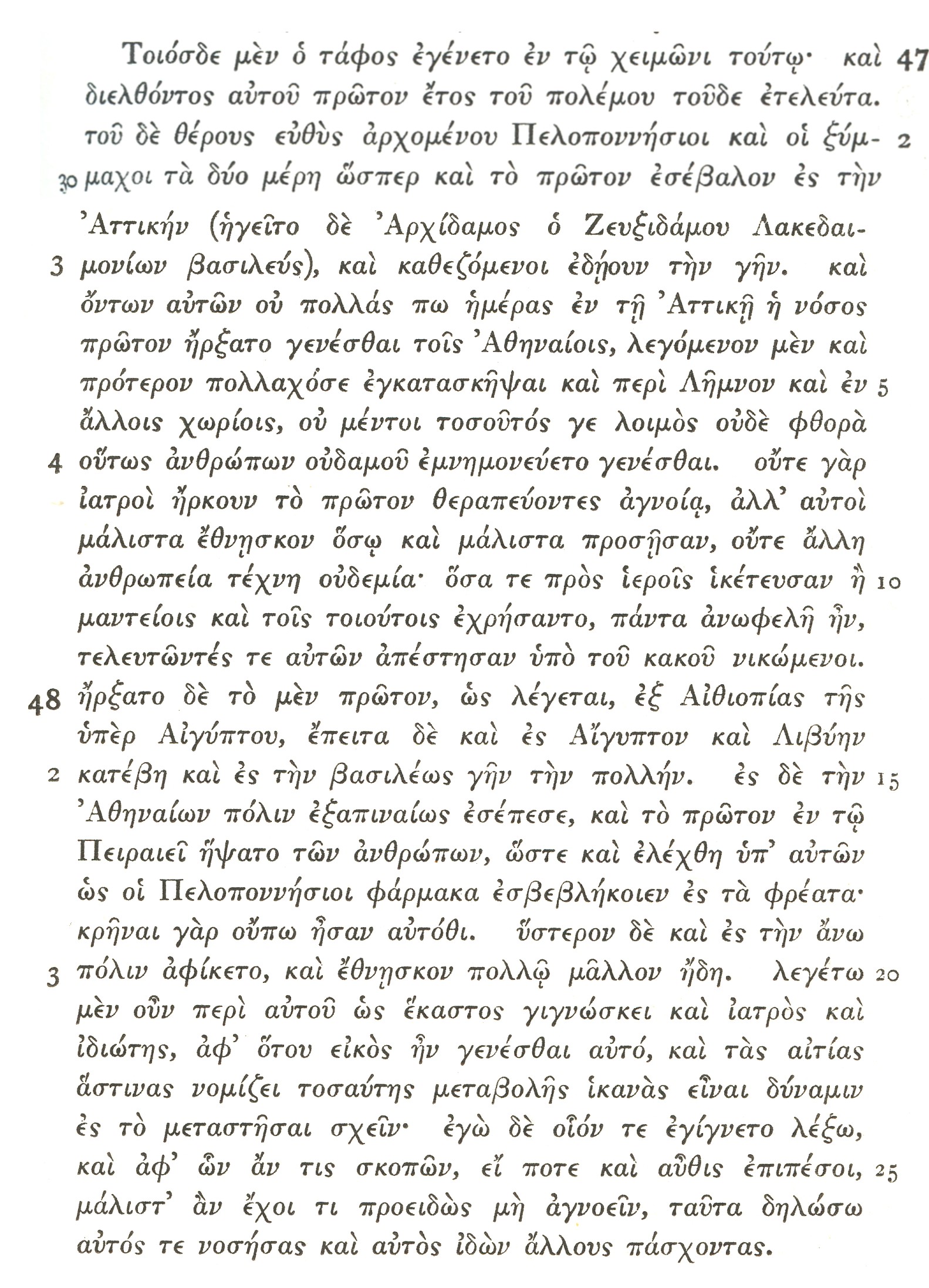

Thucydides describes the great plague at Athens

Thucydides (ca. 460 - ca. 400 B.C.) in Book 2 of his Histories describes the great plague that weakened Athens in the second year of the 27-year Peloponnesian War. The situation is eerily similar to that of the current epidemic, and a description of today's disaster could be ripped from the pages of the Greek historian.

As Thucydides describes the plague, it was unprecedented; no one could remember anything like it; no one knew what the cause was or how to treat it. Athens was overcrowded, as people from surrounding areas were crammed, by government policy, into the city. Physicians died in greatest numbers, since they were caring for the sick. People turned to religion or to divination, until they realized it was of no use. There were conspiracy theories, that the enemy had poisoned the waters. Thucydides himself became ill, and describes the course of the disease, in hopes that someone in the future will be able to recognize the disease, if it ever breaks out again.

The Peloponnesian War: the Peloponnesian League vs. the Delian League

The Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.) was fought between two major coalitions of Greek city-states. One group was made up of "the Lacedaemonians and their allies," often referred to as the Peloponnesian League. It was made up of Sparta and allied cities, mostly from the Peloponnese, including Corinth, whose strategic trade route on the isthmus joining the Aegean Sea and the Ionian Sea made that city a commercial rival of Athens. The other group was made up of Athens and her allies, which drew from members of the Delian League.

The Delian League was an organization of Greek states formed after the war with Persia and the defeat of Xerxes, in which Sparta had played a major role. Its purpose was to defend Greek interests against further incursions by the Persian king. Its headquarters and treasury were located on the holy island of Delos, which was most famous for the myth that it was the birthplace of Apollo and Artemis. Athens gradually took over as the leader of the alliance, and its treasury was moved to Athens. Members could either supply ships and men, or pay money. Most members chose to send money. Athens appropriated — we might say embezzled — most of the money for its own purposes, and the Delian League morphed into the Athenian Empire, with member states contributing the tribute that funded the Golden Age of Athens. Many of the monuments that we admire, including the Parthenon, were paid for by tribute money from Athens' client cities.

Pericles pens up the Athenians behind the Long Walls

Athens had, for a couple of hundred years, teetered between democracy and dictatorship (as described in the Quotation of the Month for February, 2020 "Impeachment and Ancient Athenian "Ostracism"). In the 5th century B.C., Pericles, who held the office of general, became the de facto ruler of Athens. As Thucydides puts it, Athens "became in name a democracy but in fact was the rule by its first man" ( hypo tou protou andros archê Thuc. II.65). Though from a noble family, Pericles was what we would call a populist, whose "base" was the working class, whose favor he won by such things as free theater tickets and lowering the property requirements for the important office of archon. In the Persian Wars he favored the navy over the land forces, partly because the sailors were largely drawn from the lower classes.

The first years of the war, known as the "Archidamian" War after the Spartan king Archidamus, consisted mainly of the Peloponnesians ravaging the orchards and farmlands around Athens, and the Athenians retaliating by sending their fleet around the Peloponnese and harassing the inhabiants. The political history of the time being murky and complicated, it is difficult to say what part Pericles played in stirring up hostilities, but his decision to crowd all the inhabitants of Attica behind its walls hastened not only the disaster of the plague but the eventual weakening of Athens itself.

Athens, in its inland position, had been connected to the port of Piraeus by fortifications known as the Long Walls (which can be seen in the map at the bottom of this item). Pericles somehow persuaded the rural inhabitants of Attica to abandon their farms and their livelihoods to cram into the space between these fortifications in the heat of summer, trusting to Athenian seapower to bring an end to the conflict. In these crowded conditions, the city, once the plague started, became, as we would say, a petri dish of contamination.

The symptoms of the disease, described by Thucydides

Thucydides, who suffered from the plague himself, describes in excruciating detail the symptoms of the disease. It started suddenly with a violent heat in the head and inflammation of the eyes, progressing down the body to a bloody throat, pain in the chest, upset stomach and nausea followed by violent spasms. The skin broke out in pustules. Internal heat caused people to throw themselves into cold water in a vain attempt to get cool. At this point many died, but in those that survived this initial attack, the disease continued down the body, attacking the private parts and the fingers and toes, and some became blind. Some of those who recovered suffered at first from loss of memory and "did not recognize themselves or their friends."

It is still not known what disease caused the plague. Some have speculated that it was typhoid. At least one third of the population of Athens (about 30,000 victims) perished.

Death of Pericles and military collapse of Athens

Pericles himself died of the plague, and Athenian politics, which had always been chaotic, became even more so. Leaders came and went. A disastrous attack on Syracuse, in Sicily, destroyed Athens' sea power. An oligarchy briefly took over. Aristophanes' comedy, Lysistrata, in which women go on strike, refusing to have sex until the men end the war, was produced in 411 B.C., expressing the people's frustration with the continued fighting.

Athens eventually lost the war to Sparta, but power went back and forth between the Greek cities. Thebes, the great seven-gated city famous for Cadmus, Oedipus, and Dionysus, was the leader for a while. Even the Persians got in on the act, mostly backing the Peloponnesians. Finally, in the 4th century B.C., Philip of Macedon and his son Alexander ("the Great"), who had studied with Aristotle, swept down and took over all of Greece, and beyond. The Peloponnesian War was a conflict involving the entire Greek world, and could be called the World War of its era.

Athens was no longer a military power, but continued to be an intellectual center of learning and philosophy, long into Roman times.

Below, in Greek and English, is the beginning of Thucydides' description of the plague. The funeral mentioned in the first line of the quotation is the funeral for the Athenian war dead in the first year of the war, at which Pericles delivered his electrifying Funeral Oration, in which (in words perhaps enhanced in Thucydides' telling) he describes Athens as she would like to see herself, as a land of opportunity and "the school of Hellas."

Thucydides Histories II.47-48

|

No one knew where the plague came from or what to doThus the funeral took place that winter. And with its completion the first year of the war ended. As soon as summer began, the Peloponnesians and their allies, with two thirds of their force, as they did the first time, invaded Attica (led by Archidamus, son of Zeuxidamus, king of the Lacedaemonians), encamped and laid waste the land. After they had been in Attica not many days, the plague began to appear among the Athenians, it being said that it had broken out previously in many places, around Lemonos and in other towns, but such pestilence and mortality was nowhere remembered to have taken place. Nor could the physicians help at first, giving treatment in ignorance, but they themselves died in greatest number, as they visited the sick most often, nor was any human skill of help. As often as people prayed in the temples or made use of divination and such things, all these activities were useless, and finally people ceased from them, overwhelmed by this evil. It first began, it is said, in Ethiopia above Egypt, and crossed into Egypt and Libya and most of the king's country. It fell suddenly upon the city of Athens, first attacking the people of Piraeus, so that it was claimed by them that the Peloponnesians had put poison in the cisterns, for there were as yet no wells there. Afterwards it arrived in the upper city, and many more died. About its origins each person, whether physician or layperson, will have an opinion, as it seems to him, whatever causes he thinks would be able to produce such a disturbance of nature. As for me, I shall tell what it was like, and I will describe the symptoms by which the observer, if it should strike again, can, by knowing them beforehand, recognize it, since I myself was sick with the plague and saw others suffering from it . . . |

A map showing the Long Walls of Athens and the wall connecting Athens with the old port at Phaleron. Map Athene in de Oudheid (in Dutch) by Napoleon Vier, via Wikipedia.

Quotation for February, 2020

Cleisthenes of Athens

Impeachment and Ancient Athenian "Ostracism:" Plutarch Life of Aristides |

_Stoa_of_Attalus_Museum.jpg)

Above: An ostrakon bearing the name of Aristides, on display in the Ancient Agora Museum in Athens, housed in the Stoa of Attalus. photo by Giovanni Dall'Orto, November 9, 2009, via Wikipedia.Top: Modern bust of Cleisthenes, "Father of Athenian Democracy," at the Ohio Statehouse, Columbus, Ohio. (Attribution: http://www.ohiochannel.org", via Wikimedia.)

Impeachment in America and ostracism in Athens

Impeachment in the U.S is the process of bringing an a accusation against a public official with the goal of removing the official from office. The Constitution provides that the House of Representatives can bring a bill of impeachment against the President of the U.S. for treason, bribery, or "high crimes and misdemeanors," the latter phrase being the subject of heated disagreements. Impeachment is, however, only the accusation; the Senate then votes on whether to remove a duly elected President from office. We have just seen a bill of impeachment brought against President Donald Trump in the the majority Democratic House, but he was acquitted in the heavily Republican Senate. Impeachment is in the Constitution, but stands outside of the regular process of election.

Ancient Athens had a similar process of removal of a public figure that was outside of the normal electoral process. It was called ostracism.

We use the term ostracism today to mean simply a shunning of an individual by any group. In ancient Athens, however, it had a specific legal meaning. Citizens literally wrote the name of the person they wanted to remove on an ostrakon, a broken piece of pottery, or potsherd, and dropped it into an urn in a designated part of the agora, or main square. The person whose name got the most votes was exiled from Athens for ten years, but was allowed to keep his property and the income from it. Citizens included only free men; women and slaves could not vote. A vote of ostracism could be called only once a year, and only one person could ostracized in that year. The reason for ostracizing an individual was not generally the commission of a specific crime, but simply that the person had become too powerful, and was therefore considered a threat to democracy. Sometimes the reason seems to have been largely political rivalry. According to Plutarch, if the total number of votes was less than 6000, the ostracism was void for that year.

According to Aristotle's Constitution of Athens (Athenaion Politeia) the procedure of ostracism was instituted by Cleisthenes, the lawgiver who gave Athenian democracy its historic form, often called the "Father of Athenian Democracy."

Draco, Solon, and Cleisthenes as lawgivers of Athens

Draco (Drakon) gave Athens its first written constitution (621 B.C.), replacing the old unwritten laws and blood feud. His laws, called thesmoi, were posted on wooden tablets where everyone could see them. Draco's laws had a reputation for harshness; death was the punishment for many crimes, including the stealing of a cabbage (however, fragmentary evidence seems to show that there was a distinction between voluntary homicide, punishable by death, and involuntary homicide, or manslaughter, punishable by exile). From this harsh reputation we get the word "draconian."

Solon (ca. 630 - ca.560 B.C.) repealed most of Draco's laws and reorganized the Athenian government. Solon, too, gave us a common English word, "solon," meaning "a wise lawgiver." However, his reforms were not enough to prevent the populist leader Peisistratus from seizing power and ruling Athens as "tyrant" (i.e dictator), followed by his sons Hipparchus and Hippias. These three ruled for over thirty years (546-510 B.C.).

After the Peisistratids were driven out with the help of the Spartans, and after a period of upheaval, our third lawgiver, Cleisthenes, took over leadership and gave form to what we think of as Athenian democracy. Perhaps most importantly, he redefined tribal affiliation. Instead of belonging to a tribe based on hereditary family ties, one's tribal identity was based on one's deme, or neighborhood of residence. Athens was divided into three regions, the city (asty), the coast (paralia), and the inland region (mesogeia). Each tribe consisted of three demes, one from each region, breaking up the old feudal power structure. (It is as if an American voting unit were made up of one precinct from New York, one from California, and one from Iowa.) Cleisthenes was said to have also introduced the procedure of ostracism.

Pre-written ostraka for the illiterate

If the voter was illiterate, he could ask someone else to fill out his "ballot" by inscribing a name on a potsherd for him. Thousands of marked ostraka have been found by archaeologists, with different names on them, showing the popularity of the process. One cache of 190 ostraka all bearing the name of "Themistocles" were found dumped in a well near the Acropolis, written in fourteen different handwritings. Were these prepared as an ancient example of ballot-box stuffing? Or were they simply prepared by campaign workers ready to "help out" those unable to write?

The first known ostracism was in 487 B.C., of Hipparchus, son of Charmos, a relative of the tyrant Peisistratus. The last was in 416 B.C., of Hyperbolus, son of Antiphanes. After this, the question of whether to hold an ostracism was put to the Assembly each year, but none was called for. In 471, the great Themistocles, hero of the Second Persian War, who rebuilt the Athenian navy that defeated the Persians at the Battle of Salamis (480 B.C.), was ousted by political enemies and ostracized. He went into exile and ended up at the Persian court. He was made governor of Magnesia (in present-day Turkey), where he died in 459 B.C. of natural causes. In 482, Aristides, called "The Just" (Dikaios), was ostracized, but was recalled from exile in 480 to serve as a general in the war against Persia. He was a political rival of Themistocles, and unlike Themistocles, he believed not in naval power but in the primacy of land forces. Yet he served honorably at Salamis with Themistocles, who himself would later be ostracized.

Why the Athenian wanted Aristides "The Just" ostracized

Plutarch, in his Life of Aristides, tells a funny story about the ostracism of Aristides. An illiterate man, not recognizing the great general, asked Aristides to write the name "Aristides" on the ostrakon he was about to deposit in the urn. Aristides asked the man what ill "Aristides" had done him. "None at all," said the man, "I'm simply annoyed at hearing him called 'The Just' all the time." Never letting on who he was, Aristides politely wrote his own name on the ostrakon and gave it to the man.

Below, in Greek and English, is Plutarch's anecdote about the Athenian who asked Aristides to write his own name on the ostrakon. Plutarch says that Aristides then said a prayer that was "the opposite of the one offered by Achilles." Achilles' prayer was for revenge against his fellow Greeks.

Plutarch Aristides VII.5-6

|

He simply got tired of hearing Aristides called "The Just!"This was what was done, to speak in general outline: Each man would take an ostrakon and write on it the name of whatever citizen he wanted to remove, then take it to a place in the agora all fenced about with railings. Then the archons first counted the entire number of ostraka. If the voters were less than six thousand, the ostracism was void. Then separating each name separately, the one whose name was written by the most they banished by proclamation for ten years, but allowing him the profits from his property. At that time, as voters were writing on their ostraka, it is said that an illiterate and entirely rustic man handed his ostrakon to Aristides, thinking he was just one of those who happened to be there, and asked him to write "Aristides" on it. Aristides asked him in wonderment if "Aristides" had done him some wrong. "None at all," he said, "I don't even know the man, but it annoys me to hear him everywhere called 'The Just'." Hearing this, Aristides said nothing in reply, but wrote his name on the ostrakon and gave it back. Finally, as he was leaving the city, stretching his hands towards the heaven he uttered a prayer, the opposite, it seems, to that of Achilles, that no crisis would overtake the Athenians that would force the people to remember Aristides. |

A view of Athens, looking toward the Acropolis, on an antique postcard, collection of C.A. Sowa.

Quotation for January, 2020

Our Hero!

For the Lunar Year of the Rat: The Pseudo-Homeric Battle of the Frogs and Mice |

Above: A dapper Frog and Rat, of unknown provenance (from Gerald Quinn, The Clip Art Book, 1990).Top: A rat emoji (Apple version).

The Lunar Year of the Rat

It is the time of the Chinese New Year, and in the Lunar Calendar, the year 2020 is a Year of the Rat. The Rat, and persons born in a Year of the Rat, are said to be intelligent, diligent, creative, and adaptable. They have a keen sense of intuition (observe that rats are said to leave a sinking ship, or a mineshaft that is about to collapse). Different Years of the Rat are associated with different ones of the five elements — Metal (gold), Earth, Water, Wood, or Fire. The year 2020 is a year of the Metal Rat.

Rats and mice in ancient Greece and Rome

Rats and mice are thought to have originated in Asia. It is not known when these rodents were first introduced to Greece and Rome. It is quite likely that their introduction owes something to the vast trade routes that crisscrossed the Asiatic and Mediterranean lands. They would have enjoyed in particular the contents of the great grain fleets of the Romans. In both Latin and Greek, the words mus and mys could refer either to a mouse or rat, or one of several other rodent-like types of animal. (In Chinese, also, the word shu can mean "rat," "mouse," or other such animal). Like the rat, the mouse is also diligent, adaptable, and cozy with the human environment.

Our Quotation of the Month is from mock epic in Greek of unknown authorship and date called the Batrachomyomachia, or Battle of the Frogs and Mice, in which an unlucky mouse (or is it a rat?), although belonging to a species known for its ability to survive, drowns when it falls off the back of a frog that promised him a ride across the pond, but suddenly dives into the water.

The Batrachomyomachia, or Battle of the Frogs and Mice

The Batrachomyomachia has been variously credited to Homer (as the Romans believed), or to Pigres of Halicarnassus, brother of Artemisia, Queen of Caria and an ally of Xerxes (according to Plutarch). Others ascribe the poem to an anonymous poet of the time of Alexander the Great.

In the poem, a mouse, named Crumb-snatcher (Psicharpax) is drinking water from a lake when he encounters a frog named Puff-jaw (Physignathos) swimming across the lake. They fall to comparing genealogies, as well as diets. The mouse prefers such things as bread, honey cakes, cheese, or slices of ham and liver. He is not interested in cabbages and other vegetarian food, such as the frog might like. The frog is not interested in the mouse's food talk, but offers him a ride across the lake to visit the frog's own house. The mouse accepts, riding on the swimming frog's back. All goes well at first, but the mouse begins to regret his decision as waves arise and the land recedes. Suddenly a water snake appears, and the frog, without thinking of the consequences for the mouse, dives. The poor mouse, flailing about, screams and squeaks, but eventually drowns, not before calling for revenge from the Mouse Army (Myôn stratô).

Another mouse observes all this, and the mice declare war on all the frogs. Puff-jaw lies, saying that he had nothing to do with the problem. A tiny Homeric battle ensues, with both sides arming themselves with armor from the natural world, such as greaves made of bean pods, spears made from rushes, and cabbage-leaf shields. Zeus decides to intervene, asking Athena to help the mice. She refuses, complaining that mice are eating the garlands and lamp oil from her temple, and have even chewed holes in her sacred robe. She won't help the frogs, either, because they keep her awake at night with their croaking. The battle rages, going back and forth, and finally the mice are winning. Zeus takes pity on the frogs, and sends an army of crabs, who nip at the tails and paws of the mice. The mice at last retreat, and the war is over.

Below, in Greek and English, is the section where the unhappy mouse, thoughtlessly dumped in the lake by the diving frog, drowns, and, as he flails about, calls for vengeance upon the frogs from his fellow mice. The pancration ("all strengths"), at which the mouse claims to excel, was a combination of boxing and wrestling.

Batrachomymachia vv.56-98

|