These are quotations for the year 2015. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2015, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2015 |

Below are quotations for the year 2015. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2015

Click on a link to read each quotation

2015

- December, 2015: For the Holiday Season: Apollo Receives the Lyre from Hermes (Homeric Hymn to Hermes 475-502).

- November, 2015: For the Election Debates: The Muses Can be Liars, or They Can Tell the Truth (Hesiod, Theogony 1-34).

- October, 2015: For Halloween: Is a little bat the ghost of a Mycenaean king? (Iliad Book II and George Seferis, "The King of Asine").

- September, 2015: For the autumnal equinox: The timely revolution of the seasons (Lucretius De Rerum Natura 159-191.

- August, 2015: Summer spiders and Penelope's web (Odyssey I and II).

- July, 2015: A trip to the vet evokes the shape-shifting god Proteus (Odyssey IV).

- June, 2015: In honor of the Triple Crown winner American Pharoah: Alexander the Great, Horse Whisperer (Plutarch, Alexander VI.3-5).

- May, 2015: For Mother's Day: the child that is a little bit different can be a challenge (Homeric Hymn XIX to Pan)

- April, 2015: For the beginning of spring, Proserpina returns to her mother Ceres (Ovid, Fasti and Metamorphoses).

- March, 2015: An Etruscan haruspex warns Julius Caesar to beware the Ides of March (Suetonius, The Divine Caesar).

- February, 2015: Valentine's Day in the Lunar Year of the Goat or Sheep (Longus, Daphnis and Chloe).

- January, 2015: Boreas, the North Wind, can sometimes be useful (Herodotus VII.189).

Quotation for December, 2015

For the Holiday Season: Apollo Receives the Lyre from Hermes (Homeric Hymn to Hermes 475-502) |

Apollo with the lyre. Early Attic vase (from Roscher's Lexikon, 1894).

A time of year for festivals

December is the time for festivals: Christmas, New Year's Eve, Hanukkah, and Kwanzaa. There was the Roman Saturnalia, and, oldest of all, the Winter Solstice, when the Sun, having withdrawn its life-giving light, pauses to ponder its next move and reverses course in a return to its proper place in the sky.

Music is part of the celebration. Appropriately, Beethoven's birthday is on December 16.

How Apollo, god of music, got his lyre

Apollo is the deity most closely associated with music; he was leader of the Muses. Apollo had many other functions, too. He was a god of prophecy and oracles, especially at Delphi. He was a god of medicine (Asclepius was his son); he brought both healing and plague. In later mythology, he was identified with Helios, the Sun (and his sister Artemis became identified with Selene, the Moon). Like Helios, Apollo possessed a herd of sacred cattle, and they provide the rationale behind the aetiological myth of How Apollo Got His Lyre.

Hermes invents the lyre and steals Apollo's cattle

In Homeric Hymn IV to Hermes, the infant trickster god Hermes, at noon on the day of his birth, finds a tortoise, and promising to "make her a sweet singer," hollows out her shell and, fitting it with ox horns, hide, and sheep-gut strings, creates the world's first lyre. Later that day, he steals fifty head of cattle from Apollo's herd and drives them off, driving them backwards to confuse detection and wearing funny wicker shoes to disguise his own footprints. Eventually, Apollo discovers the theft and deduces that the thief is his half-brother Hermes (Zeus is father of both). Apollo is, after all, the god of divination.

After first pleading ignorance (I'm just a baby! How could I do that?), Hermes, hauled off before Zeus, is forced to return the cattle. He plays his new lyre for Apollo to put him in a good mood. Apollo is enchanted, and Hermes offers him the lyre as a peace offering, explaining that it must be played correctly or else it will just make a lot of noise. Apollo, of course, plays it beautifully, and makes Hermes a god of cattle herders.

Hermes has one last trick, however. Deprived of the lyre, he invents the Pan-pipe, the instrument of herdsmen.

Below, in Greek and English, are the verses in which Hermes gives the lyre to Apollo, who tries it out.

Homeric Hymn IV.475-502

|

Hermes gives the lyre to Apollo

". . . but since your heart is strongly eager to play the lyre, |

Sundial at Sailors' Snug Harbor, Staten Island, New York. Photos by C.A. Sowa. At the Winter Solstice, the Sun seems to reverse course in the sky.

Quotation for November, 2015

For the Election Debates: The Muses Can be Liars, or They Can Tell the Truth (Hesiod, Theogony 1-34) |

Maidens dancing. Untermyer Fountain, Central Park, New York City, sculpture by Walter Schott, ca. 1910 (photo by C.A. Sowa). I have long used this photo elsewhere on this web page, illustrating the traditional theme of "Maidens Dancing and Picking Flowers," one of the traditional scenes analyzed in my Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns published by Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Mundelein, IL, 1984. It is a theme employed by Hesiod in the Prologue to his Theogony.

The tall tales of politicians

Narrative is important in establishing a public identity. Nowhere is this more true than when the teller is running for office. This is a particularly silly season of presidential debates and campaign rhetoric, in which it can be difficult to tell truth from fiction in the Stygian tide of tales and counter-tales that wash over us.

On the Democratic side, was Hillary Clinton really hiding something in the e-mails that she kept on her private server? It has already been shown that her story of dodging sniper fire in Bosnia in 1996 was totally fictitious. Among the Republicans, Ben Carson's claim to have turned down a "full scholarship" to West Point could not be true, as tuition to the military academy is always free. And his lurid tales of a violent youth in Detroit are remembered by no one who knew him. Likewise, recollections by (King of the Whoppers) Donald Trump to have seen "thousands of New Jersey Muslims" cheering as the World Trade Center was destroyed have been corroborated by no actual eyewitnesses.

In a previous election (the Quotation of the Month for August 2012), we invoked the philosopher Diogenes, who is famous for "living in a barrel" and "going around with a lantern looking for an honest man." Diogenes was a serious philosopher (a rival of Plato), who also delighted in silly publicity stunts. But his camping out in a "barrel" (actually a large pithos or clay storage container) and his "lantern" act are the narratives that define his identity. This season, however, we introduce another model of story-telling, the Muses that Hesiod met at the foot of Mount Helicon, who inspire narratives both false and true.

The Muses dance and sing on Mount Helicon

The Prologue to Hesiod's Theogony, his tale of the generations of the gods and monsters, is a hymn to the Muses who inspire him. They dance and sing on Mount Helicon in Boeotia, and the scene is instantly recognizable as a type scene of ancient oral epic that I call, in my Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns, "Maidens Dancing and Picking Flowers." They may dance, sing, bathe in a fountain, or otherwise disport themselves.

Often a threatening male character intrudes. Persephone and her friends were picking flowers when Hades kidnapped her. Nausicaa and her handmaidens were playing ball on the seashore when Odysseus emerged from the water, naked and shipwrecked. In the Theogony, it is the Muses who come down from the mountain and accost Hesiod, as he minds his sheep.

Hesiod meets the Muses, and learns to tell stories

The Muses, first insulting all shepherds for being lazy good-for-nothings, teach Hesiod to sing, giving him a laurel staff as his insignia. But they also caution him that they they know how to "tell many lies that resemble the truth," but "when they want, they can also speak the truth." (So we ask, did Hesiod really see the Muses, or is that another tall tale?)

Below, in Greek and English, is the Prologue to Hesiod's Theogony, with the description of his meeting with the Muses. The Greek verses about falsehood and truth are outlined in red. In English, the verses are in boldface.

Hesiod,Theogony 1-34

|

Hesiod meets the Muses on HeliconWith the Heliconian Muses let us begin our song, |

The Mantineian Reliefs (ca. 350-320 B.C.), showing six of the nine Muses. (National Museum of Athens.)These were discovered in 1887 by M.G. Fougère of the French School at Athens, in a ruined Byzantine church at Mantineia in Arcadia, used upside down as paving stones. A third relief represented Apollo and Marsyas, the satyr flayed alive by Apollo for daring to challenge him in music. A missing slab may have depicted the remaining three Muses. These marbles belong to the Praxitelean school of sculpture, and some have speculated that they are the pieces described by Pausanias (VIII.9) as forming the bases of statues by Praxiteles.

The illustrations above are from Roscher's Lexikon of 1894-1897, adapted from the illustrations in Fougère's original article in the Bulletin de correspondence hellénique of 1888.

Quotation for October, 2015

For Halloween: Is a little bat the ghost of a Mycenaean king? (Iliad Book II and George Seferis, "The King of Asine") |

Hellenistic fortifications (ca. 300 B.C.) surrounding the Mycenaean city of Asine. Photo by Heinz Schmitz, from Wikipedia.

A mysterious ancient fortress

The ruins of the ancient Mycenaean city of Asine sit perched on a spit of land overlooking the east side of the Argolic Gulf, in the northern part of the Peloponnese. Homer mentions Asine only once. The tantalizing reference appears in the Catalog of the Ships in Iliad II, a listing of all the separate contingents that sailed for Troy, with the leaders of each and the number of ships they contributed. Overall, they were led by King Agamemnon of Mycenae. The great hero Diomedes led ships from cities dominated by the stronghold of Argos. The cities, in addition to Argos, were Tiryns, Hermione, Asine, Troezen, Eïonae, Epidaurus, Aegina, and Mases. Asine appears only as "...and Asine..." (Asinên te).

Asine's long history begins in the Neolithic period and continues on into the Bronze Age and beyond. Following the downfall of the Mycenaean civilization, habitation continued into the Iron Age. Around 700 B.C., Argos destroyed Asine in revenge because Asine helped Sparta in its war with Argos, and its inhabitants were resettled in another part of the Peloponnese. Even then, some inhabitants stayed, and in the Hellenistic period around 300 B.C. Asine was recolonized, and the present fortifications were built, and in late Roman times baths were erected there. During Turkish rule, the fortifications were added to, and during World War II, Italian forces occupied the site. The place is today known as "Kastraki" ("little fort"), and nearby is the town of Tolo. The closest city is the seaport of Nafplio, capital of the Argolid region of modern Greece.

Modern excavations

In 1920, Swedish archaeologists began excavations at Asine at the instigation of Crown Prince Gustav Adolf, and excavation continued up to the beginning of World War II. In 1970, however, excavation was resumed, and continued until 1990. At present, no field work is being done, and Asine is once again neglected, except for campers and those enjoying the nearby beaches. Some of the pottery found by the Swedish archaeologists is now in the Asine Collection at the University of Uppsala, and other artifacts are on display in the museum in Nafplio. The well-known terracotta mask known as the "Lord of Asine" (see illustration below) is from a late period, and is probably not a king at all, but perhaps a mask of a goddess, used in some ritual.

Searching for an elusive past

The modern Greek poet George Seferis (Giorgios Seferiades) wrote "The King of Asine" (O basilias tês Asinês) in 1940, after a visit to the recently excavated site. There, he was inspired by by his own desire to recapture an elusive yet somehow living past, both of the ancient city and his own.

Seferis (1900-1971) won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1963. He was born near Smyrna, in present-day Turkey, a city that his family was forced to leave after the exchange of minority populations between Greece and Turkey in 1922. He would not see Smyrna again until 1950, and a sense of exile and a desire to reconnect with his own Greek past haunts his poetry. In "The King of Asine," Seferis goes around all sides of the citadel, both its dark side and its sunlit side, searching for the elusive King and those who once lived there. The only clue in Homer is the mysterious Asinên te... "and Asine..." He imagines a gold death mask, like the one found by Schliemann at Mycenae, but beneath the mask he finds only an emptiness (ena keno). He finds in himself, too, only emptiness.

Could a little bat be the King of Asine?

In the final stanza of the poem, a bat suddenly flies out of the dark and "strikes the light of the sun as an arrow strikes a shield." Could this be the "King of Asine" for whom he has been searching?

In her article "George Seferis and Homer's Light," written for the Center for Hellenic Studies, Jennifer Kellogg shows how Seferis was affected by Homer's use of the phrase "the light of the sun" (phaos Êelioio) as a way to indicate life, as opposed to the darkness of death. In his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize, he described his feelings toward this phrase. Perhaps this little bat, emerging from the dark to connect with the sunlight, is the connection the poet has been seeking.

Below, in ancient Greek, modern Greek, and English, are verses from Homer's Catalog and Seferis' vision.

Homer,Iliad II.559-568

George Seferis, Basilias tes Asines

|

Diomedes led the contingent from Argos and surroundings (-Homer)They that held Argos and Tiryns of the high walls, All morning we looked round and round the citadel. . . |

The so-called "Lord of Asine," in the Archaeological Museum at Nafplio (via site www.argolis.de).

Quotation for September, 2015

For the autumnal equinox: The timely revolution of the seasons (Lucretius De Rerum Natura 159-191) |

Treading grapes for wine. Rome, 2nd half of 1st century A.D. Ancient Roman reliefs in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow. Photo by Shakko, 2009, via Wikipedia.

The timely seasons prove that nothing can come from nothing

We have just passed the autumnal equinox, when we slide from the brutal heat of summer into the nostalgic plateau of fall. This year we had the additional excitement of a total lunar eclipse, which was more spectacular because it occurred during a so-called "supermoon," when the moon is closest to the earth, appearing at its largest and brightest. (Some, of course, saw in this a portent of some apocalyptic happening.)

This month our Quotation of the Month comes from Lucretius (c. 99 B.C. - c. 55 B.C.), who saw in the reasonable ordering of the seasons and the orderly growth of each species from its own seed a proof that the world could not have been created out of nothing by some capricious god. For, he reasoned, if something can be created from nothing, then anything can be created from anything. Human life could originate in the sea and fish be born on land. Things would require no time to grow; babies would suddenly become adults and crops would appear out of nowhere and at the wrong time. The result would be disorder. Obviously, people, animals, and plants are born from their own seeds, derive appropriate nourishment, and grow on their own timetable.

Philosophy versus religion in Lucretius

Lucretius hated organized religion. In Book I of De Rerum Natura ("On the Nature of Things") he recounts in painful detail the killing of Iphigeneia by her father Agamemnon as an offering to the gods, as they pray for a fair wind on the expedition to Troy. Lucretius follows the version in which Iphigeneia is duped into thinking that she is to be married to Achilles, only gradually learning that she is to be sacrificed. Lucretius reacts in horror: "Such evils could religion prompt" (Tantum religio potuit suadere malorum!).

Lucretius followed the philosophy of Epicurus (341 - 270 B.C.), who, adapting ideas from Democritus (c. 460 - c. 370 B.C.), was an early adherent of the atomic theory. The world, according to the Epicureans, was composed of atoms, which were constantly recycled to create everything that exists. The Epicureans believed that the gods exist and are immortal, but that they do not concern themselves with the world or with human beings. They have no interest in punishing people in this life or the next, and people should get over their fear of divine punishment. In Book I, Lucretius lays out the basic principles of Epicurean science and cosmology, which he eleborates in the following five books.

Below, in Latin and English, is Lucretius' description of his version of the Origin of Species.

De Rerum Natura 159-191

|

Everything in its season and in its proper way

For if they came from nothing, then from all things Furthermore, why do we see the rose in spring, the grain in summer warmth, It is obvious that none of these events happen, since all things |

Enjoying the fruits of the vintage. Kalyx crater (mixing bowl), Greek, Apulia (Italy), 375/350 B.C. A reclining god Dionysos holds a cup of wine, as a woman plays the harp. Behind her, another woman holds an incense burner and a thyrsos, or ritual staff. On the right is a nude satyr. Art Institute of Chicago, photo by C. Sowa, March, 2015.

Quotation for August, 2015

Summer spiders and Penelope's web (Odyssey I and II) |

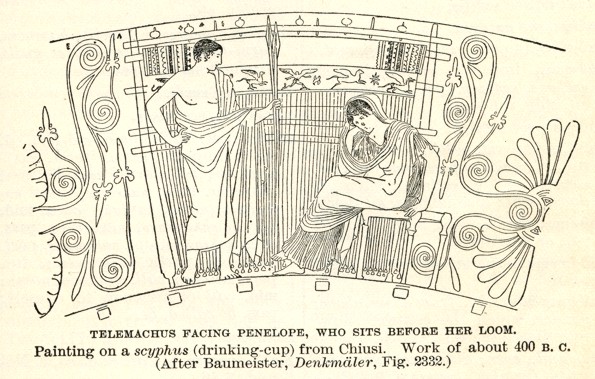

Telemachus stands before Penelope, who sits at her loom. Image from Allen Rogers Benner, Selections from Homer's Iliad, with an Introduction, Notes, a Short Homeric Grammar, and a Vocabulary, 1906. Above, a spider on my living room window (with a pine branch behind her).

Penelope in my garden

August is the month for garden spiders. In the evening I watch these deft ladies create their big cartwheels, stretched between the side of the house and a nearby tree, or between two tomato bushes. Tentatively and cautiously at first, a big spider I was observing swung her line from the wind chimes over to the azalea, then to a dogwood tree, which she ran up, trailing her line behind her. Stretching the thread taut she ran back and forth across it, strengthening it with more silk. Once the horizontal support was ready, she worked quickly, making vertical supports upon which she built her concentric web. Then she sat in the middle of her circle of doom, waiting for whatever flew into it. By morning the web was gone, consumed by the spider, and that night she wove it again.

The obvious reference is to Arachne, the eponymous weaver who gave spiders the name of arachnid. There are various versions, but in all of them, she challenges the goddess Athena to a weaving contest, arrogantly refusing to give credit to the goddess for the gift of her craft. For, as is said in the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite (Hymn V vv. 12-15):

[Athena] first taught earth-dwelling men to be builders,

making carriages and chariots, cleverly decorated, of bronze;

she taught splendid crafts to tender maidens in their houses,

putting ideas into the mind of each girl.

Hesiod tells us in his Works and Days (v. 63-64) that:

[Zeus ordered] Athena to

teach [Pandora] crafts, how to weave at the clever loom.

In revenge, Athena turns Arachne into a spider.

But I am reminded more of the story of Penelope. She, too, created a new web each day, then destroyed it, to begin again the following day.

Penelope conflicted over her future

Penelope is portrayed as the faithful wife, waiting twenty years for the return of Odysseus, while fending off the advances of the evil Suitors. The story is, however, more complicated than that. There are signs in the Odyssey that despite her grief, she gave serious thought to remarrying, and was somewhat conflicted about the decision — as was her son Telemachus. In Odyssey 1.249-250, Telemachus complains to "Mentes" (actually Athena in disguise) that his mother "neither rejects marriage nor brings the matter to a conclusion."

The problem is not just that the Suitors are eating Penelope and Telemachus out of house and home, partying, drinking, singing and dancing, and playing dice. ("What kind of feast is this?" asks Mentes. "This obviously isn't a meal where everyone brings his own food (éranos)" (Od. 1.226).) More importantly, they are breaking the rules of courtship. If they really want to marry Penelope, they should go to her father Icarius and formally ask for his daughter's hand in marriage (Od. 2.50-58). Mentes advises Telemachus that if his father is dead, he should find a husband for his mother — then kill the Suitors (Od.1.289-196). Obviously the husband should not be one of them! As we see, Penelope herself has a say in the matter, too.

Penelope's most famous delaying tactic is the never-finished robe, which for three years she weaves on her great loom every day, only to tear it apart at night. She claims that she is weaving a shroud for Odysseus' father Laertes, who is approaching the end of his life. Eventually, one of her maids tells on her, and the Suitors force her to finish her web. Antinous, one of the Suitors, provides a self-serving explanation to Telemachus, that the situation is not really their fault, but Penelope's, for leading them on, "making promises to each man and sending them messages."

Below, in Greek and English, is Antinous' aggrieved description of Penelope's ruse.

Odyssey 2.87-110

|

Penelope's deception

". . . The Achaean suitors are not to blame, |

Bell krater in the manner of the Niobid Painter, Athens, ca. 450 B.C. (Art Institute of Chicago). A warrior hands his helmet to a woman wearing a diadem. He is thought to be returning from war. (Photo by C.A. Sowa, March, 2015.) Just so, Penelope hopes for Odysseus' return.

Quotation for July, 2015

A trip to the vet evokes the shape-shifting god Proteus (Odyssey IV) |

Unwilling to be caged, Guy Noir shows his wild side

My big black cat Guy Noir recently had to go to the veterinarian for his checkup and regular rabies shot. Guy was a stray cat that I adopted seven years ago off my back porch, where I was feeding him. He was then about two years old, and consistently showed signs of battle. One day, I lured him into the kitchen, slammed the door behind him, and after some exhausting warfare, got him to the vet, where he literally tried to climb the walls. The doctor gave him antibiotics for his wounds and I had him neutered. Seven years later, living indoors, he has mellowed. But when I try to put him in his carrier, all his feral instincts against entrapment come rushing back.

Eleven pounds of so-called housecat become three-hundred pounds of writhing, wrestling jaguar, powerful jaws open to expose fangs that seem to grow enormously in size. I put on a leather jacket and work gloves to deal with this fellow. With his powerful muscles, he repeatedly flowed from my arms and disappeared under the furniture, to reappear, Cheshire cat-like, in a totally different room. Finally, with the aid of some veterinary sedative, I grabbed him by the tail and dropped him unceremoniously into the carrier. Guy was fine at the vet, and now that he is home, he is in his usual position sprawled on the floor, letting me walk over him, or else curled up with his best friend, playful Cleopatra.

I thought of nothing so much as the myth of Proteus, the shape-shifting Old Man of the Sea, and Menelaos' attempts to wrestle him into submission.

Proteus and Menelaos

The story of Proteus is well known. We even have an adjective, "Protean," meaning something that constantly changes shape, so that we can't get a handle on it. In the fourth book of the Odyssey, Telemachos, searching for his father Odysseus, who has been missing for twenty years, is at the court of King Menelaos in Sparta. Menelaos has long been back from Troy, happily reunited with his wife Helen, whose escapade with Paris was the whole cause of the war. He entertains the young prince with tales of his own adventures.

Menelaos' ship was becalmed on Pharos, off the coast of Egypt, because he has not offered the required hecatombs to the gods. The sea goddess Eidothea, Proteus' daughter, tells him how to lie in wait for her father and capture him, wrestling with him in many guises, until he resumes his proper shape and prophesies his future to him. Proteus, shepherd of the seals, emerges at midday with his well-fed flock to take a nap. Menelaos and three companions must lie on the beach covered in seal skins, pretending to be seals. So much seal really stinks, so Eidotheia puts ambrosia in their nostrils to kill the smell. Menelaos and his companions grab Proteus, who turns successively into a lion, a snake, a leopard, and a huge boar, He becomes a river of flowing water (think of Guy Noir flowing out of my arms!) and finally a lofty tree. Eventually, Proteus wearies and returns to his normal shape. Answering Menelaos' questions, he explains the gods' wrath at him, and tells of the fates of the other heroes of Troy, including Odysseus, who is imprisoned on Calypso's island. Menelaos himself, when his life is over, will be transported to the Elysian Fields to live in eternal comfort, because he is married to divine Helen, Zeus's daughter.

Myths of experience

These myths were composed by rural people, who would have been experienced in wrangling cantankerous animals!

Below, in Greek and English, is the scene of Menelaos' wrestling with the many-formed Proteus.

Odyssey 4.447-463

|

Wrestling the Old Man of the Sea

The entire morning we waited with patient hearts. |

Quotation for June, 2015

In honor of the Triple Crown winner American Pharoah: Alexander the Great, Horse Whisperer |

Alexander and Bucephalus in combat at the battle of Issus, portrayed in the Alexander Mosaic, Naples, National Archaeological Museum. Uploaded to Wikipedia by Berthold Werner. Above, detail of chariot of Helios, metope from Temple of Athena, Troy, after 390 B.C., now in Berlin, Altes Museum. image from Roscher's Lexicon, 1890.

American Pharoah wins the Triple Crown

He did it! American Pharoah, with his oddly spelled name, became the 2015 winner of the Triple Crown of Thoroughbred horse racing, prevailing in the iconic Kentucky Derby, the Preakness, and the arduous mile-and-a-half-long Belmont Stakes. He joins an elite group of only twelve horses, going back to Sir Barton in 1919, who have achieved this feat, which requires not only speed but endurance and a great heart. And of course, a great jockey, in this case, Victor Espinoza, and his winning trainer, Bob Baffert. Previous Triple Crown winners include, among others, the legendary mounts Citation (1948), Secretariat (1973), Seattle Slew (1977), and Affirmed (1978), who was the last to win this distinction until this year. Affirmed's victories were unique in that in each race, the same horse, Alydar, was always his rival and close second.

This month, we honor another great-hearted horse, Bucephalus ("Ox Head"), Alexander the Great's celebrated war horse.

Famous horses of antiquity

Perhaps the most famous horses of antiquity are the Trojan Horse, in which Odysseus and his men smuggled themselves into Troy, and the winged horse Pegasus, tamed by Bellerophon. But whatever reality lies behind these narratives, the land of reality and the mists of myth are inextricably intertwined. But Bucephalus was a real horse, although as usual, some aspects of his story have undoubtedly been embroidered.

Alexander and Bucephalus

Bucephalus, described as huge and black, with a white star on his forehead, was Alexander's comrade and mount in many battles across Asia. At the age of thirty, he died, after the battle of the Hydaspes, in modern Pakistan, perhaps from wounds suffered in that battle. Alexander buried Bucephalus near the site, and founded a city named after him, Bucephala, identified as modern-day Jhelum.Plutarch tells of how Alexander's father, the Macedonian king Philip, was offered the horse by a Thessalian horse dealer. Philip refused to buy him, as he seemed totally wild and incapable of being tamed. Teenage Alexander, however, saw something in the horse (perhaps a kindred spirit?), a move that worried his father. Did Alexander really think he knew more about horses than his elders? But Alexander quickly saw how to control the spirited animal. Seeing that the horse was spooked by his own shadow, he turned him to face the sun, and took off his trailing cloak, which was a distraction. Stroking his huge new friend, who was eager to run, he mounted him and rode around the course at full gallop. Whether true or not, the story goes that Philip predicted that his son would find Macedonia too small for him, and must "find a kingdom equal to, i.e. worthy of, himself."

Below, in Greek and English, is the story of Alexander's taming of Bucephalus.

Plutarch, Alexander VI.3-5

|

Alexander, Horse Whisperer. . . [Alexander said] "This horse, at least, I could manage better than another man." [Philip said] "And if you don't succeed, what penalty will you pay?" "I shall," he said, "pay back the price of the horse." Laughter broke out, then an agreement was made about the money. Alexander immediately ran to the horse, and seizing the reins, turned the horse toward the sun, for, as it seemed, he had noticed that it was disturbed at seeing its shadow falling in front of it and bouncing about. Little by little in this way, running beside the horse and stroking it, as he saw that it was full of courage and spirit, he quietly cast aside his cloak, sprang up and easily bestrode it. Then with a slight pressure of the reins on the bit, he controlled the horse without striking it or tearing its mouth. When he saw that the horse free of the fear that threatened it, but eager to run, he let it go at full speed, inciting it with a bolder voice and urging it with his heel. Among Philip and his retinue there was at first anxiety and silence. But when Alexander made the turn correctly and came back proud and rejoicing, all the others broke into shouting, but it is said that his father cried tears of joy, and when Alexander dismounted he kissed his head, saying, "O my son, look for a kingdom equal to yourself, Macedonia does not have room enough for you." |

Pegasus and Bellerophon. Image from Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.

Quotation for May, 2015

For Mother's Day: the child that is a little bit different can be a challenge (Homeric Hymn XIX to Pan) |

"The Piper at the Gates of Dawn." Rat and Mole meet Pan. Illustration by Paul Bransom for Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows, 1913.

The weird child

Every parent expects the newborn child to be "perfect." The son or daughter who is autistic, or exhibits a physical disability, or some oddity of appearance or behavior, can present a challenge to the best of parents. Mother and father can only do what we all should do with every being with whom we come in contact, that is to recognize in her or him those individual qualities that can surprise us with their ability to bring great joy.

This month's Quotation of the Month, from Homeric Hymn XIX to Pan, tells of the birth of such an infant, a child of total weirdness, born with a goat's feet and face, complete with horns and beard. At first a figure of fear with his cacophonous laughter, he becomes a source of delight.

Pan as benign spirit

We often think of Pan as a benign figure, a harmless woodland deity. Herodotus tells the legend of the runner Pheidippides meeting Pan in Arcadia as he ran to Sparta to ask the Spartans to aid the Athenians in the war against the Persians. (Pheidippides is often confused with the unnamed courier who brought news of the victory at Marathon to Athens. The confusion is caused by a sentimental Victorian poem by Robert Browning which conflated the two. And neither of them dropped dead!) In another modern fantasy, Kenneth Grahame's 1913 novel of animal friendship The Wind in the Willows (illustrated above), Mole and Rat search for Portly, the baby otter who has wandered off, leaving his father Otter sick with worry. They have a mystical encounter with Pan, discovered playing his pipes with the baby otter sleeping peacefully between his hooves. The vision melts away, and so does the song, like a dream that one struggles to recall on waking, remembering only its sweet feeling. Portly, suddenly bereft of his divine rescuer, awakens, but is comforted by Mole and Rat who return the baby otter to his grateful father.

The wild god Pan

Pan was, however, essentially a wild forest spirit of fertility, particularly associated with the mountain backwoods of Arcadia. He hunts wild animals and is often found in the company of nymphs, with whom he sings, plays on his pipes, and dances. He likes noise (philokroton) and can get very angry and cause panic (Panikon deima, "Panic terror"). In Theocritus' First Idyll, the shepherd Thyrsis asks the goatherd to play a tune on his Pan-pipes, but the goatherd refuses, for it is noontime, when Pan takes his nap, and he will be angry if he is awakened.

It is not allowed, O shepherd, it is not allowed at noontime

to play the pipes. We fear Pan. For at that time he rests,

weary, from hunting. He is mean,

and bitter anger sits always in his nostrils.

Pan is a god of sexual prowess, often represented with an erect phallus. An elaborate statue found in the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum depicts him having sex with a blissful-looking goat.

Pan's mother is unnerved, but his father is delighted

In the Homeric Hymn, the nymphs sing of Pan's birth. His parents are the god Hermes and a nymph, daughter of Dryops. The name "Dryops" means "Oak-visaged," indicating a tree-spirit. The infant "looks like a monstrosity" (teratôpon), with his horns, beard, and goat's feet and his noisy behavior. A hasty dropping of the child and a running out of the room ensues. (It is not certain who drops him. There is disagreement over whether tithênê has its usual meaning "nurse" or whether it means "mother." I translate as "she who nursed him.") Father Hermes, a trickster god himself, who played practical jokes the day he was born (Homeric Hymn IV), saves the situation by taking the child, wrapped in rabbit skins, to show him off to the other gods, who all are charmed and delighted by the wild infant. The poet follows the folk-etymology of "Pan" as meaning "all." The name is more likely derived from the word meaning "to pasture" flocks.

Below, in Greek and English, is the story of Pan's birth.

Homeric Hymn XIX to Pan vv. 27-47

|

Hermes saves the situation[The nymphs] sing of the blessed gods and lofty Olympus. |

"The Great God Pan." Wood carving by my mother, Christine Cooper Angier (1930's).

Quotation for April, 2015

For the beginning of spring, Proserpina returns to her mother Ceres (Ovid, Fasti and Metamorphoses) |

Knob-handled patera, or libation dish, Greek, from Apulia, Italy, 330-320 B.C. Attributed to the Baltimore Painter. Hermes leads Demeter and Persephone from the Underworld. Art Institute of Chicago, photo by C.A. Sowa, March, 2015. The crocuses above are from my garden.

Proserpina's return brings resurgence of spring vegetation

The games in honor of Ceres, goddess of the grain, Ovid tells us in his month-by-month calendar Fasti, were held on the 12th of April. This gives Ovid an excuse to tell the story of Ceres, (Greek Demeter) and her daughter Proserpina (Greek Persephone; Ovid uses both forms, depending on the meter), abducted by the Underworld god Dis (Pluto, Greek Hades). The story of the maiden's abduction and return symbolizes and mythically explains the return of vegetation and crops in spring after a long, hard winter.

Ovid's Fasti: The poet puts his whimsical stamp on the story

The primary source for the story of Persephone is the Homeric Hymn II to Demeter (ca. 750 B.C.). Ovid, in Book 4 of the Fasti (8 A.D.), includes all the main points of the story: Proserpina, picking crocuses and other flowers with her companions, is abducted by the Lord of the Underworld (who is her uncle). Ceres wanders far and wide looking for her, as the crops dry up and die. During her travels she disguises herself as an old woman and becomes nursemaid to a child (Demophon in the Hymn, Triptolemus in Ovid), whom she tries to make immortal by putting him in the fire. She is interrupted by the child's mother, Metanira, so that a successful future, but not immortality, awaits him. Proserpina is returned to Ceres, but because she ate one or more pomegranate seeds, she can only leave the Underworld for part of the year, remaining underground for the other part. Nothing is said in Ovid of the founding of Demeter's temple or her Mysteries, a central point of the Hymn.

Ovid being Ovid, he introduces whimsical elements into his narrative: Arethusa, the Sicilian fountain nymph, invited all the matron goddesses to a banquet, preventing Ceres from keeping proper guard over her playful daughter. Ceres almost found Proserpina on the first day by following her footprints, but some wandering hogs obliterated the trail!

Ovid's Metamorphoses: A variation with characters transformed into other things

Ovid also told the story in his Metamorphoses (Book V), but since that voluminous work is all about transformations, the emphasis is on characters who are changed into other things. The story is sung by the Muse Calliope in a singing contest, whose origins are too lengthy to tell here. As she tells it, Venus encourages Cupid to shoot his arrow into the King of the Underworld, causing him to fall in love with Proserpina (another complicated story). The innocent girl is carried off while picking flowers, as usual. But a Sicilian water nymph, Cyane, in a blow for women's rights, stands up to Pluto, telling him he should have wooed Proserpina, not abducted her, and puts out her arms to block him. Pluto strikes her pool with his sceptre and opens the earth to receive him and the abducted girl. Cyane melts away in tears and becomes one with her pool of water.

The pomegranate seeds make their mandatory appearance, but instead of Pluto forcing her to eat them, as in the Hymn, Proserpina, wandering innocently in a garden of fruit trees, plucks the pomegranate and eats some seeds. In another Ovidian innovation, Ascalaphus, son of the nymph Orphne and the infernal river Acheron, sees her eat the seeds and tattles on her, with the implication that if no one had seen her, she could have enjoyed a permanant return to the world above! Proserpina, no longer the innocent girl but the powerful Queen of the Underworld, turns Ascalaphus into an ill-omened owl, whose dire appearance foretells death and doom.

Ascalaphus' punishment as an ill-omened owl

Below, in Latin and English, is the story of Ascalaphus' betrayal of Proserpina.

OvidMetamorphoses V.533-550 Dixerat, at Cereri certum est educere natam;non ita fata sinunt, quoniam ieiunia virgo solverat et, cultis dum simplex errat in hortis puniceum curva decerpserat arbore pomum sumptaque pallenti septem de cortice grana presserat ore suo, solusque ex omnibus illud Ascalaphus vidit, quem quondam dicitur Orphne inter Avernales haud ignotissima nymphas ex Acheronte suo silvis peperisse sub atris; vidit et indicio reditum crudelis ademit. ingemuit regina Erebi testemque profanam fecit avem sparsumque caput Phlegethontide lympha in rostrum et plumas et grandia lumina vertit. ille sibi ablatus fulvis amicitur in alis. inque caput crescit longosque reflectitur ungues vixque movet natas per inertia bracchia pennas foedaque fit volucris, venturi nuntia luctus, ignavus bubo, dirum mortalibus omen. |

Ascalaphus tattles on Proserpina

He spoke, but Ceres was resolved to bring her daughter back. |

Sarcophagus, depicting the abduction of Persephone. Roman, ca. 190-200 A.D. Art Institute of Chicago, photo by C.A. Sowa, March, 2015.

Quotation for March, 2015

The Etruscan connection: A haruspex warns Julius Caesar to beware the Ides of March (Suetonius, The Divine Caesar) |

Figurine of a haruspex, from the right bank of the Tiber 4th cent. BC. Full cast bronze. Height cm 17.7. Vatican Museums, Gregorian Etruscan Museum online, cat. 12040cat. 12040. A haruspex was an Etruscan seer who divined the future from the entrails of sacrificed animals. A model sheep's liver, with incised guide marks, is illustrated at the end of this article. It was a haruspex named Spurinna who told Caesar to beware danger not later than the Ides of March.

A Caesar for all seasons

Julius Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March, March 15, 44 B.C. His death, following his own gradual amassing of absolute powers, was followed by the accession to power of his grand-nephew and heir, Octavian (as the emperor Augustus), ending the Roman Republic and signaling the beginning of the Roman Empire. The meaning of Caesar's death has been the subject of many interpretations, which have changed many times in tune with the times in which it has been interpreted. Was Caesar a ruthless dictator with monarchical ambitions, and Brutus a republican hero for killing him, or was Caesar a populist hero, against whom Brutus committed an act of personal betrayal? Or was Caesar a talented military tactician, to be studied for his artfulness in war? Shortly after the assassination, Brutus had silver denarii minted bearing his own portrait, implying perhaps his own desire to be king.

In the English-speaking world, students have traditionally learned of Caesar from two sources, his own writings (chiefly his de Bello Gallico, a model of lucid Latin) and Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. Interpretations of Caesar and Brutus have shifted, while culture and politics changed, as analyzed by Maria Wyke in Caesar in the USA (2012). During the Revolution, for example, Caesar was equated with the hated British King Geroge III, but when Lincoln was assassinated, many felt that "a mad Brutus had felled a mighty leader." Many mood swings later, Caesar was linked with Mussolini and even Hitler.

Plutarch vs. Suetonius

The two main Classical sources for the life of Caesar are Plutarch's Parallel Lives and Suetonius's Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Shakespeare took his play mostly from Plutarch, with changes for dramatic effect. He compresses, for example, two Battles of Philippi into a single battle, and has Caesar assassinated in the Capitol instead of the actual venue, the Curia Pompeii. Plutarch (ca.46-120) and Suetonius (ca.69-after 122) were almost exact contemporaries, both born long after the events they describe. But Plutarch was Greek, from Chaeronea in Boeotia, and was a priest of Apollo at Delphi, and although he became a Roman citizen, remained mostly in Chaeronea and wrote in Greek. Suetonius was from Italy and was a friend of the senator and writer Pliny the Younger. In describing the assassination of Caesar, both mention mostly the same incidents: there were portents foretelling the murder, Caesar's wife Calpurnia suffered nightmares, and both tell how at the funeral an innocent man named Cinna was torn to pieces by the crowd, who thought he was the conspirator Cinna. And both include a seer who warns Caesar against the Ides of March, and when Caesar mocks him by saying that the Ides have come with no ill effect, says, "they have come, but they have not gone." Caesar's Comet, which blazed in the sky for seven days, was discussed in the Quotation for November, 2014.

Suetonius' Etruscan specifics

Portents are something a writer can have fun with, the more spectacular the better, and here the authors diverge, with Plutarch (followed by Shakespeare) being more generically macabre, and Suetonius more locally Italian. Shakespeare has Calpurnia report "most horrid sights seen by the watch":

A lioness hath whelped in the streets;In addition, men on fire walk the streets, and a sacrificial victim was found to lack a heart. Plutarch, too, has nocturnal crashing sounds, lights in the sky, birds of omen, men all on fire and the victim without a heart.

And graves have yawn'd, and yielded up their dead;

Fierce fiery warriors fought upon the clouds,

In ranks and squadrons and right form of war,

Which drizzled blood upon the Capitol;

The noise of battle hurtled in the air,

Horses did neigh, and dying men did groan,

And ghosts did shriek and squeal about the streets.

Suetonius, however, is the most interesting, because his portents are strictly local. Roman colonists sent to Capua, an ancient Italian city originally settled by the Etruscans, had discovered what was said to be the tomb of Capys, father of Anchises, whose son Aeneas, along with his mother Venus, were considered to be Caesar's ancestors. A tablet was found within the tomb foretelling the death of a descendant of Capys at the hands of his kinsmen. Then the horses released by Caesar as a dedication to the river Rubicon after his crossing refused to graze and "wept copiously." A little king-bird (avem regaliolum) flying into the Hall of Pompey (where Caesar would be assassinated) bearing a sprig of laurel was torn to pieces by other birds, and Caesar himself dreamt that he flew above the clouds and clasped the hand of Jupiter.

In Suetonius, Caesar is warned about the Ides of March not by Shakespeare's random demented "soothsayer" or Plutarch's generic mantis, but by a haruspex, a respected Etruscan priest who divined the will of the gods by examining the liver of sacrificed animals. The haruspex wore a pointed headdress of hide or felt, tied under the chin to keep it from falling off (a bad omen), as depicted in the figurine pictured above. A model liver, with marked divisions, like the one pictured below, could be used as a guide. Caesar's haruspex bears the Etruscan name "Spurinna."

Below, in Latin and English, is Suetonius' enumeration of the portents surrounding Caesar's assassination.

SuetoniusDivus Julius 81 Sed Caesari futura caedes evidentibus prodigiis denuntiata est. Paucos ante menses, cum in colonia Capua deducti lege Iulia coloni ad exstruendas villas vetustissima sepulcra disicerent idque eo studiosius facerent, quod aliquantum vasculorum operis antiqui scrutantes reperiebant, tabula aenea in monimento, in quo dicebatur Capys conditor Capuae sepultus, inventa est conscripta litteris verbisque Graecis hac sententia: "Quandoque ossa Capyis detecta essent, fore ut illo prognatus manu consanguineorum necaretur magnisque mox Italiae cladibus vindicaretur." Cuius rei, ne quis fabulosam aut commenticiam putet, auctor est Cornelius Balbus, familiarissimus Caesaris. Proximis diebus equorum greges, quos in traiciendo Rubiconi flumini consecrarat ac vagos et sine custode dimiserat, comperit pertinacissime pabulo abstinere ubertimque flere. Et immolantem haruspex Spurinna monuit, caveret periculum, quod non ultra Martias Idus proferretur. Pridie autem easdem Idus avem regaliolum cum laureo ramulo Pompeianae curiae se inferentem volucres varii generis ex proximo nemore persecutae ibidem discerpserunt. Ea vero nocte, cui inluxit dies caedis, et ipse sibi visus est per quietem interdum supra nubes volitare, alias cum Iove dextram iungere; et Calpurnia uxor imaginata est conlabi fastigium domus maritumque in gremio suo confodi; ac subito cubiculi fores sponte patuerunt. |

A catalog of Etruscan portentsBut his future murder was announced to Caesar by clear portents. A few months before, when the colonists brought to the colony at Capua under the Julian Law to construct country villas were demolishing some very ancient tombs, and were doing so more eagerly because as they searched around they found a considerable number of small vases of antique workmanship, they came upon a bronze tablet in a tomb, in which Capys, founder of Capua, was said to be buried. On it, in Greek characters and Greek words, was inscribed this sentiment: "Whenever the bones of Capys shall be discovered, a descendant of his will be slain at the hands of his kindred, and will be avenged with great destruction to Italy." For this matter, lest anyone think it a fable or a falsehood, the authority is Cornelius Balbus, a very close friend of Caesar. In the preceding days, Caesar learned that the herds of horses, which, when he crossed the Rubicon, he dedicated to the river and let wander without a keeper, stubbornly abstained from their feed and wept copiously. And when he was offering sacrifice, the haruspex Spurinna warned him to beware of danger which would appear not later than the Ides of March. The day before that same Ides, a little king-bird, flying into the Hall of Pompey with a sprig of laurel, was pursued by birds of various kinds from the neighboring grove, which tore it to pieces in that same place. That very night, upon which arose the day of his murder, he himself seemed in his dream one moment to fly above the clouds, at another to clasp hands with Jupiter, and his wife Calpurnia thought that the gable of the house had collapsed and that her husband was stabbed in her arms; then suddenly the doors of the bedroom flew open of their own accord. |

A model liver as a guide for divination. Bronze diagram of a sheep's liver found at Picenum with Etruscan inscriptions. Bronze Liver of Piacenza, photo uploaded to Wikipedia by LoKiLeCh.

Quotation for February, 2015

VALENTINE'S DAY IN THE LUNAR YEAR OF THE GOAT OR SHEEP (Longus, DAPHNIS AND CHLOE) |

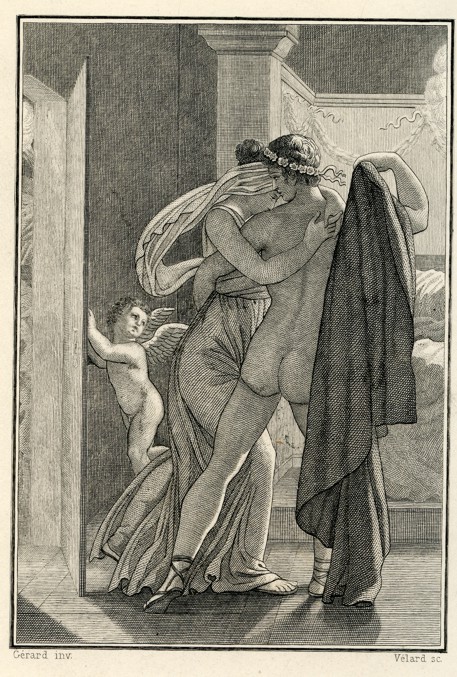

Daphnis and Chloe together at last. Illustration by Gérard from the Vizetelly edition, ca. 1890, originally in the "Amyot edition" published in French by Pierre Didot in 1800. The little engraving of doves in the header, also from the Vizetelly edition, was designed by the Regent, Philip of Orleans for an edition that he sponsored in 1718.

A pastoral coming-of-age romance

February is a month of hope. It brings us Valentine's Day, and spring is less than a month away, even if the Polar Vortex is still bringing us Alps of snow. 2015 is the Lunar Year of the Goat, or is is it the Sheep? Even the Chinese aren't sure; the words are the same, with only an added qualifier to tell the difference. This month's Quotation brings these themes together, in an excerpt from one of the world's oldest romantic potboilers, Daphnis and Chloe by Longus, who probably wrote in the second or perhaps third century A.D., and who, despite his Latin name, wrote in Greek. He may have been from Mitylene on the isle of Lesbos, since that is where the story is set, a tale of beautiful young people, sheep, and goats.

From rustic innocence to love and wealth

In the story, the infant Daphnis is discovered by a goatherd, being suckled by one of his she-goats, which has deserted her own kid to care for the infant child. Inexplicably, the child is wearing rich clothing. Later, the baby Chloe, also richly clothed, is found by a shepherd in a grotto of the Nymphs, being suckled by a ewe. The herdsmen and their wives raise the children as their own. Daphnis and Chloe grow up together, pasturing the landowner's herds, and cavort together naked, bathing in the grotto of the Nymphs. In fact, they cavort a lot. They begin to develop strange feelings which, in their innocence, they cannot identify.

Chloe is wooed unsuccessfully by Dorcon, another herdsman, who gives her a magic pipe. Pirates carry off Daphnis and some cows he is tending, but Chloe saves him by blowing the pipe to summon the cows, which leap overboard, upsetting the boat. Daphnis and the cows swim to shore, but the pirates drown. A wise old retired herdsman, Philetas, who now tends his garden, informs Daphnis and Chloe that what they feel is Love. Philetas tells a charming story of meeting the god Eros, who appears as a mysterious little boy playing in his garden, then reveals his true nature and flies off as a winged sprite. Philetas tells Daphnis and Chloe to kiss and hug a lot. They take his advice, but still feel something is missing. Chloe, too, is kidnapped, but is rescued by the god Pan.

Daphnis encounters Lycaenium, a married woman from the city, who initiates him into the Joy of Sex, which is described in graphic detail. (It seems that his knowledge of animal breeding wasn't entirely transferable — the technique is a bit different. At this point, some English translators, like the Vizetelly edition of 1890, use language which it describes as "considerably chastened," or, as in the case of the 1916 translation by George Thornley, display amnesia of their native language and lapse into Latin.) Lycaenium advises Daphnis not to try his new knowledge on Chloe, "because she will scream loudly and bleed a lot as if being murdered." Daphnis also has an unwelcome suitor in the person of the parasite (i.e. hanger-on) Gnatho, a drunkard who seeks to obtain him from his master for sexual purposes. Daphnis starchily lectures Gnatho (displaying his knowledge of animal biology), that "he-goats mount she-goats, not other he-goats, rams mount ewes, not other rams, and cocks mount hens, not other cocks." (Here, too, Thornley lapses into Latin.)

Finally, Daphnis is revealed to be the son of Dionysophanes, the landowner for whom he works, and Chloe is found to be the daughter of the wealthy Megacles. Everyone celebrates, they get married, and Daphnis finally initiates Chloe into the Art of Love. They decide to remain in the country, and determine that when they have a son, he will be suckled by a goat, and their daughter will be suckled by a sheep.

Daphnis and Chloe's influence

Jacques Amyot published a French translation of Daphnis and Chloe in 1559, and the story helped spark the fashion for pastoral fiction in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It influenced many subsequent novels, such as Paul et Virginie by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (1788). Offenbach wrote an operetta on the subject, Ravel wrote a ballet for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, and the story continues to inspire imitators. All the illustrations on this page are from the edition published by Vizetelly & Co., ca. 1890, with small decorations designed by the Regent, Philip of Orleans for an edition which he caused to be issued in 1718, and large engravings executed by Prudhon and Gérard for the "Amyot edition" published by Pierre Didot in 1800.

Philetas finds Eros flitting about his garden

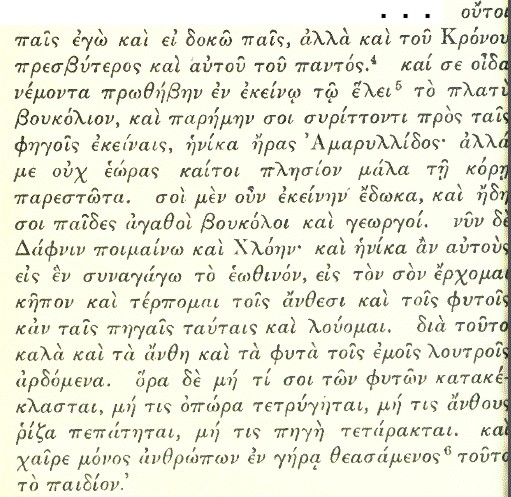

Below, in Greek and English, from Philetas' encounter with the winged god of Love, is the boyish-looking divinity's description of himself, "invisible, but older than Kronos and all the Universe."

LongusDaphnis and Chloe II.5

|

|

Eros is older than the Universe, but forever young". . . I am not a child, even if I look like a child, but am older than Kronos and the Universe itself. I knew you when you were in the prime of youth, pasturing your great herd in yonder marshy meadow, and I was with you when you played your Pan-pipes under those oak trees, for love of Amaryllis. But you didn't see me, although I stood very near the girl. I gave her to you, and as a result I gave you as sons some excellent herdsmen and farmers. Now Daphnis and Chloe are the objects of my shepherding. And when I have brought them together early in the morning, I come to your garden and amuse myself with your flowers and plants and I bathe in these fountains. That is why the flowers and plants are beautiful, because they are irrigated with my wash-water. Look, if any of your plants have been broken, if any fruit has been pulled off, if the root of any flower has been damaged, if any spring has been polluted. And rejoice that you alone of all mortals in your old age have seen this little boy." |

The infant Daphnis suckled by a goat. Illustration by Prudhon from the Vizetelly edition, ca. 1890, originally in the "Amyot edition" published in French by Pierre Didot in 1800.

Quotation for January, 2015

Boreas, the fierce North Wind, can sometimes be useful (Herodotus VII.189). |

Boreas, the North Wind, from the frieze of the Tower of the Winds, Athens. (Image by way of Wikipedia.)

Boreas bears down on us

The Polar Vortex is upon us again, with Boreas, the North Wind and his brothers bringing us snow and sleet in their fierce rage. As Hesiod tells us in his Works and Days, winter is the time for man, woman, and beast to hunker down as the storm blows and "earth and woods howl" (W&D 508). But sometimes the wind gods are helpful, especially when they fall on one's enemies. Our Quotation of the Month tells of one such episode, when prayers to Boreas helped the Athenians against the Persians.

Boreas destroys the Persian fleet at anchor

In July, 480 B.C., Xerxes was on his way down the Greek coast, having crossed the Hellespont. It was to be only a short time before the battle of Thermopylae, famous for the last stand of Leonidas and his gallant Spartans. Xerxes' vast fleet, meanwhile, was anchored off the coast of Magnesia, in northern Greece, too numerous to seek safe harbor close to land. A huge storm arose, destroying many of the Persian ships. The Greeks, meanwhile, were anchored farther south, off Euboea. The Greeks, according to Herodotus, ascribed the Persian catastrophe to the intervention of Boreas, god of the North Wind. Since Boreas' wife was Oreithyia, daughter of Athenian King Erechtheus (whom Boreas had kidnapped in one of those usual great-god-rapes-young-virgin myths), the Athenians considered him a family member who would help them. He had, they believed, helped them previously when the fleet of King Darius, Xerxes' father, had been wrecked in a storm in 490 B.C. off Mount Athos. Xerxes avoided a repeat of that disaster by cutting a canal through the Athos peninsula. Of course, as we now know, the entire Persian fleet would eventually be defeated in September, 480 in the great sea battle of Salamis.

Below, in Greek and English, is Herodotus' description of the Greeks' gratitude to Boreas and Oreithyia.

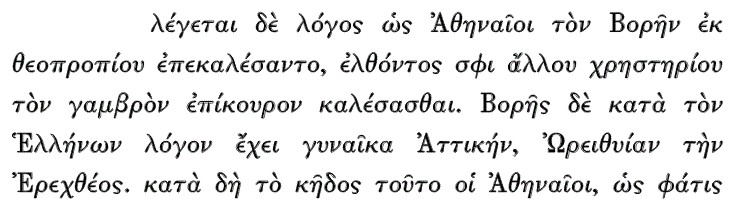

Herodotus VII.189

|

|

Prayers to Boreas fulfilledThe story is told that the Athenians summoned Boreas because of a prophecy, having received another oracle that they should call upon their son-in-law for aid. Boreas, according to the Greek story, had an Attic wife, Oreithyia daughter of [King] Erechtheus. By this marriage connection, the Athenians, so the rumor goes on, figured that Boreas was their son-in-law, and as they lay at anchor at Euboean Chalkis, when they saw that a storm was rising, or even before, they sacrificed both to Boreas and to Oreithyia, and called on them to exact vengeance and destroy the ships of the barbarians, as they did before off Mount Athos. Whether it was because of this that Boreas fell upon the barbarians as they lay at anchor, I cannot say. But the Athenians say that Boreas both then and previously brought these things to pass, and on their return home they founded a temple to Boreas by the river Ilissus. |

Boreas carries off Oreithyia. (Image from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.)

<---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2014 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: